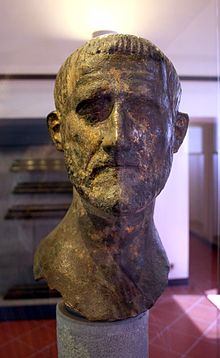

Claudius Gothicus

The most significant source for Claudius II (and the only one regarding his early life) is the collection of imperial biographies called the Historia Augusta.

In 4th century, Claudius was declared a relative of Constantine the Great's father, Constantius Chlorus, and, consequently, of the ruling dynasty.

[8] The Historia Augusta refers to him as a member of the gens Flavia, likely an attempt to further connect him with the future emperor Flavius Valerius Constantius.

[9] Before coming to power, Claudius served with the Roman army, where he had a successful career and secured appointments to the highest military posts.

Historian François Pashau suggests that this passage was invented in order to contrast the successful pagan commander Claudius with the unlucky Christian generals who allowed the ruin of Greece by the Gothic leader Alaric I in 396.

[11] In addition, Trebellius Pollio reveals that Decius rewarded Claudius after he demonstrated his strength while fighting another soldier at the Games of Mars.

Gallienus was seriously weakened by his failure to defeat Postumus in the West, and his acceptance of Odaenathus ruling a de facto independent kingdom within the Roman Empire in the East.

By 268, this situation had changed, as Odaenathus was assassinated, most likely due to court intrigue, and Gallienus fell victim to a mutiny in his own ranks.

When victory appeared to be near, Gallienus made the mistake of approaching the city walls too closely and was gravely injured, compelling him to cease his campaign against Postumus.

The Scythians successfully invaded the Balkans in the early months of 268, and Aureolus, a commander of the Roman cavalry based in Milan, declared himself an ally of Postumus and went so far as to claim the imperial throne for himself.

Despite this, scholars assume Gallienus's efforts were focused on Aureolus, the officer who betrayed him, and the defeat of the Herulians was left to his successor, Claudius Gothicus.

In a different and more controversial account, Aureolus forges a document in which Gallienus appears to be plotting against his generals and makes sure it falls into the hands of the emperor's senior staff.

[20] Whichever story is true, Gallienus was killed in the summer of 268, probably between July and October,[21][22][5] and Claudius was chosen by the army outside of Milan to succeed him.

Accounts tell of people hearing the news of the new emperor, and reacting by murdering Gallienus's family members until Claudius declared he would respect the memory of his predecessor.

"[2] He then turned on the Gallic Empire, ruled by a pretender for the past eight years and encompassing Britain, Gaul, and the Iberian Peninsula.

Heraclianus, Appollinaris, Placidianus, or Marcianus may not have been of Danubian origin themselves, but none of them were members of the Severan aristocracy, and all of them appear to owe their prominence to their military roles.

Marcus Aurelius Probus (another emperor in waiting) was also of Balkan background, and from a family enfranchised in the time of Caracalla.

Claudius assumed the consulship in 269 with Paternus, a member of the prominent senatorial family, the Paterni, who had supplied consuls and urban prefects throughout Gallienus's reign, and thus were quite influential.

A colleague of Antiochianus, Virius Orfitus, also the descendant of a powerful family, would continue to hold influence during his father's term as prefect.

An obscure passage in the Historia Augusta's life of Gallienus states that he had sent an army under Aurelius Heraclianus to the region that had been annihilated by Zenobia.

At this time, the prefect of Egypt was Tenagino Probus, described as an able soldier who not only defeated an invasion of Cyrenaica by the nomadic tribes to the south in 269, but also was successful in hunting down Scythian ships in the Mediterranean.

However, he did not see the same success in Egypt, for a group allied to the Palmyrene empire, led by Timagenes, undermined Probus, defeated his army, and killed him in a battle near the modern city of Cairo in the late summer of 270.

[29] Generally, when a Roman commander is killed it is taken as a sign that a state of war is in existence, and if we can associate the death of Heraclianus in 270, as well as an inscription from Bostra recording the rebuilding of a temple destroyed by the Palmyrene army, then these violent acts could be interpreted the same way.

As David Potter writes, "The coins of Vaballathus avoid claims to imperial power: he remains vir consularis, rex, imperator, dux Romanorum, a range of titles that did not mimic those of the central government.

It is possible that the thin line between office and the status that accompanied it were dismissed in the Palmyrene court, especially when the circumstance worked against the interests of a regime that was able to defeat Persia, which a number of Roman emperors had failed to do.

[34] Before his death, he is thought to have named Aurelian as his successor, though Claudius's brother Quintillus briefly seized power.

[42] A short history of imperial Rome, entitled De Caesaribus, written by Aurelius Victor in 361, states that Claudius consulted the Sibylline Books prior to his campaigns against the Goths.

[47] The legend was retold in later texts, and in the Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493, involved the Roman priest being martyred during a general persecution of Christians.

The text states that St. Valentine was beaten with clubs and finally beheaded for giving aid to Christians in Rome.

[47] The Golden Legend of 1260 recounts how St. Valentine refused to deny Christ before the "Emperor Claudius" in 270 and as a result was beheaded.