Ojibwe

: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: Ojibweg ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (Ojibwewaki ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ)[3] covers much of the Great Lakes region and the northern plains, extending into the subarctic and throughout the northeastern woodlands.

The Ojibwe are part of the Council of Three Fires (along with the Odawa and Potawatomi) and of the larger Anishinaabeg, which includes Algonquin, Nipissing, and Oji-Cree people.

[6] Their Midewiwin Society is well respected as the keeper of detailed and complex scrolls of events, oral history, songs, maps, memories, stories, geometry, and mathematics.

Its sister languages include Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Cree, Fox, Menominee, Potawatomi, and Shawnee among the northern Plains tribes.

[17] They traded widely across the continent for thousands of years as they migrated, and knew of the canoe routes to move north, west to east, and then south in the Americas.

The five original Anishinaabe doodem were the Wawaazisii (Bullhead), Baswenaazhi (Echo-maker, i.e., Crane), Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck), Nooke (Tender, i.e., Bear) and Moozoonsii (Little Moose).

Their second major settlement, referred to as their "seventh stopping place", was at Shaugawaumikong (or Zhaagawaamikong, French, Chequamegon) on the southern shore of Lake Superior, near the present La Pointe, Wisconsin.

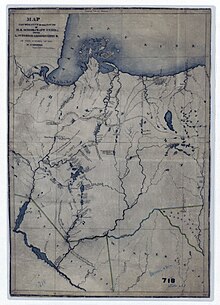

By the end of the 18th century, the Ojibwe controlled nearly all of present-day Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and Minnesota, including most of the Red River area.

They also controlled the entire northern shores of lakes Huron and Superior on the Canadian side and extending westward to the Turtle Mountains of North Dakota.

Together they launched a massive counterattack against the Iroquois and drove them out of Michigan and southern Ontario until they were forced to flee back to their original homeland in upstate New York.

In 1745, they adopted guns from the British in order to repel the Dakota people in the Lake Superior area, pushing them to the south and west.

[22] After losing the war in 1763, France was forced to cede its colonial claims to lands in Canada and east of the Mississippi River to Britain.

[citation needed] In the Sandy Lake Tragedy, several hundred Ojibwe died because of the federal government's failure to deliver fall annuity payments.

Through the efforts of Chief Buffalo and the rise of popular opinion in the U.S. against Ojibwe removal, the bands east of the Mississippi were allowed to return to reservations on ceded territory.

In British North America, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 following the Seven Years' War governed the cession of land by treaty or purchase.

As it was still preoccupied by war with France, Great Britain ceded to the United States much of the lands in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, parts of Illinois and Wisconsin, and northern Minnesota and North Dakota to settle the boundary of their holdings in Canada.

The battle took place along the Brule River (Bois Brûlé) in what is today northern Wisconsin and resulted in a decisive victory for the Ojibwe.

From the 1870s to 1938, the Grand General Indian Council of Ontario attempted to reconcile multiple traditional models into one cohesive voice to exercise political influence over colonial legislation.

Most Ojibwe, except for the Great Plains bands, have historically lived a settled (as opposed to nomadic) lifestyle, relying on fishing and hunting to supplement the cultivation of numerous varieties of maize and squash, and the harvesting of manoomin (wild rice) for food.

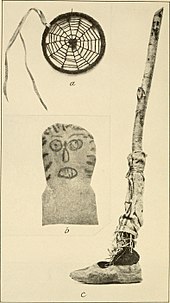

They have a culturally-specific form of pictorial writing, used in the religious rites of the Midewiwin and recorded on birch bark scrolls and possibly on rock.

Petroforms and medicine wheels have been used to teach important spiritual concepts, record astronomical events, and to use as a mnemonic device for certain stories and beliefs.

During the summer months, the people attend jiingotamog for the spiritual and niimi'idimaa for a social gathering (powwows) at various reservations in the Anishinaabe-Aki (Anishinaabe Country).

Both Plains and Woodlands Ojibwe claim the earliest form of dark cloth dresses decorated with rows of tin cones - often made from the lids of tobacco cans- that make a jingling sound when worn by the dancer.

In the United States, many Ojibwe communities safe-guard their burial mounds through the enforcement of the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

They grew beans, squash, corn and potatoes and foraged for blueberries, blackberries, choke cherries, raspberries, gooseberries and huckleberries.

"[31] The five original totems were Wawaazisii (Bullhead), Baswenaazhi/"Ajiijaak" ("Echo-maker", i.e., Crane), Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck), Nooke ("Tender", i.e., Bear) and Moozwaanowe ("Little" Moose-tail).

The Crane totem was the most vocal among the Ojibwe, and the Bear was the largest – so large, that it was sub-divided into body parts such as the head, the ribs and the feet.

If burial preparations could not be completed the day of the death, guests and medicine men were required to stay with the deceased and the family in order to help mourn, while also singing songs and dancing throughout the night.

[35] Plants used by the Ojibwe include Agrimonia gryposepala, used for urinary problems,[38] and Pinus strobus, the resin of which was used to treat infections and gangrene.

[45] The Ojibwe eat the corms of Sagittaria cuneata for indigestion, and also as a food, eaten boiled fresh, dried or candied with maple sugar.