Clonal selection

In immunology, clonal selection theory explains the functions of cells of the immune system (lymphocytes) in response to specific antigens invading the body.

The concept was introduced by Australian doctor Frank Macfarlane Burnet in 1957, in an attempt to explain the great diversity of antibodies formed during initiation of the immune response.

[1][2] The theory has become the widely accepted model for how the human immune system responds to infection and how certain types of B and T lymphocytes are selected for destruction of specific antigens.

In 1955, Danish immunologist Niels Jerne put forward a hypothesis that there is already a vast array of soluble antibodies in the serum prior to any infection.

According to Burnet's hypothesis, among antibodies are molecules that can probably correspond with varying degrees of precision to all, or virtually all, the antigenic determinants that occur in biological material other than those characteristic of the body itself.

Each type of pattern is a specific product of a clone of lymphocytes and it is the essence of the hypothesis that each cell automatically has available on its surface representative reactive sites equivalent to those of the globulin they produce.

[5][9] In 1958, Gustav Nossal and Joshua Lederberg showed that one B cell always produces only one antibody, which was the first direct evidence supporting the clonal selection theory.

In 1974, Niels Kaj Jerne proposed that the immune system functions as a network that is regulated via interactions between the variable parts of lymphocytes and their secreted molecules.

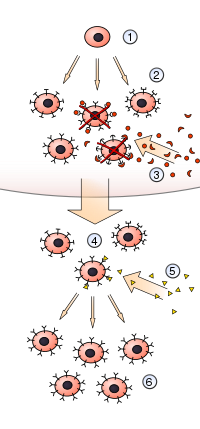

1) A hematopoietic stem cell undergoes differentiation and genetic rearrangement to produce

2) immature lymphocytes with many different antigen receptors. Those that bind to

3) antigens from the body's own tissues are destroyed, while the rest mature into

4) inactive lymphocytes. Most of these never encounter a matching

5) foreign antigen, but those that do are activated and produce

6) many clones of themselves.