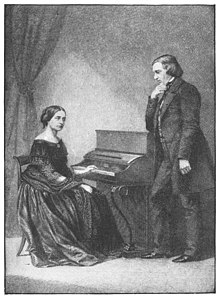

Clara Schumann

Regarded as one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era, she exerted her influence over the course of a 61-year concert career, changing the format and repertoire of the piano recital by lessening the importance of purely virtuosic works.

After Robert Schumann's early death, she continued her concert tours in Europe for decades, frequently with the violinist Joseph Joachim and other chamber musicians.

[6] In Weimar, she performed a bravura piece by Henri Herz for Goethe, who presented her with a medal with his portrait and a written note saying: "For the gifted artist Clara Wieck".

"[12] Chopin described her playing to Franz Liszt, who came to hear one of Wieck's concerts and subsequently praised her extravagantly in a letter that was published in the Parisian Revue et Gazette Musicale and later, in translation, in the Leipzig journal Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.

[13] On 15 March, she was named a Königliche und Kaiserliche Österreichische Kammer-virtuosin ("Royal and Imperial Austrian Chamber Virtuoso"),[14] Austria's highest musical honor.

The judge allowed the marriage, which took place in Schönefeld church on 13 September 1840, the day before Clara's 21st birthday, when she attained majority status.

[19] In February 1854, Robert Schumann had a mental collapse, attempted suicide, and was admitted, at his request, to a sanatorium in the village of Endenich near Bonn, where he stayed for the last two years of his life.

In March 1854, Brahms, Joachim, Albert Dietrich, and Julius Otto Grimm spent time with Clara Schumann, playing music for her and with her to divert her mind from the tragedy.

She wrote that he played "with a finish, a depth of poetic feeling, his whole soul in every note, so ideally, that I have never heard violin-playing like it, and I can truly say that I have never received so indelible an impression from any virtuoso."

A lasting friendship developed between Clara and Joseph, which for more than forty years never failed her in things great or small, never wavered in its loyalty.

She was invited to play in a London Philharmonic Society[a] concert by conductor William Sterndale Bennett, a good friend of Robert's.

In May 1856, she played Robert Schumann's Piano Concerto in A minor with the New Philharmonic Society[b] conducted by Dr Wylde, who as she said had "led a dreadful rehearsal" and "could not grasp the rhythm of the last movement".

[40] Schumann also spent many years in London participating in the Popular Concerts with Joachim and the celebrated Italian cellist Carlo Alfredo Piatti.

Two sisters, Louisa and Susanna Pyne, singers and managers of an opera company in England, and a man named Saunders, made all the arrangements.

She was accompanied by her oldest daughter Marie, who wrote from Manchester to her friend Rosalie Leser that in Edinburgh the pianist "was received with tempestuous applause and had to give an encore, so had Joachim.

[30][34] In 1883, she performed Beethoven's Choral Fantasy with the newly-formed Berlin Philharmonic, and was enthusiastically celebrated, although she was playing with an injured hand in great pain, having fallen on a staircase the previous day.

Part of her responsibility included earning money by giving concerts, though she continued to play throughout her life, not just for the income but because she was an artist by training and nature.

Her eldest living son Ludwig suffered from mental illness like his father and, in her words, eventually had to be "buried alive" in an institution.

Another daughter, Eugenie, who had been too young when her father died to remember him, wrote a book, Erinnerungen (Memoirs), published in 1925, covering her parents and Brahms.

On the evening of 3 May, Robert and Clara heard that the revolution against King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony for not accepting the "constitution for a German Confederation" had arrived in Dresden.

When she was 14 and her future husband 23, he wrote to her: Tomorrow precisely at eleven o'clock I will play the adagio from Chopin's Variations and at the same time I shall think of you very intently, exclusively of you.

Now my request is that you should do the same, so that we may see and meet each other in spirit.In her early years, her repertoire, selected by her father, was showy and in the style common to the time, with works by Friedrich Kalkbrenner, Adolf von Henselt, Sigismond Thalberg, Henri Herz, Johann Peter Pixis, Carl Czerny and her own compositions.

[65] As part of the broad musical education given to her by her father, Clara Wieck learned to compose, and from childhood to middle age she produced a good body of work.

Clara wrote that "composing gives me great pleasure... there is nothing that surpasses the joy of creation, if only because through it one wins hours of self-forgetfulness, when one lives in a world of sound".

[51][77] She also edited 20 sonatas by Domenico Scarlatti, letters (Jugendbriefe) by her husband in 1885, and his piano works with fingering and other instructions (Fingersatz und Vortragsbezeichnungen) in 1886.

When he performed, Liszt flailed his arms, tossed his head, and pursed his lips,[90] inspiring a Lisztomania across Europe which has been compared to the Beatlemania of female fans of The Beatles over a century later.

[95] The New Weimar Club, a formal society with Liszt at its center, held an anniversary celebration of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, the magazine Robert Schumann had founded, in his birthplace Zwickau, and conspicuously neglected to invite members of the opposing party, including his widow, Clara.

Trained by her father to play by ear and memorize, she gave public performances from memory as early as age thirteen, a fact noted as exceptional by her reviewers.

In her early career, before her marriage, she played the customary bravura pieces designed to showcase the artist's technique, often in the form of arrangements or variations on popular themes from operas, written by virtuosos such as Thalberg, Herz, or Henselt.

[109] Twin Spirits, a live theatrical performance involving a chamber ensemble of actors, singers, and musicians, also delves into Clara Schumann's life story.