Chicago Central Area Transit Plan

Volume 2 included detailed preliminary plans, architectural, and engineering drawings, which were to be the basis for construction contracts for the proposed loop and distributor subway systems.

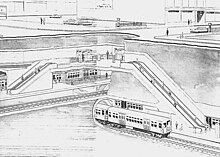

Throughout its entire life, the two-mile (3 km), double-track loop elevated in Chicago's central area has coexisted with strong pressures, political and civic, to do away with it in favor of new downtown subways.

Since its October 1897 opening, the Union Loop Elevated has provided rail rapid transit service to the Chicago central business district.

Although development of major high-rise construction went well beyond its physical limits, its presence and configuration originally defined the most prestigious locations for offices and gave the central business district of Chicago its name, the "Loop".

This was followed by various traction plans presented by the City from the early twentieth century through the 1930s, all of which called for a unified system of surface, elevated and subway lines in the Loop.

The main objectives were to produce a definitive plan to improve distribution of rapid transit and commuter railroad passengers in the Central Area, to permit removal of the "L" structures in the Loop, and to extend the rapid transit system to sectors of downtown Chicago not presently served – thereby assuring that people working and visiting the Central Area could move about faster, easier, and in a more pleasant environment.

Stations planned for the loop subway system were to be located at North/Clybourn, Chicago/Orleans, Merchandise Mart, Roosevelt/Franklin, Ashland/Lake, and Canal/Randolph (directly linked to the present-day Ogilvie Transportation Center).

The latter branch was to consist of two tracks leaving the subway at Adams Street and occupy Illinois Central Railroad right-of-way at grade to the Stevenson Expressway.

The double-track line to the north was to follow an alignment just east of Michigan Avenue under Stetson Street to the Chicago River serving the Prudential Building and the Illinois Center.

The total daily distributor subway travel by passengers who transferred to or from the commuter railroads (today's Metra and Amtrak) or other CTA rapid transit lines would have been twice these volumes.

The Chicago Central Area Transit Plan's financial recommendations were, in retrospect, overly optimistic even for those days before the runaway inflation of the late 1960s and 1970s.

In June, the CUTD was approved by public referendum with the power to levy taxes to provide the local share of funds for the Chicago Central Area Transit Project, which might have been the seed money for massive Federal assistance, at last, to bury the venerable Union Loop.

In the early 1970s, while final planning was underway for a start on the new downtown subways, controversy began swirling in the District over the validity of the project and its cost.

It also explored the relationship of the CCATP with downtown parking facilities and the pedestrian passageway system, existing and planned for the Central Business District.

In 1973, the CUTD retained another consultant, American-Bechtel, Inc., to further review and refine the CCATP, reevaluate the determination of system technology to be used in implementing the project, and conduct the necessary Environmental Impact Analysis of the resulting Transit Plan.

In June 1973, the CUTD commenced the first phase of the project, which included design criteria, specifications and general plans for the distributor subway, which was completed in 1974.

Following a public hearing in 1974, the CUTD submitted an Environmental Impact Analysis to the Federal government, and a revised application for a facilities grant for the Chicago Central Area Transit Project.

Each of the transit lines were examined to determine which segments would provide the earliest return on investment in terms of service to greatest need, and permit early integration into the existing CTA system.

No work was ever started on those elements because they were determined to be subject to more changeable circumstances and potential modification and, therefore, responsive to further study of demand and benefit as part of the continuing planning process.

Initially, the Core Plan, consisting essentially of the Franklin and Monroe Lines on specific alignments determined after extensive interagency studies and conferences in 1975 and 1976, was to be built first.

It would cross the Chicago River diagonally then curve under Franklin Street in the Central Business District in a stacked arrangement with stations and two continuous platforms (similar to the Red and Blue Line subways).

Lake Street "L" service was to continue operating over the remaining portion of the Union Loop "L" until some time later when financial arrangements permitted construction of the Monroe distributor subway, or at least until the Midway Line was built in 1993.

Cranes grappled with and lifted one car that had landed on its side in the street while viewers were held in suspense until word came that no pedestrians were caught beneath the 50,000 pound vehicle.

Even as CUTD staff commenced selecting engineers and contractors for the Franklin Line subway, a murmur of opposition began to be heard in Chicago, voices that questioned the wisdom of replacing the Union Loop "L".

In 1979, Chicago mayor Jane M. Byrne and Illinois governor James R. Thompson reached an agreement whereby the Franklin Street subway project, along with the Crosstown Expressway on the West Side, was to be canceled, the Union Loop Elevated (which by then had been placed on the National Register for Historic Places) retained and improved upon, and rapid transit developments for residential sections of Chicago where improvements were needed.

The Chicago Urban Transportation District, which had suffered from a lack of support and funding, was abolished by state legislation in 1984, and the remaining $12 million it had was transferred to the CTA.

By the 1980s and 1990s, replacement subways were deemed too expensive and extensions to the existing CTA heavy rail transit system were considered too limited in their benefits.

While no additional heavy rail rapid transit subways are planned for Chicago's Central Area because they are still deemed too high in construction costs and limited in their service potential, an east–west, cross-the-Loop rail system to link the Near West Side, Loop, and Near North Side communities, as well as Chicago's Union Station, Ogilvie Transportation Center, and Millennium Station (Metra Electric & South Shore Lines) is very possible.

Even with the Loop Link BRT in place and no available funding for such an endeavor ($478 million in 1969; around $3.3 billion today) seems likely, the Monroe Street distributor subway (Harrison/Morgan to Walton Place) could provide a more direct link serving the downtown Metra, Amtrak, and NICTD terminal stations (except LaSalle Street Station), and connect with all CTA rapid transit lines on the Loop Elevated, State, and Dearborn subways.

It could also provide better rail transportation to the University of Illinois at Chicago, Greektown, Millennium Park, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Navy Pier, and the North Michigan Avenue business district, as it was originally planned to do.