Clusivity

While imagining that this sort of distinction could be made in other persons (particularly the second) is straightforward, in fact the existence of second-person clusivity (you vs. you and they) in natural languages is controversial and not well attested.

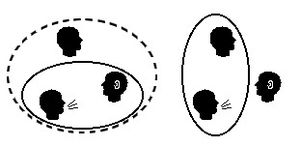

[3] Clusivity paradigms may be summarized as a two-by-two grid: In some languages, the three first-person pronouns appear to be unrelated roots.

That is the case for Chechen, which has singular со (so), exclusive тхо (txo), and inclusive вай (vay).

In others, however, all three are transparently simple compounds, as in Tok Pisin, an English creole spoken in Papua New Guinea, which has singular mi, exclusive mi-pela, and inclusive yu-mi (a compound of mi with yu "you") or yu-mi-pela.

However, in Hadza, the inclusive, ’one-be’e, is the plural of the singular ’ono (’one-) "I", and the exclusive, ’oo-be’e, is a separate [dubious – discuss] root.

No European language outside the Caucasus makes this distinction grammatically, but some constructions[example needed] may be semantically inclusive or exclusive.

Several Polynesian languages, such as Samoan and Tongan, have clusivity with overt dual and plural suffixes in their pronouns.

[2] He concludes that oft-repeated rumors regarding the existence of second-person clusivity—or indeed, any [+3] pronoun feature beyond simple exclusive we[8] – are ill-founded, and based on erroneous analysis of the data.

(Tok Pisin, an English-Melanesian creole, generally has the inclusive–exclusive distinction, but this varies with the speaker's language background.)