Coral bleaching

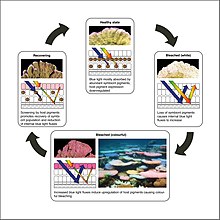

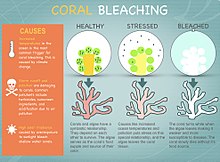

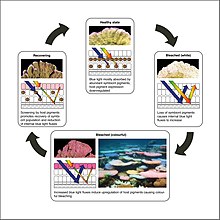

Negative environmental conditions, such as abnormally warm or cool temperatures, high light, and even some microbial diseases, can lead to the breakdown of the coral/zooxanthellae symbiosis.

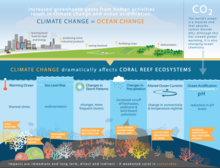

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report in 2022 found that: "Since the early 1980s, the frequency and severity of mass coral bleaching events have increased sharply worldwide".

[50]: 416 Coral reefs, as well as other shelf-sea ecosystems, such as rocky shores, kelp forests, seagrasses, and mangroves, have recently undergone mass mortalities from marine heatwaves.

"[55] In a study conducted on the Hawaiian mushroom coral Lobactis scutaria, researchers discovered that higher temperatures and elevated levels of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) had a detrimental impact on its reproductive physiology.

The economic implications are profound, as coral reefs contribute approximately $2.7 trillion annually to the global economy, including $36 billion from tourism alone.

Although a forthcoming shift to a La Niña phase may offer some relief, regions such as Florida have already experienced complete die-offs in some reefs, where temperatures have risen to 101°F (38.3°C).

[79] A model from one study by Speers et al. calculated direct losses to fisheries from decreased coral cover to be around $49–69 billion, if human societies continue to emit high levels of greenhouse gases.

[79] These economic losses also have important political implications, as they fall disproportionately on developing countries where the reefs are located, namely in Southeast Asia and around the Indian Ocean.

[79][81][82] It would cost more for countries in these areas to respond to coral reef loss as they would need to turn to different sources of income and food, in addition to losing other ecosystem services such as ecotourism.

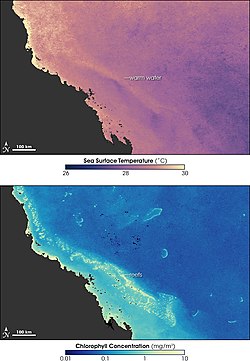

[23] The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) monitors for bleaching "hot spots", areas where sea surface temperature rises 1 °C or more above the long-term monthly average.

[89] The first mass global bleaching events were recorded in 1998 and 2010, which was when the El Niño caused the ocean temperatures to rise and worsened the corals living conditions.

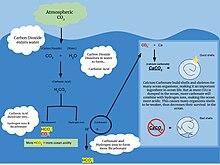

[94] A recent study from the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future found that with the combination of acidification and temperature rises, the levels of CO2 could become too high for coral to survive in as little as 50 years.

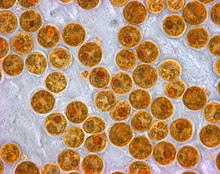

The host organism harnesses the products of photosynthesis, i.e. oxygen, sugar, etc., and in exchange, the zooxanthellae are offered housing and protection, as well as carbon dioxide, phosphates, and other essential inorganic compounds that help them to survive and thrive.

[28] Infectious bacteria of the species Vibrio shiloi are the bleaching agent of Oculina patagonica in the Mediterranean Sea, causing this effect by attacking the zooxanthellae.

[101][103] V. shiloi then penetrates the coral's epidermis, multiplies, and produces both heat-stable and heat-sensitive toxins, which affect zooxanthellae by inhibiting photosynthesis and causing lysis.

In late November 2016, surveys of 62 reefs showed that long term heat stress from climate change caused a 29% loss of shallow water coral.

[132][133][134] Moreover, the Maldivian coral reef faces risks from the growing tourism industry and coastal construction,[135] as well as land reclamation projects,[136] alongside natural challenges such as diseases.

[150] In 2010, researchers at Penn State discovered corals that were thriving while using an unusual species of symbiotic algae in the warm waters of the Andaman Sea in the Indian Ocean.

[152][153] In 2010, researchers from Stanford University also found corals around the Samoan Islands that experience a drastic temperature increase for about four hours a day during low tide.

[162] In 2020, scientists reported to have evolved 10 clonal strains of a common coral microalgal endosymbionts at elevated temperatures for 4 years, increasing their thermal tolerance for climate resilience.

[26] Discovering what causes reefs to be resilient or recover from bleaching events is of primary importance because it helps inform conservation efforts and protect coral more effectively.

As Emma Camp, a National Geographic Explorer, marine bio-geochemist and an ambassador for Biodiversity for the charity IBEX Earth,[171] suggests, the super-corals could have the capability to help with the damaged reefs long-term.

[citation needed] While it can take 10 to 15 years to restore damaged and bleached coral reefs,[172] the super-corals could have lasting impacts despite climate change as the oceans rise in temperature and gain more acidity.

Bolstered by the research of Ruth Gates, Camp has looked into lower oxygen levels and the extreme, unexpected habitats that reefs can be found in across the globe.

[176] Lowered numbers of grazing species after coral bleaching in the Caribbean has been likened to sea-urchin-dominated systems which do not undergo regime shifts to fleshy macroalgae dominated conditions.

[61] Van Oppen is also working on developing a type of algae that will have a symbiotic relationship with corals and can withstand water temperature fluctuations for long periods of time.

MPAs defend ecosystems from overfishing, which allows multiple species of fish to thrive and deplete seaweed density, making it easier for young coral organisms to grow and increase in population/strength.

[182] There are a number of stressors locally impacting coral bleaching, including sedimentation, continual support of urban development, land change, increased tourism, untreated sewage, and pollution.

[46] If the populations of the fish and corals in the reef are high, then we can use the area as a place to gather food and things with medicinal properties, creating jobs for people who can collect these specimens.

[188] The Paris Agreement has offered reasons for hope by pledging nations worldwide to maintain the rise in global average temperatures significantly below 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels, with concerted endeavors aimed at capping the increase at 1.5°C.