Maroons

Maroon bands would venture out throughout the island, usually in large groups, attack villages they encountered, burn down plantations, kill and ransack the Spaniards, and liberate the slaves.

[17] As early as 1655, escaped Africans had formed communities in inland Jamaica, and by the 18th century, Nanny Town and other Jamaican maroon villages began to fight for independent recognition.

Maroon communities faced great odds against their surviving the attacks by hostile colonists,[19] obtaining food for subsistence living,[20] as well as reproducing and increasing their numbers.

[21] One of the most influential maroons was François Mackandal, a houngan or voodoo priest, who led a six-year rebellion against the white plantation owners in Haiti that preceded the Haitian Revolution.

In the plantation colony of Suriname, which England ceded to the Netherlands in the Treaty of Breda (1667), escaped slaves revolted and started to build their villages from the end of the 17th century.

Tours of the village are offered to foreigners and a large festival is put on every January 6 to commemorate the signing of the peace treaty with the British after the First Maroon War.

Disguised pathways, false trails, booby traps, underwater paths, quagmires and quicksand, and natural features were all used to conceal maroon villages.

On 18 June 1695, a gang of maroons of Indonesian and Chinese origins, including Aaron d'Amboine, Antoni (Bamboes) and Paul de Batavia, as well as female escapees Anna du Bengale and Espérance, set fire to the Dutch settlers' Fort Frederick Hendryk (Vieux Grand Port) in an attempt to take over control of the island.

Soon after his arrival in 1735, Mahé de La Bourdonnais assembled and equipped French militia groups made of both civilians and soldiers to fight against the maroons.

[13]: 47–48 [40]: 51 There are 28 identified archaeological sites in the Viñales Valley related to runaway African slaves or maroons of the early 19th century; the material evidence of their presence is found in caves of the region, where groups settled for various lengths of time.

Oral tradition tells that maroons took refuge on the slopes of the mogotes and in the caves; the Viñales Municipal Museum has archaeological exhibits that depict the life of runaway slaves, as deduced through archeological research.

[43] In Dominica, escaped slaves joined indigenous Kalinago in the island's densely forested interior to create maroon communities, which were constantly in conflict with the British colonial authorities throughout the period of formal chattel slavery.

A statue called the Le Nègre Marron or the Nèg Mawon is an iconic bronze bust that was erected in the heart of Port-au-Prince to commemorate the role of maroons in Haitian independence.

[55] People who escaped from slavery during the Spanish occupation of the island of Jamaica fled to the interior and joined the Taíno living there, forming refugee communities.

Certain maroon factions became so formidable that they made treaties with local colonial authorities,[57] sometimes negotiating their independence in exchange for helping to hunt down other slaves who escaped.

Due to their difficulties and those of Black Loyalists settled at Nova Scotia and England after the American Revolution, Great Britain established a colony in West Africa, Sierra Leone.

The DNA analysis of contemporary persons from this area shows maternal ancestry from the Mandinka, Wolof, and Fulani peoples through the mtDNA African haplotype associated with them yet also carried at low frequencies by Spaniards, L1b, which is present here.

Some were found in the interior of modern-day Honduras, along the trade routes by which silver mined on the Pacific side of the isthmus was carried by slaves down to coastal towns such as Trujillo or Puerto Caballos to be shipped to Europe.

The Miskito Sambu were a maroon group who formed from slaves who revolted on a Portuguese ship around 1640, wrecking the vessel on the coast of Honduras-Nicaragua and escaping into the interior.

Viceroy Canete felt unable to subdue these maroons, so he offered them terms that entailed a recognition of their freedom, provided they refused to admit any newcomers and returned runaways to their owners.

[66][65]: 94–97 The Costa Chica of Guerrero and of Oaxaca include many hard-to-access areas that also provided refuge for slaves escaping Spanish ranches and estates on the Pacific coast.

Many were formerly part of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, but have been excluded since the late 20th century by new membership rules that require proving Native American descent from historic documents.

Robeson County, North Carolina was a place where Blacks, Native Americans, and even some outlaw whites lived together and intermingled producing a people of great genetic mixture.

Part of the reason for the massive size of Palmares was due to its location in Brazil — at the median point between the Atlantic Ocean and Guinea, an important area of the African slave trade.

Quilombo dos Palmares was a self-sustaining community of escaped slaves from the Portuguese settlements in Brazil, "a region perhaps the size of Portugal in the hinterland of Bahia".

Eventually, the Spanish agreed to peace terms with the palenque of San Basilio, and in 1772, this community of maroons was included within the Mahates district, as long they no longer accepted any further runaways.

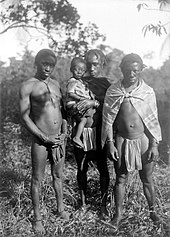

[91] In the Guianas, escaped slaves, locally known as 'Bushinengues', fled to the interior and joined with indigenous peoples and created several independent tribes, among them the Saramaka, the Paramaka, the Ndyuka (Aukan), the Kwinti, the Aluku (Boni), and the Matawai.

[99] Between 1986 and 1992,[100] the Surinamese Interior War was waged by the Jungle Commando, a guerrilla group fighting for the rights of the maroon minority, against the military dictatorship of Dési Bouterse.

[101] In 2005, following a ruling by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the Suriname government agreed to compensate survivors of the 1986 Moiwana village massacre, in which soldiers had slaughtered 39 unarmed Ndyuka people, mainly women and children.

[107]: 64–65 One of Guillermo's deputies, Ubaldo the Englishman, whose christened name was Jose Eduardo de la Luz Perera, was initially born a slave in London, sold to a ship captain, and took a number of trips before eventually being granted his freedom.