Clairaut's theorem (gravity)

Clairaut's theorem characterizes the surface gravity on a viscous rotating ellipsoid in hydrostatic equilibrium under the action of its gravitational field and centrifugal force.

It was published in 1743 by Alexis Claude Clairaut in a treatise[1] which synthesized physical and geodetic evidence that the Earth is an oblate rotational ellipsoid.

Although it had been known since antiquity that the Earth was spherical, by the 17th century evidence was accumulating that it was not a perfect sphere.

In 1672 Jean Richer found the first evidence that gravity was not constant over the Earth (as it would be if the Earth were a sphere); he took a pendulum clock to Cayenne, French Guiana and found that it lost 2+1⁄2 minutes per day compared to its rate at Paris.

British physicist Isaac Newton explained this in his Principia Mathematica (1687) in which he outlined his theory and calculations on the shape of the Earth.

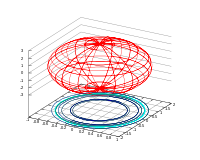

[6] Newton theorized correctly that the Earth was not precisely a sphere but had an oblate ellipsoidal shape, slightly flattened at the poles due to the centrifugal force of its rotation.

Using geometric calculations, he gave a concrete argument as to the hypothetical ellipsoid shape of the Earth.

[7] The goal of Principia was not to provide exact answers for natural phenomena, but to theorize potential solutions to these unresolved factors in science.

Two prominent researchers that he inspired were Alexis Clairaut and Pierre Louis Maupertuis.

In order to do so, they went on an expedition to Lapland in an attempt to accurately measure a meridian arc.

From such measurements they could calculate the eccentricity of the Earth, its degree of departure from a perfect sphere.

Clairaut confirmed that Newton's theory that the Earth was ellipsoidal was correct, but that his calculations were in error, and he wrote a letter to the Royal Society of London with his findings.

[9] In it Clairaut pointed out (Section XVIII) that Newton's Proposition XX of Book 3 does not apply to the real earth.

Newton had in fact said that this was on the assumption that the matter inside the earth was of a uniform density (in Proposition XIX).

However, he also thought this would mean the equator was further from the centre than what his theory predicted, and Clairaut points out that the opposite is true.

Clairaut's theorem says that the acceleration due to gravity g (including the effect of centrifugal force) on the surface of a spheroid in hydrostatic equilibrium (being a fluid or having been a fluid in the past, or having a surface near sea level) at latitude φ is:[10][11]

This formula holds when the surface is perpendicular to the direction of gravity (including centrifugal force), even if (as usually) the density is not constant (in which case the gravitational attraction can be calculated at any point from the shape alone, without reference to

[12] Clairaut derived the formula under the assumption that the body was composed of concentric coaxial spheroidal layers of constant density.

[13] This work was subsequently pursued by Laplace, who assumed surfaces of equal density which were nearly spherical.

[12][14] The English mathematician George Stokes showed in 1849[12] that the theorem applied to any law of density so long as the external surface is a spheroid of equilibrium.

For a detailed account of the construction of the reference Earth model of geodesy, see Chatfield.