Paris Commune

On 31 October, the leaders of the main revolutionary groups in Paris, including Blanqui, Félix Pyat and Louis Charles Delescluze, called new demonstrations at the Hôtel de Ville against General Trochu and the government.

Shots were fired from the Hôtel de Ville, one narrowly missing Trochu, and the demonstrators crowded into the building, demanding the creation of a new government, and making lists of its proposed members.

While the formation of the new government was taking place inside the Hôtel de Ville, however, units of the National Guard and the Garde Mobile loyal to General Trochu arrived and recaptured the building without violence.

[20] In September and October, Adolphe Thiers, the leader of the National Assembly conservatives, had toured Europe, consulting with the foreign ministers of Britain, Russia, and Austria-Hungary, and found that none of them were willing to support France against the Germans.

General Trochu received reports from the prefect of Paris that agitation against the government and military leaders was increasing in the political clubs and in the National Guard of the working-class neighbourhoods of Belleville, La Chapelle, Montmartre, and Gros-Caillou.

The plan was initially opposed by War Minister Adolphe Le Flô, d'Aurelle de Paladines, and Vinoy, who argued that the move was premature, because the army had too few soldiers, was undisciplined and demoralized, and that many units had become politicized and were unreliable.

[29] While the Army had succeeded in securing the cannons at Belleville and Buttes-Chaumont and other strategic points, at Montmartre a crowd gathered and continued to grow, and the situation grew increasingly tense.

General Lecomte and his staff officers were seized by the guardsmen and his mutinous soldiers and taken to the local headquarters of the National Guard under the command of captain Simon Charles Mayer[30] at the ballroom of the Chateau-Rouge.

At about 5:30 on 18 March, the angry crowd of national guardsmen and deserters from Lecomte's regiment at rue des Rosiers seized Clément-Thomas, beat him with rifle butts, pushed him into the garden, and shot him repeatedly.

[55][56] Louise Michel, the famed "Red Virgin of Montmartre" (see photo), who would later be deported to New Caledonia, was one of those who symbolised the active participation of a small number of women in the insurrectionary events.

Another highly popular publication was Le Père Duchêne, inspired by a similar paper of the same name published from 1790 until 1794; after its first issue on 6 March, it was briefly closed by General Vinoy, but it reappeared until 23 May.

On 21 March, they occupied the fort of Mont-Valérien where the Commune's fédérés had neglected to settle: this position which dominated the entire near western suburbs of Paris gave them a considerable advantage.

[65] By April, as MacMahon's forces steadily approached Paris, divisions arose within the Commune about whether to give absolute priority to military defence, or to political and social freedoms and reforms.

He recruited officers with military experience, particularly Poles who had fled to France in 1863, after the Russians quelled the January Uprising; they played a prominent role in the last days of the Commune.

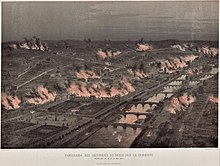

On 20 May, MacMahon's artillery batteries at Montretout, Mont-Valerian, Boulogne, Issy, and Vanves opened fire on the western neighbourhoods of the city—Auteuil, Passy, and Trocadéro—with shells falling close to l'Étoile.

"[72] On 19 May, while the Commune executive committee was meeting to judge the former military commander Cluseret for the loss of the Issy fortress, it received word that the forces of Marshal MacMahon were within the fortifications of Paris.

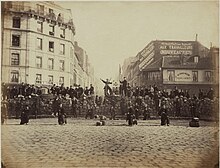

[79] Once the fighting began inside Paris, the strong neighborhood loyalties that had been an advantage of the Commune became something of a disadvantage: instead of an overall planned defence, each "quartier" fought desperately for its survival, and each was overcome in turn.

The webs of narrow streets that made entire districts nearly impregnable in earlier Parisian revolutions had in the centre been replaced by wide boulevards during Haussmann's renovation of Paris.

On the same day, the first executions of National Guard soldiers by the regular army inside Paris took place; some sixteen prisoners captured on the rue du Bac were given a summary hearing, and then shot.

The Tuileries Palace, which had been the residence of most of the monarchs of France from Henry IV to Napoleon III, was defended by a garrison of some three hundred National Guard with thirty cannon placed in the garden.

[86] In addition to public buildings, the National Guard also started fires at the homes of a number of residents associated with the regime of Napoleon III, including that of historian and playwright Prosper Mérimée, author of Carmen.

Wounded men were being tended in the halls, and some of the National Guard officers and Commune members were changing from their uniforms into civilian clothes and shaving their beards, preparing to escape from the city.

On 24 May, a delegation of national guardsmen and Gustave Genton, a member of the Committee of Public Safety, came to the new headquarters of the Commune at the city hall of the 11th arrondissement and demanded the immediate execution of the hostages held at the prison of La Roquette.

At about seven-thirty, Delescluze put on his red sash of office, walked unarmed to the barricade on the Place du Château-d'Eau, climbed to the top and showed himself to the soldiers, and was promptly shot dead.

[7] On the morning of 27 May, the regular army soldiers of Generals Grenier, Paul de Ladmirault and Jean-Baptiste Montaudon launched an attack on the National Guard artillery on the heights of the Buttes-Chaumont.

[8] A separate and more formal trial was held beginning 7 August for the Commune leaders who survived and had been captured, including Théophile Ferré, who had signed the death warrant for the hostages, and the painter Gustave Courbet, who had proposed the destruction of the column in Place Vendôme.

Marx and Engels, Mikhail Bakunin, and later Lenin, tried to draw major theoretical lessons (in particular as regards the "dictatorship of the proletariat" and the "withering away of the state") from the limited experience of the Commune.

"[125] Engels echoed his partner, maintaining that the absence of a standing army, the self-policing of the "quarters", and other features meant that the Commune was no longer a "state" in the old, repressive sense of the term.

[135] Another French historian, Paul Lidsky, argues that Thiers felt urged by mainstream newspapers and leading intellectuals to take decisive action against 'the social and democratic vermin' (Le Figaro), 'those abominable ruffians' (Countess of Ségur).

"[146] During the phase of the Cultural Revolution where mass political mobilization was trending downward, the Shengwulian (an ultraleft group in Hunan province) modeled its ideology on the radically egalitarian nature of the Paris Commune.

Kliment Voroshilov is at right, Grigory Zinoviev third from right, Avel Enukidze fourth, and Nikolay Antipov fifth.