V(D)J recombination

The process ultimately results in novel amino acid sequences in the antigen-binding regions of immunoglobulins and TCRs that allow for the recognition of antigens from nearly all pathogens including bacteria, viruses, parasites, and worms as well as "altered self cells" as seen in cancer.

In 1987, Susumu Tonegawa was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for his discovery of the genetic principle for generation of antibody diversity".

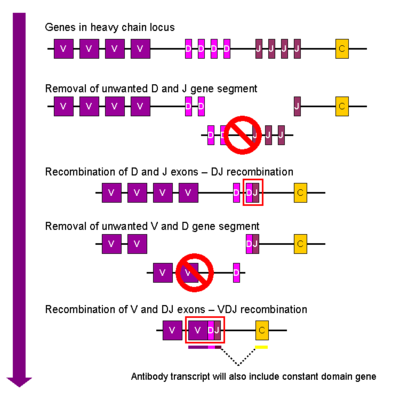

[3] DNA rearrangement causes one copy of each type of gene segment to go in any given lymphocyte, generating an enormous antibody repertoire; roughly 3×1011 combinations are possible, although some are removed due to self reactivity.

The T cell receptor in this sense is the topological equivalent to an antigen-binding fragment of the antibody, both being part of the immunoglobulin superfamily.

During thymocyte development, the T cell receptor (TCR) chains undergo essentially the same sequence of ordered recombination events as that described for immunoglobulins.

mRNA transcription splices out any intervening sequence and allows translation of the full length protein for the TCR β-chain.

The key enzymes involved are recombination activating genes 1 and 2 (RAG), terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), and Artemis nuclease, a member of the ubiquitous non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway for DNA repair.

[4] Several other enzymes are known to be involved in the process and include DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 4 (XRCC4), DNA ligase IV, non-homologous end-joining factor 1 (NHEJ1; also known as Cernunnos or XRCC4-like factor [XLF]), the recently discovered Paralog of XRCC4 and XLF (PAXX), and DNA polymerases λ and μ.

[5] Some enzymes involved are specific to lymphocytes (e.g., RAG, TdT), while others are found in other cell types and even ubiquitously (e.g., NHEJ components).

[10] The current model is that DNA nicking and hairpin formation occurs on both strands simultaneously (or nearly so) in a complex known as a recombination center.

While originally thought to be lost during successive cell divisions, there is evidence that signal joints may re-enter the genome and lead to pathologies by activating oncogenes or interrupting tumor suppressor gene function(s)[Ref].

The coding ends are processed further prior to their ligation by several events that ultimately lead to junctional diversity.

[18] The process of hairpin opening by Artemis is a crucial step of V(D)J recombination and is defective in the severe combined immunodeficiency (scid) mouse model.

DNA polymerases λ and μ then insert additional nucleotides as needed to make the two ends compatible for joining.