Classical central-force problem

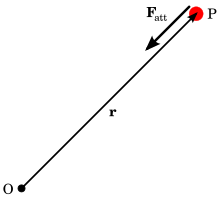

In classical mechanics, the central-force problem is to determine the motion of a particle in a single central potential field.

In other words, a central force must act along the line joining O with the present position of the particle.

According to Newton's second law of motion, the central force F generates a parallel acceleration a scaled by the mass m of the particle[note 2]

To show this, it suffices that the work W done by the force depends only on initial and final positions, not on the path taken between them.

because the partial derivatives are zero for a central force; the magnitude F does not depend on the angular spherical coordinates θ and φ.

In this respect, the central-force problem is analogous to the Schwarzschild geodesics in general relativity and to the quantum mechanical treatments of particles in potentials of spherical symmetry.

In reality, however, the Sun also moves (albeit only slightly) in response to the force applied by the planet Mercury.

The motion of a particle under a central force F always remains in the plane defined by its initial position and velocity.

Consequently, the particle's position r (and hence velocity v) always lies in a plane perpendicular to L.[9] Since the motion is planar and the force radial, it is customary to switch to polar coordinates.

[9] In these coordinates, the position vector r is represented in terms of the radial distance r and the azimuthal angle φ.

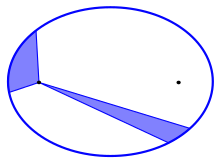

[11] The magnitude of h also equals twice the areal velocity, which is the rate at which area is being swept out by the particle relative to the center.

[12] Thus, the areal velocity is constant for a particle acted upon by any type of central force; this is Kepler's second law.

Making the change of variables to the inverse radius u = 1/r[17] yields where C is a constant of integration and the function G(u) is defined by

Take the scalar product of Newton's second law of motion with the particle's velocity where the force is obtained from the potential energy

[24] If there are two turning points such that the radius r is bounded between rmin and rmax, then the motion is contained within an annulus of those radii.

[23] As the radius varies from the one turning point to the other, the change in azimuthal angle φ equals[23]

[25] In general, if the angular momentum L is nonzero, the L2/2mr2 term prevents the particle from falling into the origin, unless the effective potential energy goes to negative infinity in the limit of r going to zero.

In classical physics, many important forces follow an inverse-square law, such as gravity or electrostatics.

For an attractive force (α < 0), the orbit is an ellipse, a hyperbola or parabola, depending on whether u1 is positive, negative, or zero, respectively; this corresponds to an eccentricity e less than one, greater than one, or equal to one.

[27] Similarly, only six possible linear combinations of power laws give solutions in terms of circular and elliptic functions[28][29]

was mentioned by Newton, in corollary 1 to proposition VII of the principia, as the force implied by circular orbits passing through the point of attraction.

Newton showed that, with adjustments in the initial conditions, the addition of such a force does not affect the radial motion of the particle, but multiplies its angular motion by a constant factor k. An extension of Newton's theorem was discovered in 2000 by Mahomed and Vawda.

Newton used an equivalent of leapfrog integration to convert the continuous motion to a discrete one, so that geometrical methods may be applied.

The difference vector Δr = rBC − rAB equals ΔvΔt (green line), where Δv = vBC − vAB is the change in velocity resulting from the force at point B.

The areas of the triangles OAB and OBK are equal, because they share the same base (rAB) and height (r⊥).

Conversely, if the areas of all such triangles are equal, then Δr must be parallel to rB, from which it follows that F is a central force.

Since the azimuthal angle φ does not appear in the Hamiltonian, its conjugate momentum pφ is a constant of the motion.

[31] Adopting the radial distance r and the azimuthal angle φ as the coordinates, the Hamilton-Jacobi equation for a central-force problem can be written

where S = Sφ(φ) + Sr(r) − Etott is Hamilton's principal function, and Etot and t represent the total energy and time, respectively.

where pφ is a constant of the motion equal to the magnitude of the angular momentum L. Thus, Sφ(φ) = Lφ and the Hamilton–Jacobi equation becomes