Clothing in ancient Rome

Exotic fabrics were available, at a price; silk damasks, translucent gauzes, cloth of gold, and intricate embroideries; and vivid, expensive dyes such as saffron yellow or Tyrian purple.

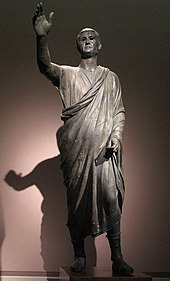

In literature and poetry, Romans were the gens togata ("togate race"), descended from a tough, virile, intrinsically noble peasantry of hard-working, toga-wearing men and women.

From at least the late Republic onward, the upper classes favoured ever longer and larger togas, increasingly unsuited to manual work or physically active leisure.

[3] These early morning, formal "greeting sessions" were an essential part of Roman life, in which clients visited their patrons, competing for favours or investment in business ventures.

Stolae typically comprised two rectangular segments of cloth joined at the side by fibulae and buttons in a manner allowing the garment to be draped in elegant but concealing folds, covering the whole body including the feet.

[20][21] Two ancient literary sources mention use of a coloured strip or edging (a limbus) on a woman's "mantle", or on the hem of their tunic; probably a mark of their high status, and presumably purple.

Elite invective mocked the aspirations of wealthy, upwardly mobile freedmen who boldly flouted this prohibition, donned a toga, or even the trabea of an equites, and inserted themselves as equals among their social superiors at the games and theatres.

Advice to farm-owners by Cato the Elder and Columella on the regular supply of adequate clothing to farm-slaves was probably intended to mollify their otherwise harsh conditions, and maintain their obedience.

Thick-soled wooden clogs, with leather uppers, were available for use in wet weather, and by rustics and field-slaves[39] Archaeology has revealed many more non-standardised footwear patterns and variants in use over the existence of the Roman Empire.

[40] Public protocol required red ankle boots for senators, and shoes with crescent-shaped buckles for equites, though some wore Greek-style sandals to "go with the crowd".

Soldiers on active duty wore short trousers under a military kilt, sometimes with a leather jerkin or felt padding to cushion their armour, and a triangular scarf tucked in at the neck.

Cicero's "sagum-wearing" soldiers versus "toga-wearing" civilians are rhetorical and literary trope, referring to a wished-for transition from military might to peaceful, civil authority.

[50] Roman military clothing was probably less uniform and more adaptive to local conditions and supplies than is suggested by its idealised depictions in contemporary literature, statuary and monuments.

Even when foreign garments – such as full-length trousers – proved more practical than standard issue, soldiers and commanders who used them were viewed with disdain and alarm by their more conservative compatriots, for undermining Rome's military virtus by "going native".

[55] Some of the Vindolanda tablets mention the despatch of clothing – including cloaks, socks, and warm underwear – by families to their relatives, serving at Brittania's northern frontier.

[59] The Vestal Virgins tended Rome's sacred fire, in Vesta's temple, and prepared essential sacrificial materials employed by different cults of the Roman state.

They wore a close-fitting, rounded cap (apex) topped with a spike of olive-wood; and the laena, a long, semi-circular "flame-coloured" cloak fastened at the shoulder with a brooch or fibula.

Each carried a sword, wore a short, red military cloak (paludamentum) and ritually struck a bronze shield, whose ancient original was said to have fallen from heaven.

[63] In 204 BC, the Galli priesthood were brought to Rome from Phrygia, to serve the "Trojan" Mother Goddess Cybele and her consort Attis on behalf of the Roman state.

[66] In part, this reflects the expansion of Rome's empire, and the adoption of provincial fashions perceived as attractively exotic, or simply more practical than traditional forms of dress.

In the later empire after Diocletian's reforms, clothing worn by soldiers and non-military government bureaucrats became highly decorated, with woven or embellished strips, clavi, and circular roundels, orbiculi, added to tunics and cloaks.

Trousers – considered barbarous garments worn by Germans and Persians – achieved only limited popularity in the latter days of the empire, and were regarded by conservatives as a sign of cultural decay.

Britannia was noted for its woolen products, which included a kind of duffel coat (the birrus brittanicus), fine carpets, and felt linings for army helmets.

In the early Empire the Senate passed legislation forbidding the wearing of silk by men because it was viewed as effeminate[75] but there was also a connotation of immorality or immodesty attached to women who wore the material,[76] as illustrated by Seneca the Elder: I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body.

The Historia Augusta claims that the emperor Elagabalus was the first Roman to wear garments of pure silk (holoserica) as opposed to the usual silk/cotton blends (subserica); this is presented as further evidence of his notorious decadence.

[71][77] Moral dimensions aside, Roman importation and expenditure on silk represented a significant, inflationary drain on Rome's gold and silver coinage, to the benefit of foreign traders and loss to the empire.

A rare luxury cloth with a beautiful golden sheen, known as sea silk, was made from the long silky filaments or byssus produced by Pinna nobilis, a large Mediterranean clam.

[96] The expansion of trade networks during the early Imperial era brought the dark blue of Indian indigo to Rome; though desirable and costly in itself, it also served as a base for fake Tyrian purple.

Unprocessed animal hides were supplied directly to tanners by butchers, as a byproduct of meat production; some was turned to rawhide, which made a durable shoe-sole.

Landowners and livestock ranchers, many of whom were of the elite class, drew a proportion of profits at each step of the process that turned their animals into leather or hide and distributed it through empire-wide trade networks.