Schwarzschild geodesics

In general relativity, Schwarzschild geodesics describe the motion of test particles in the gravitational field of a central fixed mass

For example, they provide accurate predictions of the anomalous precession of the planets in the Solar System and of the deflection of light by gravity.

Schwarzschild geodesics pertain only to the motion of particles of masses so small they contribute little to the gravitational field.

In 1931, Yusuke Hagihara published a paper showing that the trajectory of a test particle in the Schwarzschild metric can be expressed in terms of elliptic functions.

[1] Samuil Kaplan in 1949 has shown that there is a minimum radius for the circular orbit to be stable in Schwarzschild metric.

A white dwarf star is much denser, but even here the ratio at its surface is roughly 250 parts in a million.

In the case of the planet Mercury this simplification introduces an error more than twice as large as the relativistic effect.

Substituting these constants into the definition of the Schwarzschild metric yields an equation of motion for the radius as a function of the proper time

) with zero angular momentum (Although the proper time is trivial in the photonic case, one can define an affine parameter

Other tachyonic solutions can enter a black hole and re-exit into the parallel exterior region.

The fundamental equation of the orbit is easier to solve[note 1] if it is expressed in terms of the inverse radius

of this elliptic function is given by the formula To recover the Newtonian solution for the planetary orbits, one takes the limit as the Schwarzschild radius

becomes the trigonometric sine function Consistent with Newton's solutions for planetary motions, this formula describes a focal conic of eccentricity

The function sn and its square sn2 have periods of 4K and 2K, respectively, where K is defined by the equation[note 2] Therefore, the change in φ over one oscillation of

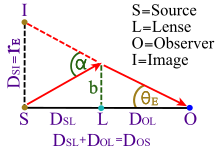

Although this formula is approximate, it is accurate for most measurements of gravitational lensing, due to the smallness of the ratio

As shown below and elsewhere, this inverse-cubic energy causes elliptical orbits to precess gradually by an angle δφ per revolution where

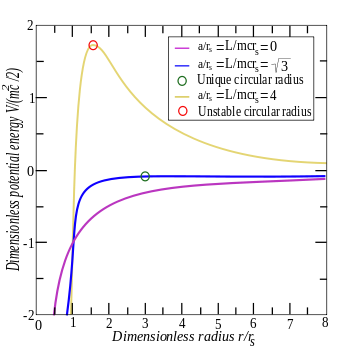

values, giving a critical inner radius rinner at which a particle is drawn inexorably inwards to

There are two radii at which this balancing can occur, denoted here as rinner and router which are obtained using the quadratic formula.

At the outer radius, however, the circular orbits are stable; the third term is less important and the system behaves more like the non-relativistic Kepler problem.

In our notation, the classical orbital angular speed equals At the other extreme, when a2 approaches 3rs2 from above, the two radii converge to a single value The quadratic solutions above ensure that router is always greater than 3rs, whereas rinner lies between 3⁄2 rs and 3rs.

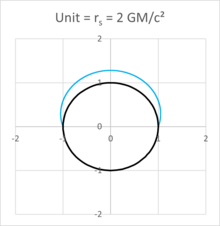

For massless particles, a goes to infinity, implying that there is a circular orbit for photons at rinner = 3⁄2 rs.

The orbital precession rate may be derived using this radial effective potential V. A small radial deviation from a circular orbit of radius router will oscillate stably with an angular frequency which equals Taking the square root of both sides and performing a Taylor series expansion yields Multiplying by the period T of one revolution gives the precession of the orbit per revolution where we have used ωφT = 2п and the definition of the length-scale a.

Substituting the definition of the Schwarzschild radius rs gives This may be simplified using the elliptical orbit's semiaxis A and eccentricity e related by the formula to give the precession angle The non-vanishing Christoffel symbols for the Schwarzschild-metric are:[9] According to Einstein's theory of general relativity, particles of negligible mass travel along geodesics in the space-time.

For lightlike (or null) orbits (which are traveled by massless particles such as the photon), the proper time is zero and, strictly speaking, cannot be used as the variable

[13] Geodesics in space-time are defined as curves for which small local variations in their coordinates (while holding their endpoints events fixed) make no significant change in their overall length s. This may be expressed mathematically using the calculus of variations where τ is the proper time, s = cτ is the arc-length in space-time and T is defined as in analogy with kinetic energy.

If the derivative with respect to proper time is represented by a dot for brevity T may be written as Constant factors (such as c or the square root of two) don't affect the answer to the variational problem; therefore, taking the variation inside the integral yields Hamilton's principle The solution of the variational problem is given by Lagrange's equations When applied to t and φ, these equations reveal two constants of motion which may be expressed in terms of two constant length-scales,

[15] The advantage of this approach is that it equates the motion of the particle with the propagation of a wave, and leads neatly into the derivation of the deflection of light by gravity in general relativity, through Fermat's principle.

Using the Schwarzschild metric gμν, this equation becomes where we again orient the spherical coordinate system with the plane of the orbit.

The time t and azimuthal angle φ are cyclic coordinates, so that the solution for Hamilton's principal function S can be written where

(energy) can be combined to form one equation that is true even for photons and other massless particles for which the proper time along a geodesic is zero.