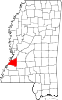

Claiborne County, Mississippi

As in other parts of the Delta, the bottomlands areas further from the river remained largely frontier and undeveloped until after the American Civil War.

Grand Gulf, a port on the Mississippi River, shipped thousands of bales of cotton annually before the Civil War.

[7] Businesses in the county seat of Port Gibson, which served the area, included a cotton gin and a cottonseed oil mill (which continued into the 20th century.)

More than 80 percent of African-American workers were involved in sharecropping from the late 19th century into the 1930s, shaping all aspects of daily life for them.

[13] Excluded from the political process and suffering lynchings and other violence, many blacks left the county and state in the Great Migration.

Most of these rural blacks migrated to the industrial North and Midwest cities, such as Chicago, to seek jobs and other opportunities elsewhere.

[14] Despite the passage of national civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s, African Americans in Claiborne County continued to struggle against white supremacy in most aspects of their lives.

"African Americans insisted on dignified treatment and full inclusion in the community's public life, while whites clung to paternalistic notions of black inferiority and defended inherited privilege.

"[15] In reaction to harassment and violence, in 1966 blacks formed a group, Deacons for Defense, which armed to protect the people and was strictly for self-defense.

After shadowing police to prevent abuses, its leaders eventually began to work closely with the county sheriff to keep relations peaceful.

In the November election, Evers led an African-American vote for the Independent senatorial candidate, Prentiss Walker, who won in those counties but lost to incumbent James O. Eastland, a white Democrat.

Walker was a conservative who in 1964 was elected as the first Republican Congressman from Mississippi in the 20th century, as part of a major realignment of political parties in the South.

To gain integration of public facilities and more opportunities in local businesses, where no black clerks were hired, African Americans undertook an economic boycott of merchants in the county seat of Port Gibson.

While criticized for some of his methods, Evers gained support from the national NAACP for his apparent effectiveness, from the segregationist Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission for negotiating on certain elements, and from local African Americans and white liberals.

[4] The boycott was upheld as a legal form of political protest by the United States Supreme Court.

In November 1966 Floyd Collins ran for the school board; he was the county's first black candidate for electoral office since Reconstruction.

[21] Since 2003, when Mississippi had to redistrict because it lost a seat in Congress, Claiborne County has been included in the black-majority 2nd congressional district.