God in Christianity

[16] The theology of the attributes and nature of God has been discussed since the earliest days of Christianity, with Irenaeus writing in the 2nd century: "His greatness lacks nothing, but contains all things".

[25][26] Although the New Testament does not have a formal doctrine of the Trinity as such, "it does repeatedly speak of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit... in such a way as to compel a Trinitarian understanding of God".

[48] Eastern creeds (those known to have come from a later date) began with an affirmation of faith in "one God" and almost always expanded this by adding "the Father Almighty, Maker of all things visible and invisible" or words to that effect.

[48] Augustine of Hippo, Thomas Aquinas, and other Christian theologians have described God with the Latin term ipsum esse, a phrase that translates roughly to "being itself".

As time passed, theologians and philosophers developed more precise understandings of the nature of God and began to produce systematic lists of his attributes.

[57][58] When reading the Hebrew Bible aloud, Jews replace the Tetragrammaton with the title Adonai, translated as Kyrios in the Septuagint and the Greek New Testament.

In the 2nd century, Irenaeus addressed the issue and expounded on some attributes; for example, Book IV, chapter 19 of Against Heresies[71] states: "His greatness lacks nothing, but contains all things".

[22] In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas focused on a shorter list of just eight attributes, namely simplicity, perfection, goodness, incomprehensibility, omnipresence, immutability, eternity and oneness.

[56] Hick suggests that when listing the attributes of God, the starting point should be his self-existence ("aseity") which implies his eternal and unconditioned nature.

For instance, while the eighty second canon of the Council of Trullo in 692 did not specifically condemn images of the Father, it suggested that icons of Christ were preferred over Old Testament shadows and figures.

The Second Council of Nicaea in 787 effectively ended the first period of Byzantine iconoclasm and restored the honouring of icons and holy images in general.

For as through the language of the words contained in this book all can reach salvation, so, due to the action which these images exercise by their colors, all wise and simple alike, can derive profit from them.

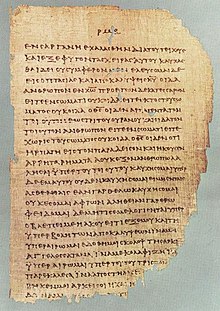

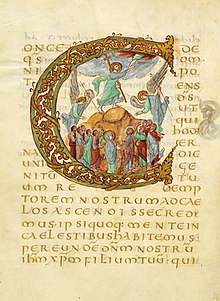

[91] By the 12th century depictions of God the Father had started to appear in French illuminated manuscripts, which as a less public form could often be more adventurous in their iconography, and in stained glass church windows in England.

Gradually the amount of the human symbol shown can increase to a half-length figure, then a full-length, usually enthroned, as in Giotto's fresco of c. 1305 in Padua.

In the Catholic Church, the pressure to restrain religious imagery resulted in the highly influential decrees of the final session of the Council of Trent in 1563.

In some of these paintings the Trinity is still alluded to in terms of three angels, but Giovanni Battista Fiammeri also depicted God the Father as a man riding on a cloud, above the scenes.

In 1632 most members of the Star Chamber court in England (except the Archbishop of York) condemned the use of the images of the Trinity in church windows, and some considered them illegal.

[102] Later in the 17th century Sir Thomas Browne wrote that he considered the representation of God the Father using an old man "a dangerous act" that might lead to, in his words, "Egyptian symbolism".

[103] In 1847, Charles Winston was still critical of such images as a "Romish trend" (a derisive term used to refer to Roman Catholics) that he considered best avoided in England.

[111] These diverging interpretations have since given rise to a good number of variants, with various scholars proposing new eschatological models that borrow elements from these.

[118][119] Since the 1st century, Christians have called upon God with the name "Father, Son and Holy Spirit" in prayer, baptism, communion, exorcism, hymn-singing, preaching, confession, absolution and benediction.

[32][33] The New Testament includes a number of the usages of the three-fold liturgical and doxological formula, e.g., 2 Corinthians 1:21–22 stating: "he that establisheth us with you in Christ, and anointed us, is God; who also sealed us, and gave [us] the earnest of the Spirit in our hearts".

[121] The general concept was expressed in early writings from the beginning of the 2nd century forward, with Irenaeus writing in his Against Heresies (Book I Chapter X):[118] Around AD 213 in Adversus Praxeas (chapter 3) Tertullian provided a formal representation of the concept of the Trinity, i.e., that God exists as one "substance" but three "Persons": The Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.

[124][125] Bernhard Lohse (1928–1997) states that the doctrine of the Trinity does not go back to non-Christian sources such as Plato or Hinduism and that all attempts at suggesting such connections have floundered.

[37][128][129] The 20th century witnessed an increased theological focus on the doctrine of the Trinity, partly due to the efforts of Karl Barth in his four volume Church Dogmatics.

[149] The core Christian belief is that through the death and resurrection of Jesus, sinful humans can be reconciled to God and thereby are offered salvation and the promise of eternal life.

[150] The belief in the redemptive nature of Jesus' death predates the Pauline letters and goes back to the earliest days of Christianity and the Jerusalem church.

[148][156][157][158] More recently, discussions of the theological issues related to God the Son and its role in the Trinity were addressed in the 20th century in the context of a "Trinity-based" perspective on divine revelation.

[172] Most Protestant denominations and other traditions arising since the Reformation hold general Trinitarian beliefs and theology regarding God the Father similar to that of Roman Catholicism.

This includes churches arising from Anabaptism, Anglicanism, Baptist, Lutheranism, Methodism, Moravianim, Plymouth Brethren, Quakerism and Reformed Christianity.