Chemical weapons in World War I

[1][2] They were primarily used to demoralize, injure, and kill entrenched defenders, against whom the indiscriminate and generally very slow-moving or static nature of gas clouds would be most effective.

[8] In October 1914, German troops fired fragmentation shells filled with a chemical irritant against British positions at Neuve Chapelle; the concentration achieved was so small that it too was barely noticed.

[12] German chemical companies BASF, Hoechst and Bayer (which formed the IG Farben conglomerate in 1925) had been making chlorine as a by-product of their dye manufacturing.

[13] In cooperation with Fritz Haber of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Berlin, they began developing methods of discharging chlorine gas against enemy trenches.

The deaths of so many English officers from gas at this time would certainly have been met with outrage, but a recent, extensive study of British reactions to chemical warfare says nothing of this supposed attack.

At 17:30, in a slight easterly breeze, the liquid chlorine was siphoned from the tanks, producing gas which formed a grey-green cloud that drifted across positions held by troops of the 45th Infantry Division (France), specifically the 1st Tirailleurs and the 2nd Zouaves from Algeria.

The German infantry were also wary of the gas and, lacking reinforcements, failed to exploit the break before the 1st Canadian Division and assorted French troops reformed the line in scattered, hastily prepared positions 1,000–3,000 yards (910–2,740 m) apart.

[9] The Entente governments claimed the attack was a flagrant violation of international law but Germany argued that the Hague treaty had only banned chemical shells, rather than the use of gas projectors.

Simple pad respirators similar to those issued to German troops were soon proposed by Lieutenant-Colonel N. C. Ferguson, the Assistant Director Medical Services of the 28th Division.

[36] In the first combined chlorine–phosgene attack by Germany, against British troops at Wieltje near Ypres, Belgium on 19 December 1915, 88 tons of the gas were released from cylinders causing 1069 casualties and 69 deaths.

The modified PH Gas Helmet, which was impregnated with phenate hexamine and hexamethylene tetramine (urotropine) to improve the protection against phosgene, was issued in January 1916.

Great mustard-coloured blisters, blind eyes, all sticky and stuck together, always fighting for breath, with voices a mere whisper, saying that their throats are closing and they know they will choke.

[52][53] Also the prevailing wind on the Western Front was blowing from west to east,[54] which meant the Allies more frequently had favourable conditions for a gas release than did the Germans.

When the United States entered the war, it was already mobilizing resources from academic, industry and military sectors for research and development into poison gas.

The Protocol, which was signed by most First World War combatants in 1925, bans the use (but not the stockpiling or production) of lethal gas and bacteriological weapons among signatories in international armed conflicts.

The full conflict's use of such weaponry killed around 20,000 Iranian troops (and injured another 80,000), around a quarter of the number of deaths caused by chemical weapons during the First World War.

[66] The Geneva Protocol, signed by 132 nations on June 17, 1925, was a treaty established to ban the use of chemical and biological weapons among signatories in international armed conflicts.

[63] As stated by Coupland and Leins, "it was fostered in part by a 1918 appeal in which the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) described the use of poisonous gas against soldiers as a barbarous invention which science is bringing to perfection".

The Protocol does not ban the stockpilling or production of chemical weapons[70] as well as the use of such weaponry against non-ratifying states and in internal disturbances or conflicts, and permits reservations that allow signatories to adopt the policy of no first use.

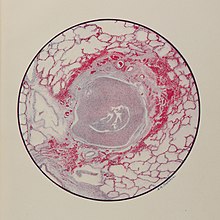

According to Denis Winter (Death's Men, 1978), a fatal dose of phosgene eventually led to "shallow breathing and retching, pulse up to 120, an ashen face and the discharge of four pints (2 litres) of yellow liquid from the lungs each hour for the 48 of the drowning spasms."

One of the most famous First World War paintings, Gassed by John Singer Sargent, captures such a scene of mustard gas casualties which he witnessed at a dressing station at Le Bac-du-Sud near Arras in July 1918.

Regardless, a significant number would be exposed, with the most serious case in Armentières where lingering mustard gas residue from heavy German bombardment in July 1917 led to 675 civilian casualties (including 86 killed).

In addition, around 4000 civilians working in chemical weapons production and shell filling in France, Britain and the United States were injured due to accidental exposure.

At Ypres a Canadian medical officer, who was also a chemist, quickly identified the gas as chlorine and recommended that the troops urinate on a cloth and hold it over their mouth and nose.

Urine would be left to sit for a period so that the ammonia would activate; this would neutralize some of the chemicals in the chlorine gas, which allowed them to delay the German advance at Ypres, giving the allies time to reinforce the area when French and other colonial troops had retreated.

The adjutant of the 1/23rd Battalion, The London Regiment, recalled his experience of the P helmet at Loos: The goggles rapidly dimmed over, and the air came through in such suffocatingly small quantities as to demand a continuous exercise of will-power on the part of the wearers.

The SBR was the prized possession of the ordinary infantryman; when the British were forced to retreat during the German spring offensive of 1918, it was found that while some troops had discarded their rifles, hardly any had left behind their respirators.

The main advantage of this method was that it was relatively simple and, in suitable atmospheric conditions, produced a concentrated cloud capable of overwhelming the gas mask defences.

Livens in 1917) was a simple device; an 8-inch (200 mm) diameter tube sunk into the ground at an angle, a propellant was ignited by an electrical signal, firing the cylinder containing 30 or 40 lb (14 or 18 kg) of gas up to 1,900 metres.

[94] For example, in Verdun, France, the thermal destruction of weapons "resulted in severe metal contamination of upper 4–10 cm of topsoil" at the Place à Gas disposal site.