Christian mythology

The term has also been applied to modern stories revolving around Christian themes and motifs, such as the writings of C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Madeleine L'Engle, and George MacDonald.

By the time of Christ, muthos had started to take on the connotations of "fable, fiction,"[4] and early Christian writers often avoided calling a story from canonical scripture a "myth".

Folklorists define folktales (in contrast to "true" myths) as stories that are considered purely fictitious by their tellers and that often lack a specific setting in space or time.

[30] The Zoroastrian concepts of Ahriman, Amesha Spentas, Yazatas, and Daevas probably gave rise to the Christian understanding of Satan, archangels, angels, and demons.

[39] According to a tradition preserved in Eastern Christian folklore, Golgotha was the summit of the cosmic mountain at the center of the world and the location where Adam had been both created and buried.

[41][42] George Every discusses the connection between the cosmic center and Golgotha in his book Christian Mythology, noting that the image of Adam's skull beneath the cross appears in many medieval representations of the crucifixion.

[39] Many Near Eastern religions include a story about a battle between a divine being and a dragon or other monster representing chaos—a theme found, for example, in the Enuma Elish.

[43][44][45] A number of scholars have argued that the ancient Israelites incorporated the combat myth into their religious imagery, such as the figures of Leviathan and Rahab,[46][47] the Song of the Sea,[46] Isaiah 51:9–10's description of God's deliverance of his people from Babylon,[46] and the portrayals of enemies such as Pharaoh and Nebuchadnezzar.

[53][54][55] An important study of this figure is James George Frazer's The Golden Bough, which traces the dying God theme through a large number of myths.

[53][59] In the article "Dying God" in The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, David Leeming notes that Christ can be seen as bringing fertility, though of a spiritual as opposed to physical kind.

[68] An example from the Late Middle Ages comes from Dieudonné de Gozon, third Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes, famous for slaying the dragon of Malpasso.

[...] In other words, by the simple fact that he was regarded as a hero, de Gozon was identified with a category, an archetype, which [...] equipped him with a mythical biography from which it was impossible to omit combat with a reptilian monster.

According to this story, Christ descended into the land of the dead after his crucifixion, rescuing the righteous souls that had been cut off from heaven due to the taint of original sin.

Eschatological myths would also include the prophesies of end of the world and a new millennium in the Book of Revelation, and the story that Jesus will return to earth some day.

Much of the Old Testament does not express a belief in a personal afterlife of reward or punishment:"All the dead go down to Sheol, and there they lie in sleep together–whether good or evil, rich or poor, slave or free (Job 3:11–19).

"[79] Later Old Testament writings, particularly the works of the Hebrew prophets, describe a final resurrection of the dead, often accompanied by spiritual rewards and punishments:"Many who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake.

But the wise shall shine brightly like the splendor of the firmament, and those who lead the many to justice shall be like the stars forever" (Daniel 12:2).However, even here, the emphasis is not on an immediate afterlife in heaven or hell, but rather on a future bodily resurrection.

Dante's three-part Divine Comedy is a prime example of such afterlife mythology, describing Hell (in Inferno), Purgatory (in Purgatorio), and Heaven (in Paradiso).

According to Matthew's gospel, when Jesus is on trial before the Roman and Jewish authorities, he claims, "In the future you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Mighty One and coming on the clouds of heaven.

Theologian Martin Delrio was one of the first to provide a vivid description in his influential Disquisitiones magicae:[103] There, on most occasions, once a foul, disgusting fire has been lit, an evil spirit sits on a throne as president of the assembly.

[116] Neil Forsyth writes that "what distinguishes both Jewish and Christian religious systems […] is that they elevate to the sacred status of myth narratives that are situated in historical time".

[124] In The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, David Leeming claims that Judeo-Christian messianic ideas have influenced 20th-century totalitarian systems, citing the state ideology of the Soviet Union as an example.

[127] A distinctive characteristic of the Hebrew Bible is the reinterpretation of myth on the basis of history, as in the Book of Daniel, a record of the experience of the Jews of the Second Temple period under foreign rule, presented as a prophecy of future events and expressed in terms of "mythic structures" with "the Hellenistic kingdom figured as a terrifying monster that cannot but recall [the Near Eastern pagan myth of] the dragon of chaos".

[151][citation needed] The official text repeated by the attendees during Roman Catholic mass (the Apostles' Creed) contains the words "He ascended into Heaven, and is Seated at the Right Hand of God, The Father.

[159] The medieval trouveres developed a "mythology of woman and Love" which incorporated Christian elements but, in some cases, ran contrary to official church teaching.

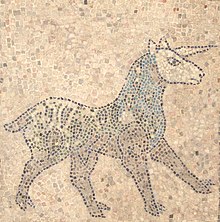

[160][161] According to Every, one example may be "the myth of St. George" and other stories about saints battling dragons, which were "modelled no doubt in many cases on older representations of the creator and preserver of the world in combat with chaos".

[159] According to Lorena Laura Stookey, "many scholars" see a link between stories in "Irish-Celtic mythology" about journeys to the Otherworld in search of a cauldron of rejuvenation and medieval accounts of the quest for the Holy Grail.

[164] These eschatological myths appeared "in the Crusades, in the movements of a Tanchelm and an Eudes de l'Etoile, in the elevation of Fredrick II to the rank of Messiah, and in many other collective messianic, utopian, and prerevolutionary phenomena".

[122] During the Renaissance, there arose a critical attitude that sharply distinguished between apostolic tradition and what George Every calls "subsidiary mythology"—popular legends surrounding saints, relics, the cross, etc.—suppressing the latter.

[166] An example is John Milton's Paradise Lost, an "epic elaboration of the Judeo-Christian mythology" and also a "veritable encyclopedia of myths from the Greek and Roman tradition".