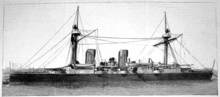

Chilean cruiser Esmeralda (1883)

The British shipbuilder Armstrong Mitchell constructed Esmeralda in the early 1880s, and the company's founder hailed the new ship as "the swiftest and most powerfully armed cruiser in the world".

During that conflict, Izumi contributed to the decisive Japanese victory in the Battle of Tsushima by being one of the first ships to make visual contact with the opposing Russian fleet.

[4] As historian Arne Røksund has said, "one of the fundamental ideas in the Jeune École's naval theory [was] that the weaker side should resort to alternative strategies and tactics, taking advantage of the possibilities opened up by technological progress.

"[7] To accomplish this, Jeune École adherents called for the construction of small, steam-powered, heavy-gunned, long-ranged, and higher-speed warships to counter the capital ship-heavy strategy of major navies and devastate their merchant shipping.

Esmeralda was the most capable of these ships, and although British neutrality meant that it could not be delivered until after the war's conclusion, the Chileans ordered it with the intention of gaining naval superiority over their neighbors.

[8][9] Esmeralda was designed by the British naval architect George Wightwick Rendel, who developed it from his plans for the earlier Japanese cruiser Tsukushi, laid down in 1879.

Armstrong boasted to press outlets in 1884 that Esmeralda was "the swiftest and most powerfully armed cruiser in the world" and that it was "almost absolutely secure from the worst effects of projectiles.

According to him, several cruisers could be built and sent out as commerce raiders, much like the Confederate States Navy warship Alabama during the American Civil War, all for the price of one ironclad.

With this comment, Armstrong hoped to induce the Royal Navy to order protected cruisers from his company to prevent him from selling them to British enemies.

His company added a weighty article in the Times of London that was anonymously written by Armstrong Mitchell's chief naval architect,[15][16] and the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, visited the ship.

[15] These marketing efforts proved quite successful: an 1885 article in The Steamship journal said that "no vessel of recent construction has attracted greater attention than the protected cruiser Esmeralda".

[15][18] Across the Atlantic, the Army and Navy Journal published an interview with an American naval officer who expressed his belief that Esmeralda could stand off San Francisco and drop shells into the city while being in no danger from the shorter-ranged shore-based batteries covering the Golden Gate strait.

[20] In Chile itself, Esmeralda's capabilities were highly anticipated: it was financed in part by public donations and the country's newspapers published lengthy treatises on the cruiser's potential power.

"[22] Like the Tsukushi design that preceded it, Esmeralda mounted a heavy armament and was constructed out of lightweight steel, a feature enabled by the Siemens process.

[15] It was also the fastest cruiser in the world upon its completion; had a better secondary armament; was able to steam longer distances before needing more coal; and had deck armor that extended the length of the ship to protect the propulsion machinery and magazines.

Moreover, the design of Esmeralda's coal bunkers meant that if it was hit in certain key areas, water would be able to flow into a large part of the ship.

[30][31] According to Rodger, Rendel gave Esmeralda large ten-inch (254 mm) guns and a high speed so its captain could choose an appropriate fighting range.

[33] Except for the designs which immediately followed Esmeralda (the Japanese Naniwa class and the Italian Giovanni Bausan), no other Armstrong-built protected cruiser would ever mount a gun larger than 8.2 inches (210 mm).

[35] For armament, Esmeralda's main battery was originally equipped with two ten-inch (254 mm)/30 caliber guns in two single barbettes, one each fore and aft.

[36] The propulsion machinery consisted of two horizontal compound steam engines built by R and W Hawthorn, which were fed by four double-ended fire-tube boilers.

[36] While the British government upheld its neutrality through the active prevention of warship deliveries to the countries involved in the War of the Pacific, Esmeralda was finished after the conclusion of the conflict and arrived in Chile on 16 October 1884.

[50][51] On 12 March, Esmeralda engaged in a prolonged chase of the steamer Imperial, an elusive transport ship that had a reputation for being the fastest on the coast, and had on occasion managed to bring reinforcements north for the Presidential cause.

Although Esmeralda was able to get close enough to fire shots at Imperial, the cruiser was unable to reach its maximum speed due to dirty boilers and lost track of the transport that night.

Their gunfire did not kill many soldiers, but it severely demoralized the Presidential forces; Scientific American stated that their shells "raised fearful havoc".

To get around this, the Chileans induced the Ecuadorian government to secretly act as an middleman by allegedly sending a considerable sum of money to Luis Cordero Crespo, the country's president.

[63] Although the Japanese purchased Esmeralda with the intention of using it in the First Sino-Japanese War, the cruiser arrived in Japan in February 1895—too late to take an active role in the conflict.

In December of that year, Izumi was deployed on a patrol line south of Dalian Bay after the Japanese cruiser Akashi struck a mine.

[76] After the Japanese victory, Izumi and the rest of the Sixth Division were deployed to support the invasion of Sakhalin by escorting the army's transport ships.

[71] For example, the same newspaper reported in February 1906 that the ship would transport former Prime Minister of Japan and the first Japanese Resident-General of Korea Itō Hirobumi to his post.