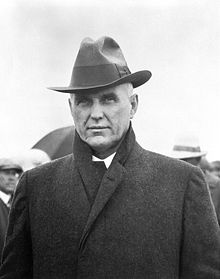

Charles Stewart (premier)

Born in Strabane, Ontario, in then Wentworth County (now part of Hamilton), Stewart was a farmer who moved west to Alberta after his farm was destroyed by a storm.

Unable to match the UFA's appeal to rural voters, Stewart's government was defeated at the polls and he was succeeded as premier by Herbert Greenfield.

After leaving provincial politics, Stewart was invited to join the federal cabinet of William Lyon Mackenzie King, in which he served as Minister of the Interior and Mines.

In this capacity he signed, on behalf of the federal government, an agreement that transferred control of Alberta's natural resources from Ottawa to the provincial government—a concession he had been criticized for being unable to negotiate as Premier.

According to family lore, Macdonald noticed the young future Premier and told him that he was a fine boy who would make a good politician someday.

His family endured a cold winter—the warmest place in their shack was on the kitchen table, so they kept the baby there—and in the spring their crops were destroyed by hail.

As he was unsuccessful at farming, he supplemented his income using the stonemason's skills he had learned from his father: he laid foundations for the Canadian Pacific Railway, worked on the High Level Bridge in Edmonton, and dug Killam's town well.

[7] As was required by the custom of the day when an MLA was appointed to cabinet, he resigned his seat to run in a by-election, in which he easily defeated Conservative William John Blair.

[9] Despite this position, he backed Sifton's 1913 resolution to the Alberta and Great Waterways problem, which involved partnering with the private sector; this vote marked the first time that the Liberal caucus was united on the railways question since before the scandal broke in 1910.

[9] The Alberta and Great Waterways scandal had opened up a rift in the provincial Liberal Party, between those who remained loyal to Cross and Rutherford and those who did not, with the latter group being led by William Henry Cushing and Frank Oliver.

[14] This time, however, the fault lines were different: Cross and Oliver had put aside their longtime enmity to join in opposing conscription, and Sifton, who had been selected Premier in part because he was not identified with either faction in the old feud, was Alberta's most prominent pro-conscription Liberal.

Alexander Grant MacKay criticized his failure to take advantage of the recent conference of premiers to press for the transfer of rights over Alberta's natural resources from the federal to the provincial government (Sifton had made this a priority during the pre-war years, but had largely ceased his advocacy on the breakout of hostilities), and James Gray Turgeon attacked the government's policy of levying taxes for the support of soldiers' dependants on the grounds that he considered it a federal responsibility.

[19] By the time Stewart took office, it was becoming apparent that the policy was not being universally complied with: Conservative MLA George Douglas Stanley alleged that judges were often hungover when they sat in judgment of those accused of violating liquor laws, and Cross's replacement as Attorney-General, John Boyle, admitted that in his estimation 65% of the province's male population broke the Prohibition Act.

[23] However, a committee formed to examine the possibility disintegrated over what historian Carrol Jaques calls "battles within the group and a general dislike of the concept".

[24] Railway development had dominated the premierships of Stewart's predecessors and, while losing political potency as an issue, it was still a matter that demanded his attention.

As with railways, the First World War had disrupted planned irrigation projects, and Albertan farmers, especially those from the arid south, were eager to see them resumed.

[24] When Peace River MLA William Archibald Rae introduced legislation to allow Imperial Oil to build a pipeline in the province, UFA President Henry Wise Wood sent Stewart a telegram of protest, as he believed that pipelines should be common carriers;[30] Stewart read it in the legislature, and Rae's bill was withdrawn.

[33] In fact, it ended up doing so somewhat sooner: in 1919, Charles W. Fisher, Liberal MLA for Cochrane, died as a result of that year's influenza epidemic, and a by-election was necessitated to replace him.

Stewart believed that "the more strongly armed the classes become the harder will it be to get the things we really need in our government" and asserted that "I never did and never will have any desire to form a coalition with anybody except with men who think the same as I do.

[40] Though the Liberals' fortunes had been sagging in the post-war years, there remained no doubt that they could again defeat the Conservatives; their real challenge was evidently from the newly politicized UFA.

[37] Historian L. G. Thomas recognized Stewart's admirable qualities,[17] but criticized him for lacking Sifton's "ruthless and forceful leadership"[44] and claimed that "few provincial premiers have been more universally praised by their opponents and more unanimously deplored by their supporters.

They had not won any seats in Alberta, and Stewart was invited to join King's cabinet as Minister of the Interior and Mines (which included responsibility as Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs).

After it was signed but before it took effect, Manitoba Premier John Bracken concluded an agreement with the Winnipeg Electric Company, a private concern, to develop a hydroelectric dam at Seven Sisters' Reach.

[49] Stewart's preference for public over private ownership extended to King's planned creation of the Bank of Canada; Stewart wanted the new institution entirely under the control of the government, but King preferred an arrangement whereby half of its directors would be appointed by the government and half by private shareholders and suggested that advocates of public ownership might find themselves more at home in the socialist Cooperative Commonwealth Federation than in his Liberal caucus.

[50] Despite Stewart's involvement in transferring resource rights to Alberta, his relationship with the UFA government that had defeated him in 1921 was frosty: Lakeland College historian Franklin Foster, in his biography of UFA Premier John Edward Brownlee, alleges that this antipathy influenced Stewart's preference for private corporations over the Alberta government in granting hydroelectric power permits.

[59] By 1925 he was considering appointing Stewart to the Senate, to remove him from active political involvement, but was handicapped by the absence of any other Alberta representation in his cabinet.

"[64] When Stewart too went down to defeat in 1935, King was pleased "not to have to consider him" in assembling his new cabinet, and opted instead to leave Alberta unrepresented to punish it for failing to elect any Liberals.