Chunking (psychology)

In cognitive psychology, chunking is a process by which small individual pieces of a set of information are bound together to create a meaningful whole later on in memory.

These chunks can be highly subjective because they rely on an individual's perceptions and past experiences, which are linked to the information set.

The phenomenon of chunking as a memory mechanism is easily observed in the way individuals group numbers, and information, in day-to-day life.

Similarly, another illustration of the limited capacity of working memory as suggested by George Miller can be seen from the following example: While recalling a mobile phone number such as 9849523450, we might break this into 98 495 234 50.

[8] As stated above, the grouping of the responses occurs as individuals place them into categories according to their inter-relatedness based on semantic and perceptual properties.

Lindley (1966) showed that since the groups produced have meaning to the participant, this strategy makes it easier for an individual to recall and maintain information in memory during studies and testing.

[10] Such systems existed before Miller's paper, but there was no convenient term to describe the general strategy and no substantive and reliable research.

[15] The word chunking comes from a famous 1956 paper by George A. Miller, "The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information".

He imagined this process is useful in scenarios such as "a man just beginning to learn radio-telegraphic code hears each dit and dah as a separate chunk.

Miller wrote: It is a little dramatic to watch a person get 40 binary digits in a row and then repeat them back without error.

One well-known chunking study was conducted by Chase and Ericsson, who worked with an undergraduate student, SF, for over two years.

A later description of the research in The Brain-Targeted Teaching Model for 21st Century Schools states that SF later expanded his strategy by incorporating ages and years, but his chunks were always familiar, which allowed him to recall them more easily.

[19] Another example could be seen with expert musicians in being able to chunk and recall encoded material that best meets the demands they are presented with at any given moment during the performance.

[21] Chase and Simon (1973a) discovered that the skill levels of chess players are attributed to long-term memory storage and the ability to copy and recollect thousands of chunks.

Since it is an excellent tool for enhancing memory, a chess player who utilizes chunking has a higher chance of success.

According to Chase and Simon, while re-examining (1973b), an expert chess master is able to access information in long-term memory storage quickly due to the ability to recall chunks.

Chunks stored in long-term memory are related to the decision of the movement of board pieces due to obvious patterns.

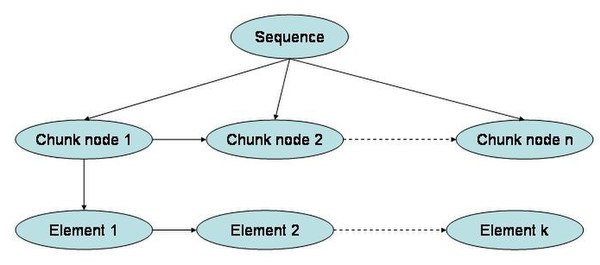

[23] Karl Lashley, in his classic paper on serial order, argued that the sequential responses that appear to be organized in a linear and flat fashion concealed an underlying hierarchical structure.

[26] It is also suggested that during the sequence performance stage (after learning), participants download list items as chunks during pauses.

Output chunks reflect the organization of over-learned motor programs that are generated on-line in working memory.

[28] Chunking is used in adults in different ways which can include low-level perceptual features, category membership, semantic relatedness, and statistical co-occurrences between items.

PARSER is a chunking model designed to account for human behavior by implementing psychologically plausible processes of attention, memory, and associative learning.

A study conducted in 2014, Infants use temporal regularities to chunk objects in memory,[33] allowed for new information and knowledge.

This research showed that 14-month-old infants, like adults, can chunk using their knowledge of object categories: they remembered four total objects when an array contained two tokens of two different types (e.g., two cats and two cars), but not when the array contained four tokens of the same type (e.g., four different cats).

[33] It demonstrates that newborns may employ spatial closeness to tie representations of particular items into chunks, benefiting memory performance as a result.

[36] Chase and Simon in 1973 and later Gobet, Retschitzki, and de Voogt in 2004 showed that chunking could explain several phenomena linked to expertise in chess.

Several successful computational models of learning and expertise have been developed using this idea, such as EPAM (Elementary Perceiver and Memorizer) and CHREST (Chunk Hierarchy and Retrieval Structures).

Franco and Destrebecqz (2012) further studied chunking in language acquisition and found that the presentation of a temporal cue was associated with a reliable prediction of the chunking model regarding learning, but the absence of the cue was associated with increased sensitivity to the strength of transitional probabilities.

Working memory is impaired in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease which affects the ability to do everyday tasks.

The results showed that chunking does improve symbolic sequence performance through decreasing cognitive load and real-time strategy.