Chinese creation myths

For example, creation from chaos (Chinese Hundun and Hawaiian Kumulipo), dismembered corpses of a primordial being (Pangu, Indo-European Yemo and Mesopotamian Tiamat), world parent siblings (Fuxi and Nüwa and Japanese Izanagi and Izanami), and dualistic cosmology (yin and yang and Zoroastrian Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu).

Anne Birrell explains[1] that qi "was believed to embody cosmic energy governing matter, time, and space.

The Tao Te Ching, written sometime before the 4th century BC, suggests a less mystical Chinese cosmogony and has some of the earliest allusions to creation.

Birrell calls it "the most valuable document in Chinese mythography" and surmises an earlier date for its mythos "since it clearly draws on a preexisting fund of myths.

From the "formless expanse" the primeval element of misty vapor emerges spontaneously as a creative force, which is organically constructed as a set of binary forces in opposition to each other — upper and lower spheres, darkness and light, Yin and Yang — whose mysterious transformations bring about the ordering of the universe.".

The Daoyuan (道原, "Origins of the Tao") is one of the Huangdi Sijing manuscripts discovered in 1973 among the Mawangdui Silk Texts excavated from a tomb dated to 168 BC.

[9] The 4th or 3rd century BC Taiyi Shengshui ("Great One Giving Birth to Water"), a Taoist text excavated in 1993 as part of the Guodian Chu Slips, seems to offer its own unique creation myth, but analysis remains uncertain.

The 139 BC Huainanzi, an eclectic text compiled under the direction of the Han prince Liu An, contains two cosmogonic myths that develop the dualistic concept of Yin and Yang: When Heaven and Earth were yet unformed, all was ascending and flying, diving and delving.

[11]Birrell suggests this abstract Yin-Yang dualism between the two primeval spirits or gods may be the "vestige of a much older mythological paradigm that was then rationalized and diminished", comparable to the Akkadian Enûma Eliš creation myth of Abzu and Tiamat, male fresh water and female salt water.

[12] The Lingxian (靈憲), written around AD 120 by the polymath Zhang Heng, thoroughly accounts for the creation of Heaven and Earth.

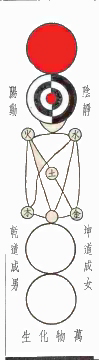

[13]The Neo-Confucianist philosopher Zhou Dunyi provided a multifaceted cosmology in his Taiji Tushuo (太極圖說, "Diagram Explaining the Supreme Ultimate"), which integrated the I Ching with Taoism and Chinese Buddhism.

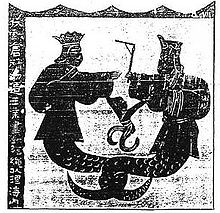

In Chinese mythology, the goddess Nüwa repaired the fallen pillars holding up the sky, creating human beings either before or after.

The ancient Chinese believed in a square earth and a round, domelike sky supported by eight giant pillars (cf.

The "Heavenly Questions" of the Songs of Chu from around the 4th century BC is the first surviving text that refers to Nüwa: "By what law was Nü Wa raised up to become high lord?

"[14] Two Huainanzi chapters record Nüwa mythology two centuries later: Going back to more ancient times, the four [of 8] pillars were broken; the nine provinces were in tatters.

Fires blazed out of control and could not be extinguished; water flooded in great expanses and would not recede.

Thereupon, Nüwa smelted together five-colored stones in order to patch up the azure sky, cut off the legs of the great turtle to set them up as the four pillars, killed the black dragon to provide relief for Ji Province, and piled up reeds and cinders to stop the surging waters.

The azure sky was patched; the four pillars were set up; the surging waters were drained; the province of Ji was tranquil; crafty vermin died off; blameless people [preserved their] lives.

Bearing the square [nine] provinces on her back and embracing Heaven, [Fuxi and Nüwa established] the harmony of spring and the yang of summer, the slaughtering of autumn and the restraint of winter.

The commentary of Xu Shen written around AD 100 says "seventy transformations" refers to Nuwa's power to create everything in the world.

The Fengsu Tongyi ("Common Meanings in Customs"), written by Ying Shao around AD 195, describes Han-era beliefs about the primeval goddess.

Though she worked feverishly, she did not have enough strength to finish her task, so she drew her cord in a furrow through the mud and lifted it out to make human beings.

The 9th-century Duyi Zhi (獨異志, "A Treatise on Extraordinary Things") by Li Rong records a later tradition that Nüwa and her brother Fuxi were the first humans.

So the brother at once went with his sister up Mount K'un-lun and made this prayer: "Oh Heaven, if Thou wouldst send us two forth as man and wife, then make all the misty vapor gather.

[18]One of the most popular creation myths in Chinese mythology describes the first-born semidivine human Pangu (盤古, "Coiled Antiquity") separating the world egg-like Hundun (混沌, "primordial chaos") into Heaven and Earth.

[21] Like the Sanwu Liji, the Wuyun Linian Ji (五遠歷年紀, "A Chronicle of the Five Cycles of Time") is another 3rd-century text attributed to Xu Zheng.

[22]Lincoln found parallels between Pangu and the Indo-European world parent myth, such as the primeval being's flesh becoming earth and hair becoming plants.

On the one hand, With regard to China there is the very real problem of the extreme paucity and fragmentation of mythological accounts, an almost total absence of any coherent mythic narratives dating to the early periods of Chinese culture.

This is even more true with respect to authentic cosmogonic myths, since the preserved fragments are extremely meager and in most cases are secondary accounts historicized and moralized by the redactors of the Confucian school that was emerging as the predominant classical tradition during the Former Han period.

The biographies of the ancient heroes of China contain numerous mythic elements; but no cosmogonic theme has entered into the literature without having undergone a transformation.