Charles Martel

Continuing and building on his father's work, he restored centralized government in Francia and began the series of military campaigns that re-established the Franks as the undisputed masters of all Gaul.

Pepin's son Charlemagne, grandson of Charles, extended the Frankish realms and became the first emperor in the West since the Fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Older historiography commonly describes Charles as "illegitimate", but the dividing line between wives and concubines was not clear-cut in eighth-century Francia.

[14][15] By Charles's lifetime the Merovingians had ceded power to the Mayors of the Palace, who controlled the royal treasury, dispensed patronage, and granted land and privileges in the name of the figurehead king.

Pepin's death occasioned open conflict between his heirs and the Neustrian nobles who sought political independence from Austrasian control.

The abbey had been built on land donated by Plectrude's mother, Irmina of Oeren, but most of Willibrord's missionary work had been carried out in Frisia.

Gerberding suggests that Willibrord had decided that the chances of preserving his life's work were better with a successful field commander like Charles than with Plectrude in Cologne.

The victorious Charles pursued the fleeing king and mayor to Paris, but as he was not yet prepared to hold the city, he turned back to deal with Plectrude and Cologne.

Upon this success, Charles proclaimed Chlothar IV king in Austrasia in opposition to Chilperic and deposed Rigobert, archbishop of Reims, replacing him with Milo, a lifelong supporter.

When Chilperic II died in 721, Charles appointed as his successor the son of Dagobert III, Theuderic IV, who was still a minor, and who occupied the throne from 721 to 737.

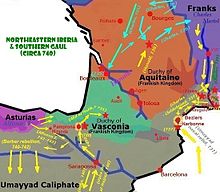

In 731, after defeating the Saxons, Charles turned his attention to the rival southern realm of Aquitaine, and crossed the Loire, breaking the treaty with Duke Odo.

The Continuations of Fredegar allege that Odo called on assistance from the recently established emirate of al-Andalus, but there had been Arab raids into Aquitaine from the 720s onwards.

Whatever the precise circumstances were, it is clear that an army under the leadership of Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi headed north, and after some minor engagements marched on the wealthy city of Tours.

The interregnum, the final four years of Charles' life, was relatively peaceful although in 738 he compelled the Saxons of Westphalia to submit and pay tribute and in 739 he checked an uprising in Provence where some rebels united under the leadership of Maurontus.

He erected four dioceses in Bavaria (Salzburg, Regensburg, Freising, and Passau) and gave them Boniface as archbishop and metropolitan over all Germany east of the Rhine, with his seat at Mainz.

Nonetheless, the pope's request for Frankish protection showed how far Charles had come from the days when he was tottering on excommunication, and set the stage for his son and grandson to assert themselves in the peninsula.

[27] His territories had been divided among his adult sons a year earlier: to Carloman he gave Austrasia, Alemannia, and Thuringia, and to Pippin the Younger Neustria, Burgundy, Provence, and Metz and Trier in the "Mosel duchy".

A ninth-century text, the Visio Eucherii, possibly written by Hincmar of Reims, portrayed Charles as suffering in hell for this reason.

[31] According to British medieval historian Paul Fouracre, this was "the single most important text in the construction of Charles's reputation as a seculariser or despoiler of church lands".

[32] By the eighteenth century, historians such as Edward Gibbon had begun to portray the Frankish leader as the saviour of Christian Europe from a full-scale Islamic invasion.

[33] In the nineteenth century, the German historian Heinrich Brunner argued that Charles had confiscated church lands in order to fund military reforms that allowed him to defeat the Arab conquests, in this way brilliantly combining two traditions about the ruler.

"[34] Many twentieth-century European historians continued to develop Gibbon's perspectives, such as French medievalist Christian Pfister, who wrote in 1911 that "Besides establishing a certain unity in Gaul, Charles saved it from a great peril.

By his able policy Odo succeeded in arresting their progress for some years; but a new vali, Abdur Rahman, a member of an extremely fanatical sect, resumed the attack, reached Poitiers, and advanced on Tours, the holy town of Gaul.

In October 732—just 100 years after the death of Mahomet—Charles gained a brilliant victory over Abdur Rahman, who was called back to Africa by revolts of the Berbers and had to give up the struggle.

[3]Similarly, William E. Watson, who wrote of the battle's importance in Frankish and world history in 1993, suggested that "Had Charles Martel suffered at Tours-Poitiers the fate of King Roderick at the Rio Barbate, it is doubtful that a "do-nothing" sovereign of the Merovingian realm could have later succeeded where his talented major domus had failed.

Indeed, as Charles was the progenitor of the Carolingian line of Frankish rulers and grandfather of Charlemagne, one can even say with a degree of certainty that the subsequent history of the West would have proceeded along vastly different currents had 'Abd al-Rahman been victorious at Tours-Poitiers in 732.

"[35]And in 1993, the influential political scientist Samuel Huntington saw the battle of Tours as marking the end of the "Arab and Moorish surge west and north".

This view is typified by Alessandro Barbero, who in 2004 wrote, "Today, historians tend to play down the significance of the battle of Poitiers, pointing out that the purpose of the Arab force defeated by Charles Martel was not to conquer the Frankish kingdom, but simply to pillage the wealthy monastery of St-Martin of Tours".

[37]Similarly, in 2002 Tomaž Mastnak wrote: "The continuators of Fredegar's chronicle, who probably wrote in the mid-eighth century, pictured the battle as just one of many military encounters between Christians and Saracens—moreover, as only one in a series of wars fought by Frankish princes for booty and territory... One of Fredegar's continuators presented the battle of Poitiers as what it really was: an episode in the struggle between Christian princes as the Carolingians strove to bring Aquitaine under their rule.

In 1620, Andre Favyn stated (without providing a source) that among the spoils Charles's forces captured after the Battle of Tours were many genets (raised for their fur) and several of their pelts.