Chimpanzee genome project

[7] An analysis of the chimpanzee genome sequence was published in Nature on September 1, 2005, in an article produced by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, a group of scientists which is supported in part by the National Human Genome Research Institute, one of the National Institutes of Health.

Typical human and chimpanzee homologs of proteins differ in only an average of two amino acids.

As mentioned above, gene duplications are a major source of differences between human and chimpanzee genetic material, with about 2.7 percent of the genome now representing differences having been produced by gene duplications or deletions during approximately 6 million years [11] since humans and chimpanzees diverged from their common evolutionary ancestor.

[12] About 600 genes were identified that may have been undergoing strong positive selection in the human and chimpanzee lineages; many of these genes are involved in immune system defense against microbial disease (example: granulysin is protective against Mycobacterium tuberculosis [13]) or are targeted receptors of pathogenic microorganisms (example: Glycophorin C and Plasmodium falciparum).

[14] Another such region on chromosome 4 may contain elements regulating the expression of a nearby protocadherin gene that may be important for brain development and function.

Humans appear to have lost a functional Caspase 12 gene, which in other primates codes for an enzyme that may protect against Alzheimer's disease.

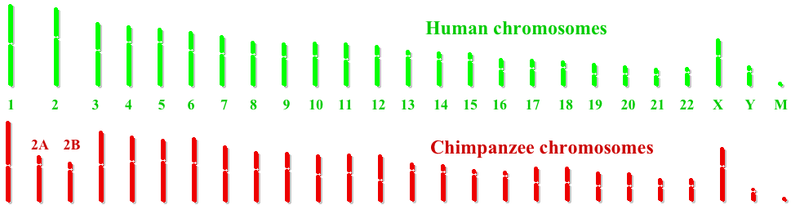

At the site of fusion, there are approximately 150,000 base pairs of sequence not found in chimpanzee chromosomes 2A and 2B.

Additional linked copies of the PGML/FOXD/CBWD genes exist elsewhere in the human genome, particularly near the p end of chromosome 9.

This suggests that a copy of these genes may have been added to the end of the ancestral 2A or 2B prior to the fusion event.