The History of Sir Charles Grandison

The book was a response to Henry Fielding's The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, which parodied the morals presented in Richardson's previous novels.

[2]: 140–2 Richardson hesitated to begin such a project, and he did not work on it until he was prompted the next year (June 1750) by Anne Donnellan and Miss Sutton, who were "both very intimate with one Clarissa Harlowe: and both extremely earnest with him to give them a good man".

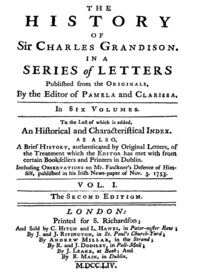

Immediately following the firing, Richardson wrote to Lady Bradshaigh, 19 October 1753: "the Want of the same Ornaments, or Initial Letters [factotums], in each Vol.

[2]: 146 The novel begins with the character of Harriet Byron leaving the house of her uncle, George Selby, to visit Mr. and Mrs. Reeves, her cousins, in London.

However, he is stopped at Hounslow Heath, where Charles Grandison hears Byron's pleas for help and immediately attacks Pollexfen.

After explaining why obedience to God and society are important, Grandison wins Pollexfen over and obtains his apology to Byron for his actions.

However, a new suitor, the Earl of D, appears, and it emerges that Grandison promised himself to an Italian woman, Signorina Clementina della Porretta.

As Grandison explains, he was in Italy years before and rescued Jeronymo, son of the Marchese della Porretta and a relationship developed between himself and Clementina, the marquess's only daughter.

Shortly after their marriage, they receive news from the Poretta family that Clementina has fled Italy to avoid their further pressuring her to marry the Count of Belvedere, one of her suitors.

Sir Charles negotiates a reconciliation on the terms that the family will leave it up to Clementina, without further pressure or urging, whether she will marry on the condition that she will abandon her plans to join a nunnery.

Sir Charles vivacious sister Charlotte's marriage has improved because she is showing her husband more respect and is excelling in her role as a mother, something she had originally dreaded.

The Poretta family returns to Italy with Clementina saying she will take a year to collect her thoughts and then will decide whether to marry the Count of Belvedere.

The novel ends with the death of Sir Hargrave Pollexfen, who dies miserably of wounds he suffered while behaving with iniquity toward another woman.

In a "Concluding Note" to Grandison, Richardson writes: "It has been said, in behalf of many modern fictitious pieces, in which authors have given success (and happiness, as it is called) to their heroes of vicious if not profligate characters, that they have exhibited Human Nature as it is.

[6] This sharing of personal feelings transforms the individual responders into a chorus that praises the actions of Grandison, Harriet, and Clementina.

[5]: 47 Flynn claims that Grandison is filled with sexual passions that never come to light, and he represents a perfect moral character in regards to respecting others.

[5]: 261–2 In terms of religious responsibility, Grandison is unwilling to change his faith, and Clementina initially refuses to marry him over his religion.

"[2]: 146–7 Sarah Fielding, in her introduction to The Lives of Cleopatra and Octavia, claims that people have an "insatiable Curiosity for Novels or Romances" that tell of the "rural Innocence of a Joseph Andrews, or the inimitable Virtues of Sir Charles Grandison".

[11] Andrew Murphy, in the Gray's Inn Journal, emphasised the history of the production when he wrote: Mr. Richardson, Author of the celebrated Pamela, and the justly admired Clarissa... an ingenuous Mind must be shocked to find, that Copies of very near all this Work, from which the Public may reasonable expect both Entertainment and Instruction, have been clandestinely and fraudulently obtained by a Set of Booksellers in Dublin, who have printed of the same, and advertised it in the public Papers....

No characters are introduced, but for the purpose of advancing the plot; and there are but few of those digressive dialogues and dissertations with which Sir Charles Grandison abounds.

There is indeed little in the plot to require attention; the various events, which are successively narrated, being no otherwise connected together, than as they place the character of the hero in some new and peculiar point of view.

The same may be said of the numerous and long conversations upon religious and moral topics, which compose so great a part of the work, that a venerable old lady, whom we well knew, when in advanced age, she became subject to drowsy fits, chose to hear Sir Charles Grandison read to her as she sat in her elbow-chair, in preference to any other work, 'because,' said she, 'should I drop asleep in course of the reading, I am sure, when I awake, I shall have lost none of the story, but shall find the party, where I left them, conversing in the cedar-parlour.'

[14]: 234, 423 Later critics believed that it is possible that Richardson's work failed because the story deals with a "good man" instead of a "rake", which prompted Richardson's biographers Thomas Eaves and Ben Kimpel to claim, this "might account for the rather uneasy relationship between the story of the novel and the character of its hero, who is never credible in his double love – or in any love.

"[18] Flynn agrees that this possibility is an "attractive one", and conditions it to say that "it is at least certain that the deadly weighted character of Sir Charles stifles the dramatic action of the book.

"[19]: 243 Some critics, such as Mark Kinkead-Weekes[20]: 291, 4 and Margaret Doody,[21] like the novel and emphasise the importance of the moral themes that Richardson takes up.