Given name

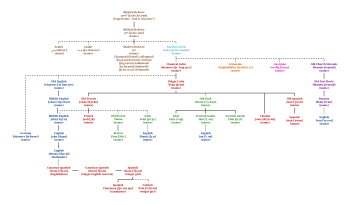

This order is also used to various degrees and in specific contexts in other European countries, such as Austria and adjacent areas of Germany (that is, Bavaria),[note 1] and in France, Switzerland, Belgium, Greece and Italy[citation needed], possibly because of the influence of bureaucracy, which commonly puts the family name before the given name.

The given name might also be used in compound form, as in, for example, John Paul or a hyphenated style like Bengt-Arne.

[3] Some double-given names for women were used at the start of the eighteenth century but were used together as a unit: Anna Maria, Mary Anne and Sarah Jane.

[5] In certain jurisdictions, a government-appointed registrar of births may refuse to register a name for the reasons that it may cause a child harm, that it is considered offensive, or if it is deemed impractical.

The most familiar example of this, to Western readers, is the use of Biblical and saints' names in most of the Christian countries (with Ethiopia, in which names were often ideals or abstractions—Haile Selassie, "power of the Trinity"; Haile Miriam, "power of Mary"—as the most conspicuous exception).

Similarly, the name Mary, now popular among Christians, particularly Roman Catholics, was considered too holy for secular use until about the 12th century.

Nonetheless, a number of popular characters commonly recur, including "Strong" (伟, Wěi), "Learned" (文, Wén), "Peaceful" (安, Ān), and "Beautiful" (美, Měi).

Despite China's increasing urbanization, several names such as "Pine" (松, Sōng) or "Plum" (梅, Méi) also still reference nature.

Instead, they may be selected to include particular sounds, tones, or radicals; to balance the Chinese elements of a child's birth chart; or to honor a generation poem handed down through the family for centuries.

[citation needed] Many female Japanese names end in -ko (子), usually meaning "child" on its own.

This is also true for Asian students at colleges in countries such as the United States, Canada, and Australia as well as among international businesspeople.

[citation needed] Most names in English are traditionally masculine (Hugo, James, Harold) or feminine (Daphne, Charlotte, Jane), but there are unisex names as well, such as Jordan, Jamie, Jesse, Morgan, Leslie/Lesley, Joe/Jo, Jackie, Pat, Dana, Alex, Chris/Kris, Randy/Randi, Lee, etc.

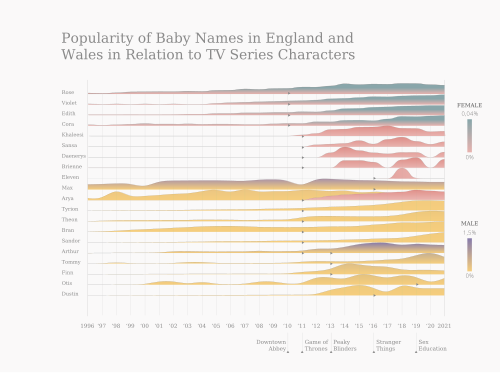

Not only have Mary and John gone out of favour in the English-speaking world, but the overall distribution of names has also changed significantly over the last 100 years for females, but not for males.

[33] Education, ethnicity, religion, class and political ideology affect parents' choice of names.

There are many tools parents can use to choose names, including books, websites and applications.

Newly famous celebrities and public figures may influence the popularity of names.

Notable examples include Pamela, invented by Sir Philip Sidney for a pivotal character in his epic prose work, The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia; Jessica, created by William Shakespeare in his play The Merchant of Venice; Vanessa, created by Jonathan Swift; Fiona, a character from James Macpherson's spurious cycle of Ossian poems; Wendy, an obscure name popularised by J. M. Barrie in his play Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up; and Madison, a character from the movie Splash.

Lara and Larissa were rare in America before the appearance of Doctor Zhivago, and have become fairly common since.

[37] Kayleigh became a particularly popular name in the United Kingdom following the release of a song by the British rock group Marillion.

For example, the given name Adolf has fallen out of use since the end of World War II in 1945.

Since the 1970s neologistic (creative, inventive) practices have become increasingly common and the subject of academic study.