Classical Latin

Since spoken Latinitas has become extinct (in favor of subsequent registers), the rules of politus (polished) texts may give the appearance of an artificial language.

No texts by Classical Latin authors are noted for the type of rigidity evidenced by stylized art, with the exception of repetitious abbreviations and stock phrases found on inscriptions.

[2] The word is a transliteration of Greek κλῆσις (clēsis, or "calling") used to rank army draftees by property from first to fifth class.

It was under this construct that Marcus Cornelius Fronto (an African-Roman lawyer and language teacher) used scriptores classici ("first-class" or "reliable authors") in the second century AD.

[3] This is the first known reference (possibly innovated during this time) to Classical Latin applied by authors, evidenced in the authentic language of their works.

Thomas Sébillet's Art Poétique (1548), "les bons et classiques poètes françois", refers to Jean de Meun and Alain Chartier, who the first modern application of the words.

[citation needed] According to Merriam Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, the term classical (from classicus) entered modern English in 1599, some 50 years after its re-introduction to the continent.

[6] In 1736, Robert Ainsworth's Thesaurus Linguae Latinae Compendarius turned English words and expressions into "proper and classical Latin.

Teuffel's classification, still in use today (with modifications), groups classical Latin authors into periods defined by political events rather than by style.

Like Teuffel, Cruttwell encountered issues while attempting to condense the voluminous details of time periods in an effort to capture the meaning of phases found in their various writing styles.

It is best, however, not to narrow unnecessarily the sphere of classicity; to exclude Terence on the one hand or Tacitus and Pliny on the other, would savour of artificial restriction rather than that of a natural classification."

[11][12] Wagner's translation of Teuffel's writing is as follows: The golden age of the Roman literature is that period in which the climax was reached in the perfection of form, and in most respects also in the methodical treatment of the subject-matters.

This is what is called the Augustan Age, which was perhaps of all others the most brilliant, a period at which it should seem as if the greatest men, and the immortal authors, had met together upon the earth, in order to write the Latin language in its utmost purity and perfection...[13] and of Tacitus, his conceits and sententious style is not that of the golden age...[14]Evidently, Teuffel received ideas about golden and silver Latin from an existing tradition and embedded them in a new system, transforming them as he thought best.

In Cruttwell's introduction, the Golden Age is dated 80 BC – AD 14 (from Cicero to Ovid), which corresponds to Teuffel's findings.

With the exception of a few major writers, such as Cicero, Caesar, Virgil and Catullus, ancient accounts of Republican literature praise jurists and orators whose writings, and analyses of various styles of language cannot be verified because there are no surviving records.

The reputations of Aquilius Gallus, Quintus Hortensius Hortalus, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, and many others who gained notoriety without readable works, are presumed by their association within the Golden Age.

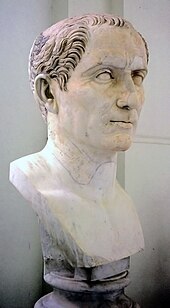

A list of canonical authors of the period whose works survived in whole or in part is shown here: The Golden Age is divided by the assassination of Julius Caesar.

Cicero and his contemporaries were replaced by a new generation who spent their formative years under the old constructs, and forced to make their mark under the watchful eye of a new emperor.

Though he introduces das silberne Zeitalter der römischen Literatur, (The Silver Age of Roman Literature)[16] from the death of Augustus to the death of Trajan (14–117 AD), he also mentions parts of a work by Seneca the Elder, a wenig Einfluss der silbernen Latinität (a slight influence of silver Latin).

He may have been influenced in that regard by one of his sources E. Opitz, who in 1852 had published specimen lexilogiae argenteae latinitatis, which includes Silver Latinity.

Of the Silver Age proper, Teuffel points out that anything like freedom of speech had vanished with Tiberius:[18] ...the continual apprehension in which men lived caused a restless versatility...

Hence it was dressed up with abundant tinsel of epigrams, rhetorical figures and poetical terms... Mannerism supplanted style, and bombastic pathos took the place of quiet power.The content of new literary works was continually proscribed by the emperor, who exiled or executed existing authors and played the role of literary man, himself (typically badly).

Hence arose a declamatory tone, which strove by frigid and almost hysterical exaggeration to make up for the healthy stimulus afforded by daily contact with affairs.

With the decay of freedom, taste sank...In Cruttwell's view (which had not been expressed by Teuffel), Silver Latin was a "rank, weed-grown garden," a "decline.

Once again, Cruttwell evidences some unease with his stock pronouncements: "The Natural History of Pliny shows how much remained to be done in fields of great interest."

The philosophic prose of a good emperor was in no way compatible with either Teuffel's view of unnatural language, or Cruttwell's depiction of a decline.

Apparently, in the worst implication of their views, there was no such thing as Classical Latin by the ancient definition, and some of the very best writing of any period in world history was deemed stilted, degenerate, unnatural language.

By valuing Classical Latin as "first class", it was better to write with Latinitas selected by authors who were attuned to literary and upper-class languages of the city as a standardized style.