Cherokee Commission

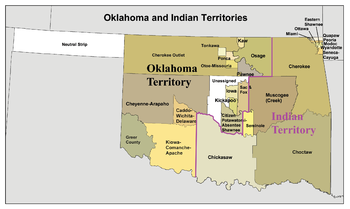

The Commission's purpose was to legally acquire land already occupied by the Cherokee Nation and other tribes in the new Oklahoma Territory for non-indigenous homestead acreage.

Additional lawsuits, further U.S. Supreme Court rulings, further investigations and mandated compensation for irregularities ensued for another 110 years of controversy through the end of the 20th century.

On March 2, 1889, the then 22nd President Grover Cleveland (1837-1908, served 1885-1889 & 1893-1897), two days before he left office (for an interim of four years), signed the Indian Appropriations Act into law.

Section 14 of the Act authorized the President to appoint a three-person bi-partisan commission to negotiate with the Cherokee and other tribes in the Indian Territory for cession of their lands to the United States and its federal government.

Harrison administration Secretary Noble's initial directive to the Commission was to offer $1.25 per acre, but to adjust that amount if the situation favored it.

[15][16] Angus Cameron (1826-1897), of Wisconsin was then selected by the Chief Executive to replace Fairchild to serve as the second Chairman of the Commission, but he too resigned after only three weeks.

[18] John F. Hartranft (1830-1889), recipient of the famous congressional Medal of Honor[19] and the former Governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, became the initial third person on the committee.

[25] In May 1890, the Commission under David H. Jerome returned for negotiations, notifying the tribe of an October cessation to cattle grazing leases.

The Fox and Sac National Council was credited with uplifting the morality of the tribe by prohibiting polygamy, and requiring lawful marriages.

Keokuk and the Sac and Fox National Council forced the Commission to agree to 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) per person, regardless of age or marital status.

[42] In 1999, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that only the Potawatomi had proprietary rights to the reservation land ceded in 1890, so the Absentee-Shawnee were unable to share in the 1968 award for under payment.

[48] The Ghost Dance religion, as practiced by a Northern Paiute named Wovoka made its influence felt among the Arapaho at this time.

Wovoka was the son of a prophet named Tavibo, and according to historian James Mooney, was considered "The Messiah" of the Ghost Dance.

Jerome received instructions from Noble to follow the Treaty of Medicine Lodge directive in getting three-fourths of adult males to sign the agreement.

[55] Noble learned that Cheyenne chiefs Whirlwind, Old Crow, Little Medicine, Howling Wolf and Little Big Jake were in disagreement with the Commission over the attorney contract.

Allotments of 160 acres (0.65 km2; 0.25 sq mi) per person were to be selected by the individual tribal members within 90 days of Congressional ratification of the agreement.

Painter's investigative findings were published by the Indian Rights Association in 1893 as Cheyennes and Araphos Revisited and a Statement of Their Contract with Attorneys.

[75] On June 4, 1891 at Anadarko, the Agreement with the Wichita and Affiliated Bands (1891) ceded their surplus land, with Congress setting the price per acre.

[84] Quaker field matron Elizabeth Test reported in August 1894, that most Kickapoo did not understand that the agreement meant they were giving up their land.

[90] The Tonkawa hired legal counsel and claimed they had been pressured into signing the agreement, under the threat that all their allotments would be canceled if they failed to capitulate.

[93] Tribal chief Joel B. Mayes was a graduate of Cherokee Male Seminary, a former school teacher, and a veteran of the Confederate First Indian Regiment during the Civil War.

[10] The majority of Cherokees did not want to sell the Outlet land, and Chief Mayes was focused on potential increase in tribal income by hiking taxes to cattlemen.

Empowered by the Cherokee National Council, Mayes appointed a nine-member committee: Stan W. Gray as Chairman, William P. Ross, Johnson Spade, Rabbit Bunch, L.B.

[103] The United States House Committee on Territories recommended in February 1891 bypassing negotiations and annexing the Outlet, paying the Cherokees $1.25 an acre as a settlement.

A main point of contention in the negotiations was the question of intruders, outside workers residing on Cherokee land, and the history of the United States failing to handle the problem.

[122] Indian agent George D. Day spoke on October 5, telling the assemblage that the commissioners were their friends, and they could either accept the Commission's offer, or be forced into allotment by the Dawes Act.

[126] On October 22 on Fort Sill, the Commission notified the President they had the required number of signatures for the Agreement with the Comanche, Kiowa and Apache (1892).

Upon the onset of the allotment process, Lone Wolf filed a complaint with the Supreme Court in the District of Columbia, seeking an injunction against the Department of Interior.

The complaint alleged that the agreement was unconstitutional on the grounds that it conflicted with the Treaty of Medicine Lodge requirement of signatures of three-fourths of all tribal adult males.

The report contains a section on the Pawnee participation in the Ghost Dance, which promised to bring a new messiah to force intruders off their land, and return the buffalo.