Charles R. Knight

Though legally blind because of astigmatism he inherited from his father and after his right eye was struck by a rock by a playmate, Knight pursued his artistic talents with the help of specially designed glasses which he used to paint inches from the canvas for the rest of his life.

Wortman was thrilled with the final result, and the museum soon commissioned Knight to produce an entire series of watercolors to grace their fossil halls.

After a tour of Europe by visiting many museums and zoos, Knight returned home where he met two key people in the history of paleontology, Edward Drinker Cope and Henry Fairfield Osborn.

Other familiar American Museum paintings include Knight's portrayals of Agathaumas, Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Brontosaurus, Smilodon, and the Woolly Mammoth.

In 1925, for example, Knight produced an elaborate mural for the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County which portrayed some of the birds and mammals whose remains had been found in the nearby La Brea Tar Pits.

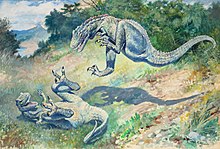

This confrontation scene between a predator and its prey became iconic and inspired a huge number of imitations, establishing these two dinosaurs as "mortal enemies" in the public consciousness.

He also wrote and illustrated several books of his own, such as Before the Dawn of History (Knight, 1935), Life Through the Ages (1946), Animal Drawing: Anatomy and Action for Artists (1947), and Prehistoric Man: The Great Adventure (1949).

Eventually, Knight began to retire from the public sphere to spend more time with his grandchildren, mostly his granddaughter Rhoda, who shared his passion for animals and prehistoric life.

Because Knight worked in an era when new and often fragmentary fossils were coming out of the American west in quantity, not all of his creations were based on solid evidence; dinosaurs such as his improbably-adorned Agathaumas (1897) for example, were somewhat speculative.

His depictions of better-known ceratopsians as solitary animals inhabiting lush grassy landscapes were largely imaginative (the grasslands that feature in many of his paintings didn't appear until the Cenozoic).

In his catalogue to Life through the Ages (1946), he reiterated views that he had written earlier (Knight, 1935), describing the great beasts as "slow-moving dunces" that were "unadaptable and unprogressive" while conceding that small dinosaurs had been more active.

Some of his pictures are now known to be wrong, such as the tripod kangaroo-like posture of the hadrosaurs and theropods, whereas their spinal column was roughly horizontal at the hip; and the sauropods standing deeply in water whereas they were land-dwellers.

[5] Gould writes in his 1989 book Wonderful Life, "Not since the Lord himself showed his stuff to Ezekiel in the valley of dry bones had anyone shown such grace and skill in the reconstruction of animals from disarticulated skeletons.

Charles R. Knight, the most celebrated of artists in the reanimation of fossils, painted all the canonical figures of dinosaurs that fire our fear and imagination to this day".

[9] Other admirers have included special effects artist Ray Harryhausen, who writes in his autobiography An Animated Life, "Long before Obie (Willis O'Brien), myself, and Steven Spielberg, he put flesh on creatures that no human had ever seen.

This, plus a picture book about Knight's work my mother gave me, were my first encounters with a man who was to prove an enormous help when the time came for me to make three-dimensional models of these extinct beings".