Chuck Close

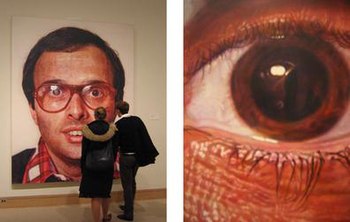

This is an accepted version of this page Charles Thomas Close (July 5, 1940 – August 19, 2021) was an American painter, visual artist, and photographer who made massive-scale photorealist and abstract portraits of himself and others.

[2] As a child, Close had a neuromuscular condition that made it difficult to lift his feet and a bout with nephritis that kept him out of school for most of sixth grade.

[4] Author Graham Thompson writes "One demonstration of the way photography became assimilated into the art world is the success of photorealist painting in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

[8] Local writer John Patric was an early anti-establishment intellectual influence on him, and a role model for the iconoclastic and theatric artist's persona Close learned to project in subsequent years.

[10] Throughout his career, Close expanded his contribution to portraiture through the mastery of such varied drawing and painting techniques as ink, graphite, pastel, watercolor, conté crayon, finger painting, and stamp-pad ink on paper; printmaking techniques, such as mezzotint, etching, woodcuts, linocuts, and silkscreens; as well as handmade paper collage, Polaroid photographs, daguerreotypes, and Jacquard tapestries.

[17] As he explained in a 2009 interview with Cleveland, Ohio's The Plain Dealer newspaper, he made a choice in 1967 to make art hard for himself and force a personal artistic breakthrough by abandoning the paintbrush.

Typically, each square within the grid is filled with roughly executed regions of color (usually consisting of painted rings on a contrasting background) which give the cell a perceived 'average' hue which makes sense from a distance.

The Big Self Portrait is so finely done that even a full page reproduction in an art book is still indistinguishable from a regular photograph.

That day he was at a ceremony honoring local artists in New York City and was waiting to be called to the podium to present an award.

Close delivered his speech and then made his way across the street to Beth Israel Medical Center where he had a seizure which left him paralyzed from the neck down.

Close spoke candidly about the effect disability had on his life and work in the book Chronicles of Courage: Very Special Artists written by Jean Kennedy Smith and George Plimpton and published by Random House.

Viewed from afar, these squares appear as a single, unified image which attempt photo-reality, albeit in pixelated form.

Small bits of irregular paper or inked fingerprints were used as media to achieve astoundingly realistic and interesting results.

Close made a practice, during his final years, of portraying artists who are similarly invested in portraiture, like Cecily Brown, Kiki Smith, Cindy Sherman, and Zhang Huan.

[8] He made his first serious foray into print making in 1972, when he moved himself and family to San Francisco to work on a mezzotint at Crown Point Press for a three-month residency.

[16] From that time on, Close also continued to explore difficult photographic processes such as daguerreotype in collaboration with Jerry Spagnoli and sophisticated modular/cell-based forms such as tapestry.

One was the late Joe Wilfer, who was called the 'prince of pulp' ... and now I'm working with Don Farnsworth in Oakland at...Magnolia Editions: I do the watercolor prints with him, I do the tapestries with him.

"[31] Since 2012, Magnolia Editions has published an ongoing series of archival watercolor prints by Close which use the artist's grid format and the precision afforded by contemporary digital printers to layer water-based pigment on Hahnemuhle rag paper[32] such that the native behavior of watercolor is manifested in each print: "The edges of each pixel bleed with cyan, magenta, and yellow, creating a kind of three-dimensional fog effect behind the intended color swatches.

"[33] The watercolor prints are created using more than 10,000 of Close's hand-painted marks which were scanned into a computer and then digitally rearranged and layered by the artist using his signature grid.

[32] In reviewing this exhibition, Marion Weiss wrote, "Close's Jacquard tapestries are not obviously fragmented, but are created by repeating multicolor warp and weft threads that are optically blended.

)[48] Close credited the Walker Art Center and its then-director Martin Friedman for launching his career with the purchase of Big Self-Portrait (1967–1968)[49] in 1969, the first painting he sold.

[11] After Close abruptly canceled a major show of his work scheduled for 1997 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[51] the Museum of Modern Art announced that it would present a major midcareer retrospective of the artist's work in 1998 (curated by Kirk Varnedoe and later traveling to the Hayward Gallery, London, and other galleries in 1999).

[52][53] In 2003 the Blaffer Gallery at the University of Houston presented a survey of his prints, which travelled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the following year.

[11] His most recent retrospective – "Chuck Close Paintings: 1968/2006", at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid in 2007 – travelled to the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst in Aachen, Germany, and the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia.

[56] In 2016, Close's work was the subject of a retrospective at the Schack Art Center in Everett, Washington, where he attended high school and community college.

Infinite», held at the Gary Tatintsian Gallery in Moscow, featured the artist's works in various techniques including oil painting, mosaic, and tapestry.

Close's work is in the collections of most of the great international museums of contemporary art, including the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the Tate Modern in London, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis who published Chuck Close: Self-Portraits 1967–2005 coauthored with curators Siri Engberg and Madeleine Grynsztejn.

Close previously sold work at auction to raise funds for the campaigns of Hillary Clinton and Al Gore.

[76] In 1998, PBS broadcast documentary filmmaker Marion Cajori's Emmy-nominated short, "Chuck Close: A Portrait in Progress.

In response to the accusations, Close issued a statement to The New York Times, saying, "If I embarrassed anyone or made them feel uncomfortable, I am truly sorry, I didn't mean to.