Classification of manifolds

These categories are related by forgetful functors: for instance, a differentiable manifold is also a topological manifold, and a differentiable map is also continuous, so there is a functor

Thus given two categories, the two natural questions are: In more general categories, this structure set has more structure: in Diff it is simply a set, but in Top it is a group, and functorially so.

There are two usual ways to give a classification: explicitly, by an enumeration, or implicitly, in terms of invariants.

tori, and an invariant that classifies them is the genus or Euler characteristic.

Manifolds have a rich set of invariants, including: Modern algebraic topology (beyond cobordism theory), such as Extraordinary (co)homology, is little-used in the classification of manifolds, because these invariants are homotopy-invariant, and hence don't help with the finer classifications above homotopy type.

Being homogeneous (away from any boundary), manifolds have no local point-set invariants, other than their dimension and boundary versus interior, and the most used global point-set properties are compactness and connectedness.

Characteristic classes and characteristic numbers are the corresponding generalized homological invariants, but they do not classify manifolds in higher dimension (they are not a complete set of invariants): for instance, orientable 3-manifolds are parallelizable (Steenrod's theorem in low-dimensional topology), so all characteristic classes vanish.

In higher dimensions, characteristic classes do not in general vanish, and provide useful but not complete data.

) presented as CW complexes or handlebodies, there is no algorithm for determining if they are isomorphic (homeomorphic, diffeomorphic).

Thus one cannot even compute the fundamental group of a given high-dimensional manifold, much less a classification.

This ineffectiveness is a fundamental reason why surgery theory does not classify manifolds up to homeomorphism.

Conversely, negative curvature is generic: for instance, any manifold of dimension

This phenomenon is evident already for surfaces: there is a single orientable (and a single non-orientable) closed surface with positive curvature (the sphere and projective plane), and likewise for zero curvature (the torus and the Klein bottle), and all surfaces of higher genus admit negative curvature metrics only.

Thus dimension 4 differentiable manifolds are the most complicated: they are neither geometrizable (as in lower dimension), nor are they classified by surgery (as in higher dimension or topologically), and they exhibit unusual phenomena, most strikingly the uncountably infinitely many exotic differentiable structures on R4.

Notably, differentiable 4-manifolds is the only remaining open case of the generalized Poincaré conjecture.

", meaning "If surgery worked in low dimensions, what would low-dimensional manifolds look like?"

A connected compact 1-dimensional manifold without boundary is homeomorphic (or diffeomorphic if it is smooth) to the circle.

A second countable, non-compact 1-dimensional manifold is homeomorphic or diffeomorphic to the real line.

For example: Every connected closed 2-dimensional manifold (surface) admits a constant curvature metric, by the uniformization theorem.

This is a classical result, and as stated, easy (the full uniformization theorem is subtler).

Every closed 3-dimensional manifold can be cut into pieces that are geometrizable, by the geometrization conjecture, and there are 8 such geometries.

The proof (the Solution of the Poincaré conjecture) is analytic, not topological.

Four-dimensional manifolds are the most unusual: they are not geometrizable (as in lower dimensions), and surgery works topologically, but not differentiably.

Similarly, differentiable 4-manifolds is the only remaining open case of the generalized Poincaré conjecture.

Analogously to the classification of manifolds, in high codimension (meaning more than 2), embeddings are classified by surgery, while in low codimension or in relative dimension, they are rigid and geometric, and in the middle (codimension 2), one has a difficult exotic theory (knot theory).

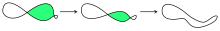

Particularly topologically interesting classes of maps include embeddings, immersions, and submersions.

Fundamental results in embeddings and immersions include: Key tools in studying these maps are: One may classify maps up to various equivalences: Diffeomorphisms up to cobordism have been classified by Matthias Kreck[4]