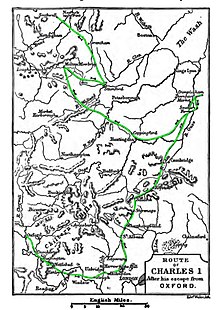

Charles I's journey from Oxford to the Scottish army camp near Newark

Charles I of England left Oxford on 27 April 1646 and travelled by a circuitous route through enemy-held territory to arrive at the Scottish army camp located close to Southwell near Newark-on-Trent on 5 May 1646.

Towards the end of the First English Civil War, Charles I had continued to contact the parties that were opposed to him, hoping to split them apart and gain politically what he was losing militarily.

[5] Gardiner wrote: It was ever Charles's habit to meet difficulties with neatly arranged phrases, rather than with a prompt recognition of the significance of unpleasant facts.Since he had received Montreuil's communication, the Scots had been out of favour with him, and on 23 March, upon the arrival of the bad news of the defeat of the last Royalist field army at the Battle of Stow-on-the-Wold, he despatched a request to the English Parliament for permission to return to Westminster, on the understanding that an act of oblivion was to be passed and all sequestrations to be reversed.

Even had this offer been straightforward, it implied that the central achievement of his opponents in the winning the war should be set aside, and that Charles should be allowed to step back on the throne, free to refuse to assent to any legislation which displeased him.

Montreuil took up lodgings in the large apartment (divided into a dining-room and bedroom) of the inn to the left of the gateway, while the Scots, possibly on the instigation of Edward Cludd, a leading Parliamentarian, made the archbishop's palace their headquarters.

The French Agent is described by Clarendon as a young gentleman of parts very equal to the trust reposed in him, and not inclined to be made use of in ordinary dissimulation and cozenage.

In no hopeful mood, and with no tidings except that Scots had promised to send a party of horse to Burton upon Trent, Hudson returned to Oxford, where further letters from Montreuil were anxiously awaited.

Ashburnham, who was in constant attendance upon him, said in a letter that the king felt he could not refrain from trying to reach the Scots, "first on account of his low condition in point of force, and the strong necessity he is brought into, not being able to supply his table.

The King left secretly on 26 April, accompanied only by John Ashburnham and Michael Hudson, the latter being familiar with the country and able to conduct the little party by the safest route.

Scissors were used to cut the King's tresses and lovelock, and the peak of his beard was clipped off, so that he no longer looked like the man familiar to any who have seen his portraits by Anthony van Dyck.

[17] Hudson had persuaded the King that it was not possible to travel directly from Oxford to the Scottish camp outside Newark-on-Trent, and that it would be better to go by a circuitous route, first towards London, then north-east, before turning north-west towards Newark.

Arriving at Hillingdon, at that time a village near Uxbridge and now in Greater London, the party dallied at the inn for several hours, debating on their future course.

They chose to head towards King's Lynn in Norfolk, which if it proved difficult to reach, or if no ships were available, left the Scottish option still open.

In his statement to Parliament, Hudson said: "The business was concluded, and I returned with the consent of the Scotch Commissioners to the King, whom I found at the sign of the White Swan at Downham.

[17] Hudson later related the contents (when examined by the English Parliament) of the paper he carried (written by Montreuil, in French, because the Scots would not write down their terms): Gardiner makes several points about this Scottish offer.

Lothian expressed surprise at "conditions" that Charles thought he had obtained before his arrival and denied them, adding that they could not be responsible for what their Commissioners in London might have agreed to.

Lothian presented a series of demands to Charles: the surrender of Newark, that he sign the Covenant and order the establishment of Presbyterianism in England and Ireland, and to direct the commander of the Royalist Scottish field army, James Graham, Marquess of Montrose, to lay down his arms.

The first letter on the subject was to the English Commissioners at Newark, in which they said they felt it their duty to acquaint them that the King had come into their army that morning, which they said "has overtaken us unexpectedly, filled us with amazement, and made us like men that dream".

[28] Their next letter on the subject was to the Committee of Both Kingdoms in London, and in it they affirmed that The King came into our army yesterday in so private a way that, after we had made search for him upon the surmises of some persons who pretended to know his face, yet we could not find him out in sundry houses.

[31] Ashburnham took steps to effect this, nominating as negotiators Lord Belasyse, governor of Newark, and Francis Pierrepont (MP), and requested that they communicate with him, but Lord Belasyse told him, when they conversed together after the surrender of Newark, that Pierrepont "would by no means admit any discourse with me in the condition I then stood, the action of waiting on the King to the Scots army rendering me more obnoxious to the Parliament than any man living, and so those thoughts of his Majesty going to the English vanished".