Chemical formula

Molecular formulae indicate the simple numbers of each type of atom in a molecule, with no information on structure.

For example, glucose shares its molecular formula C6H12O6 with a number of other sugars, including fructose, galactose and mannose.

An example is boron carbide, whose formula of CBn is a variable non-whole number ratio with n ranging from over 4 to more than 6.5.

However, except for very simple substances, molecular chemical formulae lack needed structural information, and are ambiguous.

Condensed chemical formulae may also be used to represent ionic compounds that do not exist as discrete molecules, but nonetheless do contain covalently bound clusters within them.

Each polyatomic ion in a compound is written individually in order to illustrate the separate groupings.

In chemistry, the empirical formula of a chemical is a simple expression of the relative number of each type of atom or ratio of the elements in the compound.

An empirical formula makes no reference to isomerism, structure, or absolute number of atoms.

Likewise the empirical formula for hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, is simply HO, expressing the 1:1 ratio of component elements.

A condensed (or semi-structural) formula may represent the types and spatial arrangement of bonds in a simple chemical substance, though it does not necessarily specify isomers or complex structures.

The two lines (or two pairs of dots) indicate that a double bond connects the atoms on either side of them.

This condensed structural formula implies a different connectivity from other molecules that can be formed using the same atoms in the same proportions (isomers).

The same number of atoms of each element (10 hydrogens and 4 carbons, or C4H10) may be used to make a straight chain molecule, n-butane: CH3CH2CH2CH3.

For more complex ions, brackets [ ] are often used to enclose the ionic formula, as in [B12H12]2−, which is found in compounds such as caesium dodecaborate, Cs2[B12H12].

Parentheses ( ) can be nested inside brackets to indicate a repeating unit, as in Hexamminecobalt(III) chloride, [Co(NH3)6]3+Cl−3.

[further explanation needed] This is strictly optional; a chemical formula is valid with or without ionization information, and Hexamminecobalt(III) chloride may be written as [Co(NH3)6]3+Cl−3 or [Co(NH3)6]Cl3.

Brackets, like parentheses, behave in chemistry as they do in mathematics, grouping terms together – they are not specifically employed only for ionization states.

This is convenient when writing equations for nuclear reactions, in order to show the balance of charge more clearly.

The @ symbol (at sign) indicates an atom or molecule trapped inside a cage but not chemically bound to it.

The choice of the symbol has been explained by the authors as being concise, readily printed and transmitted electronically (the at sign is included in ASCII, which most modern character encoding schemes are based on), and the visual aspects suggesting the structure of an endohedral fullerene.

Such a formula might be written using decimal fractions, as in Fe0.95O, or it might include a variable part represented by a letter, as in Fe1−xO, where x is normally much less than 1.

For example, alcohols may be represented by the formula CnH2n + 1OH (n ≥ 1), giving the homologs methanol, ethanol, propanol for 1 ≤ n ≤ 3.

[4] It is the most commonly used system in chemical databases and printed indexes to sort lists of compounds.

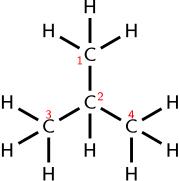

Molecular formula: C 4 H 10

Condensed formula: (CH 3 ) 3 CH

The "@" notation: M@C 60