Reforms of Russian orthography

As the language evolved, several letters, notably the yuses (Ѫ, Ѭ, Ѧ, Ѩ) were gradually and unsystematically discarded from both secular and church usage over the next centuries.

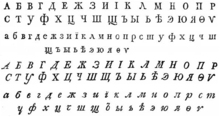

[1] The printed Russian alphabet began to assume its modern shape when Peter I introduced his "civil script" (гражданский шрифт) type reform in 1708.

With the strength of the historic tradition diminishing, Russian spelling in the 18th century became rather inconsistent, both in practice and in theory, as Mikhail Lomonosov advocated a morphophonemic orthography and Vasily Trediakovsky a phonemic one.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, miscellaneous adjustments were made ad hoc, as the Russian literary language came to assume its modern and highly standardized form.

The ѳ remained more common, though it became quite rare as a "Western" (French-like) pronunciation had been adopted for many words; for example, ѳеатръ (ḟeatr, [fʲɪˈatr], 'theater') became театръ (teatr, [tʲɪˈatr]).

Attempts to reduce spelling inconsistency culminated in the 1885 standard textbook of Yakov Karlovich Grot, which retained its authority through 21 editions until the Russian Revolution of 1917.

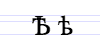

[4] Russian orthography was made simpler and easier by unifying several adjectival and pronominal inflections, conflating the letter ѣ (Yat) with е, ѳ with ф, and і and ѵ with и. Additionally, the archaic mute yer became obsolete, including the ъ (the "hard sign") in final position following consonants (thus eliminating practically the last graphical remnant of the Old Slavonic open-syllable system).

Because of this, the usage of the apostrophe as a dividing sign became widespread in place of ъ (e.g., под’ём, ад’ютант instead of подъём, адъютант), and came to be perceived as a part of the reform (even if, from the point of view of the letter of the decree of the Council of People's Commissars, such uses were mistakes).

The reform resulted in some economy in writing and typesetting, due to the exclusion of Ъ at the end of words—by the reckoning of Lev Uspensky, text in the new orthography was shorter by one-thirtieth.

Replacement of онѣ, однѣ, ея by они, одни, её was especially controversial, as these feminine pronouns were deeply rooted in the language and extensively used by writers and poets.

Прошло сто лѣтъ, и юный градъ, Полнощныхъ странъ краса и диво, Изъ тьмы лѣсовъ, изъ топи блатъ Вознесся пышно, горделиво; Гдѣ прежде финскій рыболовъ, Печальный пасынокъ природы, Одинъ у низкихъ береговъ Бросалъ въ невѣдомыя воды Свой ветхой неводъ, нынѣ тамъ По оживленнымъ берегамъ Громады стройныя тѣснятся Дворцовъ и башенъ; корабли Толпой со всѣхъ концовъ земли Къ богатымъ пристанямъ стремятся; Въ гранитъ одѣлася Нева; Мосты повисли надъ водами; Темно-зелеными садами Ея покрылись острова, И передъ младшею столицей Померкла старая Москва, Какъ передъ новою царицей Порфироносная вдова.

Люблю тебя, Петра творенье, Люблю твой строгій, стройный видъ, Невы державное теченье, Береговой ея гранитъ, Твоихъ оградъ узоръ чугунный, Твоихъ задумчивыхъ ночей Прозрачный сумракъ, блескъ безлунный, Когда я въ комнатѣ моей Пишу, читаю безъ лампады, И ясны спящія громады Пустынныхъ улицъ, и свѣтла Адмиралтейская игла[...]

Прошло сто лет, и юный град, Полнощных стран краса и диво, Из тьмы лесов, из топи блат Вознесся пышно, горделиво; Где прежде финский рыболов, Печальный пасынок природы, Один у низких берегов Бросал в неведомые воды Свой ветхой невод, ныне там По оживленным берегам Громады стройные теснятся Дворцов и башен; корабли Толпой со всех концов земли К богатым пристаням стремятся; В гранит оделася Нева; Мосты повисли над водами; Темно-зелеными садами Ее покрылись острова, И перед младшею столицей Померкла старая Москва, Как перед новою царицей Порфироносная вдова.

Люблю тебя, Петра творенье, Люблю твой строгий, стройный вид, Невы державное теченье, Береговой ее гранит, Твоих оград узор чугунный, Твоих задумчивых ночей Прозрачный сумрак, блеск безлунный, Когда я в комнате моей Пишу, читаю без лампады, И ясны спящие громады Пустынных улиц, и светла Адмиралтейская игла[...]

By 1952, normatives on checking school works, the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, and the reference book for typographers by K. I. Bylinsky had declared the letter Ё to be optional.

[20] Following the renewed discussion in papers and journals, a new Orthographic Commission began work in 1962, under the Russian Language Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

That instruction for non-native speakers of Russian was one of the central concerns of further reform is indicated in the resistance to Efimov's proposal to drop the terminal "ь" (soft sign) from feminine nouns, as it helps learners identify gender category.