Cirque

Alternative names for this landform are corrie (from Scottish Gaelic: coire, meaning a pot or cauldron)[1] and cwm (Welsh for 'valley'; pronounced [kʊm]).

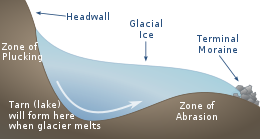

The floor of the cirque ends up bowl-shaped, as it is the complex convergence zone of combining ice flows from multiple directions and their accompanying rock burdens.

Hence, it experiences somewhat greater erosion forces and is most often overdeepened below the level of the cirque's low-side outlet (stage) and its down-slope (backstage) valley.

[2] The fluvial cirque or makhtesh, found in karst landscapes, is formed by intermittent river flow cutting through layers of limestone and chalk leaving sheer cliffs.

A common feature for all fluvial-erosion cirques is a terrain which includes erosion resistant upper structures overlying materials which are more easily eroded.

Water that flows into the bergschrund can be cooled to freezing temperatures by the surrounding ice, allowing freeze-thaw free mechanisms to occur.

As glaciers can only originate above the snowline, studying the location of present-day cirques provides information on past glaciation patterns and on climate change.

Yet another type of fluvial erosion-formed cirque is found on Réunion island, which includes the tallest volcanic structure in the Indian Ocean.

[9] A common feature for all fluvial-erosion cirques is a terrain which includes erosion resistant upper structures overlying materials which are more easily eroded.