Climate inertia

Increasing fossil-fuel carbon emissions are a primary inertial driver of change to Earth's climate during recent decades, and have risen along with the collective socioeconomic inertia of its 8 billion human inhabitants.

[6] Earth's inertial responses are important because they provide the planet's diversity of life and its human civilization further time to adapt to an acceptable degree of planetary change.

[9][10] An aim of Integrated assessment modelling, summarized for example as Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP), is to explore Earth system risks that accompany large inertia and uncertainty in the trajectory of human drivers of change.

[13]: 19–72 Studies of climate sensitivity and inertia are concerned with quantifying the most basic manner in which a sustained forcing perturbation will cause the system to deviate within or initially away from its relatively stable state of the present Holocene epoch.

Inertial time constants indicate a base rate for forced changes, but lengthy values provide no guarantee of long-term system evolution along a smooth pathway.

[18][19] Such events might precipitate a nonlinear rearrangement of internal energy flows along with more rapid shifts in climate and/or other systems at regional to global scale.

[13]: 10–15, 73–76 The response of global surface temperature (GST) to a step-like doubling of the atmospheric CO2 concentration, and its resultant forcing, is defined as the Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity (ECS).

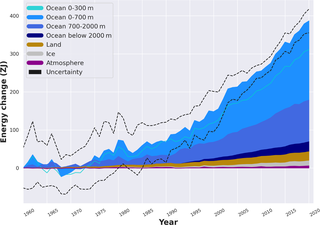

The global ocean is Earth's largest thermal reservoir that functions to regulate the planet's climate; acting as both a sink and a source of energy.

The slower transportation of heat into the extreme deep ocean, subsurface land sediments, and thick ice sheets will continue until the new Earth system equilibrium has been reached.

For instance, coral bleaching can occur in a single warm season, while trees may be able to persist for decades under a changing climate, but be unable to regenerate.