Christian views on poverty and wealth

[1] Scottish theologian Jack Mahoney has characterized the sayings of Jesus in Mark 10:23–27[2] as having "imprinted themselves so deeply on the Christian community through the centuries that those who are well off, or even comfortably off, often feel uneasy and troubled in conscience.

Miller cites Paul's observation in 1st Timothy that, "people who want to get rich fall into temptation and a trap and into many foolish and harmful desires that plunge men into ruin and destruction.

"Kahan cites Jesus' injunction against amassing material wealth as an example that the "good [Christian] life was one of poverty and charity, storing up treasures in heaven instead of earth.

[14] Kahan argues that Christianity is unique because it sparked the beginning of a phenomenon which he calls the "Great Renunciation" in which "millions of people would renounce sex and money in God's name.

For example, the Franciscan orders have traditionally foregone all individual and corporate forms of ownership; in another example, the Catholic Worker Movement advocates voluntary poverty.

Most teachers of prosperity theology maintain that a combination of faith, positive speech, and donations to specific Christian ministries will always cause an increase in material wealth for those who practice these actions.

The repentant tax collector Zacchaeus not only welcomes Jesus into his house but joyfully promises to give half of his possessions to the poor, and to rebate overpayments four times over if he defrauded anyone (Luke 19:8).

Thus, Jesus cites the words of the prophet Isaiah (Isaiah 61:1–2)[32] in proclaiming his mission: The Spirit of the Lord is upon Me, because He has anointed Me to preach the Gospel to the poor, to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovery of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord.The Gospel of Luke expresses particular concern for the poor as the subjects of Jesus' compassion and ministry.

[39] In the Parable of the Wedding Feast, it is "the poor, the crippled, the blind and the lame" who become God's honored guests, while others reject the invitation because of their earthly cares and possessions (Luke 14:7–14).

A concept related to the accumulation of wealth is Worldliness, which is denounced by the Epistles of James and John: "Don't you know that friendship with the world is enmity with God?

[44] Perrotta characterizes Christianity as not disdaining material wealth as did classical thinkers such as Socrates, the Cynics and Seneca and yet not desiring it as the Old Testament writers did.

"[45] American theologian Robert Grant noted that, while almost all of the Church Fathers condemn the "love of money for its own sake and insist upon the positive duty of almsgiving", none of them seems to have advocated the general application of Jesus' counsel to the rich young man viz.

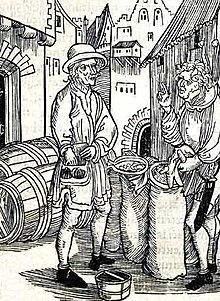

[48] Madeleine Gray describes the medieval system of social welfare as one that was "organized through the Church and underpinned by ideas on the spiritual value of poverty.

As early as the 6th and 7th centuries, the issue of property and move of wealth in the event of outside aggression had been addressed in monastic communities via agreements such as the Consensoria Monachorum.

In reaction to this wealth and power, a reform movement arose which sought a simpler, more austere monastic life in which monks worked with their hands rather than acting as landlords over serfs.

[54] The visible public commitment of the Franciscans to poverty provided to the laity a sharp contrast to the wealth and power of the Church, provoking "awkward questions".

The rising capitalistic middle class resented the drain of their wealth to the Church; in northern Europe, they supported local reformers against the corruption, rapacity and venality which they viewed as originating in Rome.

Joseph Conforti describes the Puritan attitude toward work as taking on "the character of a vocation – a calling through which one improved the world, redeemed time, glorified God, and followed life's pilgrimage toward salvation.

"[60] Gayraud Wilmore characterizes the Puritan social ethic as focused on the "acquisition and proper stewardship of wealth as outward symbols of God's favor and the consequent salvation of the individual.

"[61] Puritans were urged to be producers rather than consumers and to invest their profits to create more jobs for industrious workers who would thus be enabled to "contribute to a productive society and a vital, expansive church."

Puritans were counseled to seek sufficient comfort and economic self-sufficiency but to avoid the pursuit of luxuries or the accumulation of material wealth for its own sake.

[60] In two journal articles published in 1904–05, German sociologist Max Weber propounded a thesis that Reformed (i.e., Calvinist) Protestantism had engendered the character traits and values that under-girded modern capitalism.

Scholars have sought to explain the fact that economic growth has been much more rapid in Northern and Western Europe and its overseas offshoots than in other parts of the world including those where the Catholic and Orthodox Churches have been dominant over Protestantism.

Charging interest is indeed sinful when doing so takes advantage of a person in need as well as when it means investing in corporations involved in the harming of God's creatures.

[67][68] The term and modern concept of "social justice" was coined by the Jesuit Luigi Taparelli in 1840 based on the teachings of St. Thomas Aquinas and given further exposure in 1848 by Antonio Rosmini-Serbati.

Social justice as a secular concept, distinct from religious teachings, emerged mainly in the late twentieth century, influenced primarily by philosopher John Rawls.

[78] In his book, "Moral Philosophy", Jacques Maritain echoed Toynbee's perspective, characterizing the teachings of Karl Marx as a "Christian heresy".

Although King criticized the Soviet Marxist–Leninist Communist regime sharply, he nonetheless commented that Marx's devotion to a classless society made him almost Christian.

The Rerum novarum encyclical of Leo XIII (1891) was the starting point of a Catholic doctrine on social questions that has been expanded and updated over the course of the 20th century.

[88] The influence of liberation theology within the Catholic Church diminished after proponents using Marxist concepts were admonished by the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) in 1984 and 1986.