Choral symphony

Notable works in the genre were produced in the 20th century by Gustav Mahler, Igor Stravinsky, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Benjamin Britten and Dmitri Shostakovich, among others.

[4] The term "choral symphony" indicates the composer's intention that the work be symphonic, even with its fusion of narrative or dramatic elements that stems from the inclusion of words.

The text often determines the basic symphonic outline, while the orchestra's role in conveying the musical ideas is similar in importance to that of the chorus and soloists.

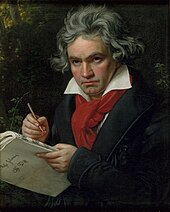

[7] As the symphony grew in size and artistic significance, thanks in part to efforts in the form by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert it also amassed greater prestige.

[11] Liszt wrote two choral symphonies, following in these multi-movement forms the same compositional practices and programmatic goals he had established in his symphonic poems.

[11] More than a century later, Henryk Górecki's Second Symphony, subtitled "Copernican", was commissioned in 1973 by the Kosciuszko Foundation in New York to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus.

[25] Tan Dun's Symphony 1997: Heaven Earth Mankind commemorated the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong that year to the People's Republic of China.

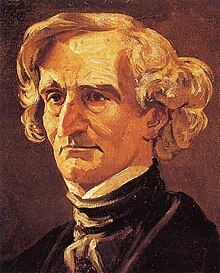

There, Berlioz allows the orchestra to express the majority of the drama in instrumental music and saves words for expository and narrative sections of the work.

The composer writes, "The plan of the work is symphonic rather than narrative or dramatic, and this may be held to justify the frequent repetition of important words and phrases which occur in the poem.

Mahler took a similar, perhaps even more radical approach in his Eighth Symphony, presenting many lines of the first part, "Veni, Creator Spiritus", in what music writer and critic Michael Steinberg referred to as "an incredibly dense growth of repetitions, combinations, inversions, transpositions and conflations".

Vaughan Williams uses a chorus of women's voices wordlessly in his Sinfonia Antartica, based on his music for the film Scott of the Antarctic, to help set the bleakness of the overall atmosphere.

Throughout this section, according to music writer Michael Kennedy, Mahler displays considerable mastery in manipulating multiple independent melodic voices.

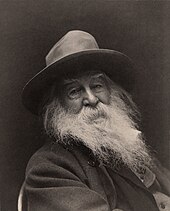

"[46] In his Leaves of Grass: A Choral Symphony, Robert Strassburg composed a symphonic "musical setting" in ten movements for the poetry of Walt Whitman while balancing the contributions of a narrator, a chorus and an orchestra.

[47] Discovering three other Yevtushenko poems in the poet's collection Vzmakh ruki (A Wave of the Hand) prompted him to proceed to a full-length choral symphony, with "A Career" as the closing movement.

Musicologist Francis Maes comments that Shostakovich did so by complementing Babi Yar's theme of Jewish suffering with Yevtushenko's verses about other Soviet abuses:[47] "'At the Store' is a tribute to the women who have to stand in line for hours to buy the most basic foods,... 'Fears' evokes the terror under Stalin.

Havergal Brian allowed the form of his Fourth Symphony, subtitled "Das Siegeslied" (Psalm of Victory), to be dictated by the three-part structure of his text, Psalm 68; the setting of Verses 13–18 for soprano solo and orchestra forms a quiet interlude between two wilder, highly chromatic martial ones set for massive choral and orchestral forces.

[48][49] Likewise, Szymanowski allowed the text by 13th-century Persian poet Rumi to dictate what Jim Samson calls the "single tripartite movement"[50] and "overall arch structure"[51] of his Third Symphony, subtitled "Song of the Night".

To hear the different parts of the choir describing in word and tone "laughter" and "tears" respectively at the same time is to realize how little the possibilities of choral singing have as yet been grasped by the ordinary conductor and composer.

[61] Penderecki's Seventh Symphony of 1996, subtitled "Seven Gates of Jerusalem" and originally conceived as an oratorio, is not only written in seven movements but, musicologist Richard Whitehouse writes, is "pervaded by the number 'seven' at various levels.

Any man or woman who aspires to be a 'Person of Knowledge' will, through arduous training and effort, have to encounter the Blue Deer...."[37] Addition of a text can effectively change the programmatic intent of a composition, as with the two choral symphonies of Franz Liszt.

[64] According to Shulstad, "Liszt's original version of 1854 ended with a last fleeting reference to Gretchen and an ... orchestral peroration in C major, based on the most majestic of themes from the opening movement.

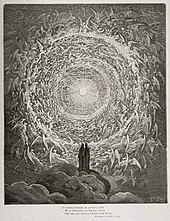

[66] This action, Searle claims, effectively destroyed the work's formal balance and left the listener, like Dante, to gaze upward at the heights of Heaven and hear its music from afar.

[69] While the Ninth Psalm's theme conveyed Shostakovich's outrage over Stalin's oppression,[70] a public performance of a work with such a text would have been impossible before the German invasion.

[32] He wrote in his preface to Roméo: If, in the famous garden and cemetery scenes the dialogue of the two lovers, Juliet's asides, and Romeo's passionate outbursts are not sung, if the duets of love and despair are given to the orchestra, the reasons are numerous and easy to comprehend.

It is also because the very sublimity of this love made its depiction so dangerous for the musician that he had to give his imagination a latitude that the positive sense of the sung words would not have given him, resorting instead to instrumental language, which is richer, more varied, less precise, and by its very indefiniteness incomparably more powerful in such a case.

[73] Musicologist Hugh Macdonald writes that as Berlioz kept the idea of symphonic construction closely in mind, he allowed the orchestra to express the majority of the drama in instrumental music and set expository and narrative sections in words.

[76] Despite the resulting stylistic disparity, biographer Alexander Ivashkin comments, "musically almost all these sections blend the choral [sic] tune and subsequent extensive orchestral 'commentary.

[76] The program in Schnittke's Fourth Symphony, reflecting the composer's own religious dilemma at the time it was written,[78] is more complex in execution, with the majority of it expressed wordlessly.

In the 22 variations that make up the symphony's single movement,[b] Schnittke enacts the 15 traditional Mysteries of the Rosary, which highlight important moments in the life of Christ.

[78] The programmatic intent of using these different types of music, Ivashkin writes, is an insistence by the composer "on the idea ... of the unity of humanity, a synthesis and harmony among various manifestations of belief".