Hand of God (art)

The hand, sometimes including a portion of an arm, or ending about the wrist, is used to indicate the intervention in or approval of affairs on Earth by God, and sometimes as a subject in itself.

The Hand is seen appearing from above in a fairly restricted number of narrative contexts, often in a blessing gesture (in Christian examples), but sometimes performing an action.

[4] In the art of the Amarna period in Egypt under Akhenaten, the rays of the Aten sun-disk end in small hands to suggest the bounty of the supreme deity.

[5] There are numerous references to the hand, or arm, of God in the Hebrew Bible, most clearly metaphorical in the way that remains current in modern English, but some capable of a literal interpretation.

References to the hand of God occur numerous times in the Pentateuch alone, particularly in regards to the unfolding narrative of the Israelites' exodus from Egypt (cf.

For example, when Stephen is filled with the "holy spirit" he looks to heaven and sees Jesus standing by the right hand of God (Acts 7:55).

In Christian art, the hand of God has traditionally been understood as an artistic metaphor that is not intended to indicate that the deity was physically present or seen in any subject depicted.

In the late antique and early medieval periods, the representation of the full-bodied figure of God the Father would have been considered a grave violation of the Second Commandment.

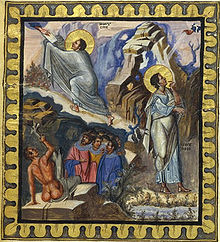

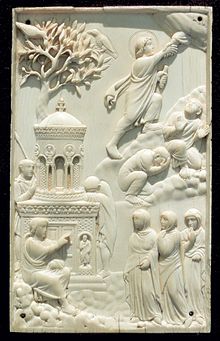

[12] In early Christian and Byzantine art, the hand of God is seen appearing from above in a fairly restricted number of narrative contexts, often in a blessing gesture, but sometimes performing an action.

Especially in Roman mosaics, but also in some German imperial commissions, for example on the Lothair Cross, the hand is clenched around a wreath that goes upwards, and behind which the arm then disappears, forming a tidy circular motif.

[26] This theme is not then seen in Byzantine art until the late 10th century, when it appears in coins of John I Tzimisces (969–976), long after it was common in the West.

This looser usage of the motif reaches its peak in Romanesque art, where it occasionally appears in all sorts of contexts – indicating the "right" speaker in a miniature of a disputation, or as the only decoration at the top of a monastic charter.

[30] The hand occasionally appears in Western Annunciations, even as late as Simone Martini in the 14th century, by which time the dove, sometimes accompanied by a small image of God the Father, has become more common.

[31] The hand appears at the top of a number of Late Antique apse mosaics in Rome and Ravenna, above a variety of compositions that feature either Christ or the cross,[f] some covered by the regular contexts mentioned above, but others not.

From the 14th century, and earlier in some contexts, full figures of God the Father became increasingly common in Western art, though still controversial and rare in the Orthodox world.

The motif did not disappear in later iconography, and enjoyed a revival in the 15th century as the range of religious subjects greatly expanded and depiction of God the Father became controversial again among Protestants.

In a high Rococo setting at the Windberg Abbey, Lower Bavaria, the Hand of God holds scales in which a lily stem indicating Saint Catherine's purity outweighs the crown and sceptre of worldly pomp.

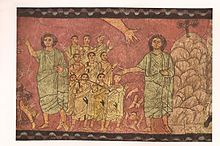

[32] In the Dura Europos synagogue, the hand of God appears ten times, in five out of the twenty-nine biblically themed wall paintings including the Binding of Isaac, Moses and the Burning Bush, Exodus and Crossing of the Red Sea, Elijah Reviving the Child of the Widow of Zarepheth, and Ezekiel in the Valley of Dry Bones.

In the Susiya synagogue, the hand of God appears on the defaced remains of a marble bimah screen that perhaps once illustrated a biblical scene such as Moses Receiving the Law or the Binding of Isaac.