1740 Batavia massacre

It was carried out by European soldiers of the Dutch East India Company and allied members of other Batavian ethnic groups.

In September 1740, as unrest rose among the Chinese population, spurred by government repression and declining sugar prices, Governor-General Adriaan Valckenier declared that any uprising would be met with deadly force.

During the early years of the Dutch colonisation of the East Indies (modern-day Indonesia), many people of Chinese descent were contracted as skilled artisans in the construction of Batavia on the northwestern coast of Java;[2] they also served as traders, sugar mill workers, and shopkeepers.

[3] The economic boom, precipitated by trade between the East Indies and China via the port of Batavia, increased Chinese immigration to Java.

[5] The deportation policy was tightened during the 1730s, after an outbreak of malaria killed thousands, including the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, Dirck van Cloon.

[6] As a result, Commissioner of Native Affairs Roy Ferdinand, under orders of Governor-General Adriaan Valckenier, decreed on 25 July 1740, that Chinese considered suspicious would be deported to Ceylon (modern day Sri Lanka) and forced to harvest cinnamon.

Economic factors played a role: most natives were poor, and perceived the Chinese as occupying some of the most prosperous neighbourhoods in the city.

[13][14] Although the Dutch historian Albertus Nicolaas Paasman [nl] notes that at the time the Chinese were the "Jews of Asia",[8] the actual situation was more complicated.

[20] Initially some members of the Council of the Indies (Raad van Indië) believed that the Chinese would never attack Batavia,[10] and stronger measures to control the Chinese were blocked by a faction led by Valckenier's political opponent, the former governor of Zeylan Gustaaf Willem van Imhoff, who returned to Batavia in 1738.

[7] On the evening of 1 October Valckenier received reports that a crowd of a thousand Chinese had gathered outside the gate, angered by his statements at the emergency meeting five days earlier.

[7][25] Two groups of 50 Europeans and some native porters were sent to outposts on the south and east sides of the city,[26] and a plan of attack was formulated.

[6][11] In response, the Dutch sent 1,800 regular troops, accompanied by schutterij (militia) and eleven battalions of conscripts to stop the revolt; they established a curfew and cancelled plans for a Chinese festival.

[6] Fearing that the Chinese would conspire against the colonials by candlelight, those inside the city walls were forbidden to light candles and were forced to surrender everything "down to the smallest kitchen knife".

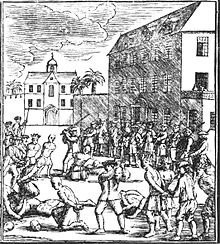

[7][31] Meanwhile, rumors spread among the other ethnic groups in Batavia, including slaves from Bali and Sulawesi, Bugis, and Balinese troops, that the Chinese were plotting to kill, rape, or enslave them.

The Dutch politician and critic of colonialism W. R. van Hoëvell wrote that "pregnant and nursing women, children, and trembling old men fell on the sword.

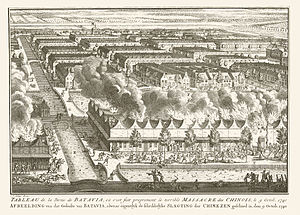

[38] Attempts to extinguish fires in areas devastated the preceding day failed, and the flames increased in vigour, and continued until 12 October.

[42] Two days later the council established a reward of two ducats for every Chinese head surrendered to the soldiers as an incentive for the other ethnic groups to assist in the purge.

On October 25, after almost two weeks of minor skirmishes, 500 armed Chinese approached Cadouwang (now Angke), but were repelled by cavalry under the command of Ritmeester Christoffel Moll and Cornets Daniel Chits and Pieter Donker.

[44] Fearful of the oncoming Dutch, the Chinese retreated to a sugar mill in Kampung Melayu, four hours from Salapadjang; this stronghold fell to troops under Captain Jan George Crummel.

[50] The Indonesian historian Benny G. Setiono notes that 500 prisoners and hospital patients were killed,[48] and a total of 3,431 people survived.

[52] As part of conditions for the cessation of violence, all of Batavia's ethnic Chinese were moved to a pecinan, or Chinatown, outside of the city walls, now known as Glodok.

[4] Other ethnic Chinese led by Khe Pandjang[40] fled to Central Java where they attacked Dutch trading posts, and were later joined by troops under the command of the Javanese sultan of Mataram, Pakubuwono II.

[3] On 6 December 1740, van Imhoff and two fellow councillors were arrested on the orders of Valckenier for insubordination, and on 13 January 1741, they were sent to the Netherlands on separate ships;[56][57] they arrived on 19 September 1741.

On 25 January 1742, he arrived in Cape Town but was detained, and investigated by governor Hendrik Swellengrebel by order of the Lords XVII.

[16] After the 1740 massacre, it became apparent over the ensuing decades through a series of considerations that Batavia needed Chinese people for a long list of trades.

[78][79] The name Rawa Bangke, for a subdistrict of East Jakarta, may be derived from the colloquial Indonesian word for corpse, bangkai, due to the great number of ethnic Chinese killed there; a similar etymology has been suggested for Angke in Tambora.