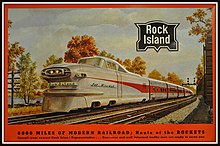

Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad

Construction continued on through La Salle, and Rock Island was reached on February 22, 1854, becoming the first railroad to connect Chicago with the Mississippi River.

The Rock Island stretched across Arkansas, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Texas.

In competition with the Santa Fe Chiefs, the Rock Island jointly operated the Golden State Limited (Chicago—Kansas City—Tucumcari—El Paso—Los Angeles) with the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP) from 1902 to 1968.

The Golden Rocket was scheduled to closely match the Santa Fe's transit time end-to-end and was to have its own dedicated trainsets, one purchased by the Rock Island, the other by Southern Pacific.

The Rock Island conceded nothing to its rival, even installing ABS signaling on the route west of Lincoln in an effort to maintain transit speed.

Finally, in 1970, the train was cut back to a Chicago-Rock Island run entirely within the confines of the state of Illinois and renamed the Quad Cities Rocket.

The track program of 1978 helped with main-line timekeeping, although the Rock Island's management decreed that the two trains were not to delay freight traffic on the route.

From the 1920s on, the suburban services were operated using Pacific-type 4-6-2 locomotives and specially designed light-heavyweight coaches that with their late 1920s build dates became known as the "Capone" cars.

On the Rock Island, the Capone cars were entering their sixth decade of service and the nearly 30-year-old 2700s suffered from severe corrosion due to the steel used in their construction.

LaSalle Street Station, the service's downtown terminal, suffered from neglect and urban decay with the slab roof of the train shed literally falling apart, requiring its removal.

In 1976, the entire Chicago commuter rail system began to receive financial support from the state of Illinois through the Regional Transportation Authority.

As the aura from those days waned in the late 1950s, the Rock Island found itself faced with flat traffic, revenues, and increasing costs.

Despite this, the property was still in decent shape, making the Rock Island an attractive bride for another line looking to expand the reach of their current system.

In 1964, its last profitable year,[9][10] the Rock Island agreed to pursue a merger plan with the UP, which would form one large "super" railroad stretching from Chicago to the West Coast.

Facing the loss of the UP's traffic at the Omaha gateway, virtually every railroad directly and indirectly affected by the potential UP/Rock Island merger immediately filed protests to block it.

After 10 years of hearings and tens of thousands of pages of testimony and exhibits produced, Klitenic, now an administrative law judge, approved the Rock Island-Union Pacific merger as part of a larger plan for rail service throughout the West.

In an effort to prop up its future merger mate, UP asked the Rock Island to forsake the Denver gateway in favor of increased interchange at Omaha.

The cost-cutting measures enacted to conserve cash for the merger left the Rock Island property in such a state that the Union Pacific viewed the expense of bringing it back to viable operating condition to be severely prohibitive.

The visionary plan would not be realized until the megamergers of the 1990s with the BNSF Railway and Union Pacific remaining as the two surviving major rail carriers west of the Mississippi.

However, the FRA-backed loans that Ingram sought were thwarted by the lobbying efforts of competing railroads, which saw a healthy Rock Island as a threat to their own survival.

The Rock Island offered to open the books to show the precarious financial condition of the road in an effort to get the BRAC in line with the other unions that had already signed agreements.

"[13] Seeing the trains rolling despite the strike and fearing a Florida East Coast strikebreaking situation, the unions appealed to the FRA and ICC for relief.

[14] The Directed Service Order enabled one-time suitors, via KCT management, to basically test operate portions of the Rock Island that had once interested them.

Kansas City Terminal began the process of embargoing in-bound shipments in late February, and the final train battled three days of snow drifts to arrive in Denver on March 31, 1980.

Cars and locomotives were gathered in 'ghost trains' that appeared on otherwise defunct Rock Island lines and accumulated at major terminals and shops and prepared for sale.

Henry Crown was ultimately proven correct, as both he and other bondholders who had purchased Rock Island debt for cents on the dollar during the low ebb in prices did especially well.

[16] Ironically, through the megamergers of the 1990s, the Union Pacific ultimately ended up owning and operating more of the Rock Island than it would have acquired in its attempted 1964 merger.

A spur of the Rock Island Railroad that ran beside a small hotel in Eldon, Missouri, owned by the grandmother of Mrs. Paul (Ruth) Henning also inspired the popular television show Petticoat Junction in the early 1960s.

Ruth Henning is listed as a co-creator of the show, along with her husband Paul, who also created The Beverly Hillbillies and executive produced Jay Sommers's Green Acres.

After the closing in 1980, the workshop was sold to National Railway Equipment, and it remained a maintenance and refurbishment hub for the wider North American railroad industry.