Effects of climate change on human health

[3] Factors such as age, gender and socioeconomic status influence to what extent these effects become wide-spread risks to human health.

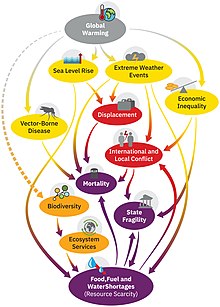

[9]: 1867 Extreme weather, including increased storms, floods, droughts, heat waves and wildfires can directly cause injury, illness, or death.

[10] These include worsening water quality, air pollution, reduced food availability, and faster spread of disease-carrying insects.

[11] Both direct and indirect health effects and their impact vary across the world and between different groups of people according to age, gender, mobility and other factors.

[14] Extreme weather events, such as floods, hurricanes, heatwaves, droughts and wildfires can result in injuries, death and the spread of infectious diseases.

[citation needed] For example, local epidemics can occur due to loss of infrastructure, such as hospitals and sanitation services, but also because of climate changes creating a more suitable weather for disease-carrying organisms.

[16] Unless greenhouse gas emissions are reduced, regions inhabited by a third of the human population could become as hot as the hottest parts of the Sahara within 50 years.

[28]: 1498 As of 2020, only two weather stations had recorded 35 °C wet-bulb temperatures, and only very briefly, but the frequency and duration of these events is expected to rise with ongoing climate change.

[29][30][31] Global warming above 1.5 degrees risks making parts of the tropics uninhabitable because the threshold for the wet bulb temperature may be passed.

[33][35] The risk of dying from chronic lung disease during a heat wave has been estimated at 1.8–8.2% higher compared to average summer temperatures.

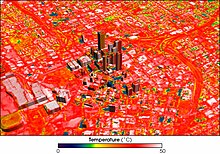

For example, they often have extensive areas of asphalt, reduced greenery along with many large heat-retaining buildings that physically block cooling breezes and ventilation.

[37] Cities are often on the front-line of climate change due to their densely concentrated populations, the urban heat island effect, their frequent proximity to coasts and waterways, and reliance on ageing physical infrastructure networks.

[39] Health experts warn that "exposure to extreme heat increases the risk of death from cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory conditions and all-cause mortality.

[3]: 17 Mortality due to heat waves could be reduced if buildings were better designed to modify the internal climate, or if the occupants were better educated about the issues, so they can take action on time.

It found that during 2021, high temperature reduced global potential labour hours by 470 billion – a 37% increase compared to the average annual loss that occurred during the 1990s.

[57] The health effects of wildfire smoke exposure include exacerbation and development of respiratory illness such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder; increased risk of lung cancer, mesothelioma and tuberculosis; increased airway hyper-responsiveness; changes in levels of inflammatory mediators and coagulation factors; and respiratory tract infection.

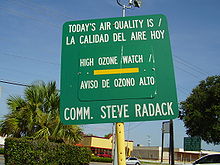

Climate change projections show that rising temperatures and water vapour in the atmosphere will likely increase surface ozone in polluted areas like the eastern United States.

[84][85] Exposure to ozone (and the pollutants that produce it) is linked to premature death, asthma, bronchitis, heart attack, and other cardiopulmonary problems.

[81] People who are most at risk from breathing in ozone air pollution are those with respiratory issues, children, older adults and those who typically spend long periods of time outside such as construction workers.

Food insecurity is increasing at the global level (some of the underlying causes are related to climate change, others are not) and about 720–811 million people suffered from hunger in 2020.

Some kinds of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) create neurotoxins, hepatoxins, cytotoxins or endotoxins that can cause serious and sometimes fatal neurological, liver and digestive diseases in humans.

These include those of cleaner air, healthier diets (e.g. less red meat), more active lifestyles, and increased exposure to green urban spaces.

These benefits were attributable to the mitigation of direct greenhouse gas emissions and the accompanying actions that reduce exposure to harmful pollutants, as well as improved diets and safe physical activity.

[121][122] Climate change mitigation policies can lead to lower emissions of co-emitted air pollutants, for instance by shifting away from fossil fuel combustion.

[123] Implementation of the climate pledges made in the run-up to the Paris Agreement could therefore have significant benefits for human health by improving air quality.

[124] The replacement of coal-based energy with renewables can lower the number of premature deaths caused by air pollution and decrease health costs associated with coal-related respiratory diseases.

The study assessed deaths from heat exposure in elderly people, increases in diarrhea, malaria, dengue, coastal flooding, and childhood undernutrition.

The greatest impact tends to fall on the most vulnerable such as the poor, women, children, the elderly, people with pre-existing health concerns, other minorities and outdoor workers.

[47]: 1008, 1128 Studies have found that when communicating climate change with the public, it can help encourage engagement if it is framed as a health concern, rather than as an environmental issue.

[131][144] By the early years of the 21st century, climate change was increasingly addressed as a public health concern at a global level, for example in 2006 at Nairobi by UN secretary general Kofi Annan.