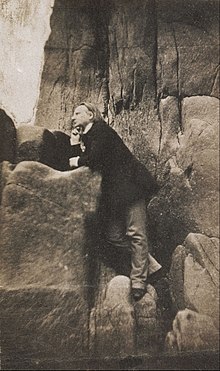

Victor Hugo

Although he was a committed royalist when young, Hugo's views changed as the decades passed, and he became a passionate supporter of republicanism, serving in politics as both deputy and senator.

Madame Hugo and her children were sent back to Paris in 1808, where they moved to an old convent, 12 Impasse des Feuillantines, an isolated mansion in a deserted quarter of the left bank of the Seine.

Hiding in a chapel at the back of the garden was de La Horie, who had conspired to restore the Bourbons and been condemned to death a few years earlier.

Though the poems were admired for their spontaneous fervor and fluency, the collection that followed four years later in 1826 (Odes et Ballades) revealed Hugo to be a great poet, a natural master of lyric and creative song.

Le Dernier jour d'un condamné (The Last Day of a Condemned Man) would have a profound influence on later writers such as Albert Camus, Charles Dickens, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

[20] Hernani announced the arrival of French romanticism: performed at the Comédie-Française, it was greeted with several nights of rioting as romantics and traditionalists clashed over the play's deliberate disregard for neo-classical rules.

Hugo began planning a major novel about social misery and injustice as early as the 1830s, but a full 17 years were needed for Les Misérables to be realised and finally published in 1862.

[22] Hugo was acutely aware of the quality of the novel, as evidenced in a letter he wrote to his publisher, Albert Lacroix, on 23 March 1862: "My conviction is that this book is going to be one of the peaks, if not the crowning point of my work.

The Belgian publishing house Lacroix and Verboeckhoven undertook a marketing campaign unusual for the time, issuing press releases about the work a full six months before the launch.

Dedicated to the channel island of Guernsey, where Hugo spent 15 years of exile, the novel tells of a man who attempts to win the approval of his beloved's father by rescuing his ship, intentionally marooned by its captain who hopes to escape with a treasure of money it is transporting, through an exhausting battle of human engineering against the force of the sea and an almost mythical beast of the sea, a giant squid.

Superficially an adventure, one of Hugo's biographers calls it a "metaphor for the 19th century–technical progress, creative genius and hard work overcoming the immanent evil of the material world.

Hugo returned to political and social issues in his next novel, L'Homme Qui Rit (The Man Who Laughs), which was published in 1869 and painted a critical picture of the aristocracy.

A group of French academicians, particularly Étienne de Jouy, were fighting against the "romantic evolution" and had managed to delay Victor Hugo's election.

On the nomination of King Louis-Philippe, Hugo entered the Upper Chamber of Parliament as a pair de France in 1845, where he spoke against the death penalty and social injustice, and in favour of freedom of the press and self-government for Poland.

He moved to Brussels, then Jersey, from which he was expelled for supporting L'Homme, a local newspaper that had published a letter to Queen Victoria by a French republican deemed treasonous.

In a speech delivered on 18 May 1879, during a banquet to celebrate the abolition of slavery, in the presence of the French abolitionist writer and parliamentarian Victor Schœlcher, Hugo declared that the Mediterranean Sea formed a natural divide between "ultimate civilisation and... utter barbarism."

It was only after Napoleon III fell from power and the Third Republic was proclaimed that Hugo finally returned to his homeland in 1870, where he was promptly elected to the National Assembly and the Senate.

He had been in Brussels since 22 March 1871 when in the 27 May issue of the Belgian newspaper l'Indépendance Victor Hugo denounced the government's refusal to grant political asylum to the Communards threatened with imprisonment, banishment or execution.

[43] This caused so much uproar that in the evening a mob of fifty to sixty men attempted to force their way into the writer's house shouting, "Death to Victor Hugo!

He frequented spiritism during his exile (where he participated also in many séances conducted by Madame Delphine de Girardin)[48][49] and in later years settled into a rationalist deism similar to that espoused by Voltaire.

[52] Yet he believed in life after death and prayed every single morning and night, convinced as he wrote in The Man Who Laughs that "Thanksgiving has wings and flies to its right destination.

Hugo also worked with composer Louise Bertin, writing the libretto for her 1836 opera La Esmeralda, which was based on the character in The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

In particular, Hugo's plays, in which he rejected the rules of classical theatre in favour of romantic drama, attracted the interest of many composers who adapted them into operas.

Additionally, Hugo's poems have attracted an exceptional amount of interest from musicians, and numerous melodies have been based on his poetry by composers such as Berlioz, Bizet, Fauré, Franck, Lalo, Liszt, Massenet, Saint-Saëns, Rachmaninoff, and Wagner.

For instance, in 2009, Italian composer Matteo Sommacal was commissioned by Festival "Bagliori d'autore" and wrote a piece for speaker and chamber ensemble entitled Actes et paroles, with a text elaborated by Chiara Piola Caselli after Victor Hugo's last political speech addressed to the Assemblée législative, "Sur la Revision de la Constitution" (18 July 1851),[63] and premiered in Rome on 19 November 2009, in the auditorium of the Institut français, Centre Saint-Louis, French Embassy to the Holy See, by Piccola Accademia degli Specchi featuring the composer Matthias Kadar [nl].

Every inch and detail of the event was for Hugo; the official guides even wore cornflowers as an allusion to Fantine's song in Les Misérables.

They also reported from a reliable source that at one point in the night he had whispered the following alexandrin, "En moi c’est le combat du jour et de la nuit.

Originally pursued as a casual hobby, drawing became more important to Hugo shortly before his exile when he made the decision to stop writing to devote himself to politics.

He sought a wide variety of women of all ages, be they courtesans, actresses, prostitutes, admirers, servants or revolutionaries like Louise Michel for sexual activity.

The people of Guernsey erected a statue by sculptor Jean Boucher in Candie Gardens (Saint Peter Port) to commemorate his stay in the islands.

1 June 1885.