Evidence-based policy

[3] The effectiveness of evidence-based policy hinges upon the presence of quality data, proficient analytical skills, and political backing for the utilization of scientific information.

[2] While proponents of evidence-based policy have identified certain types of evidence, such as scientifically rigorous evaluation studies like randomized controlled trials, as optimal for policymakers to consider, others argue that not all policy-relevant areas are best served by quantitative research.

For example, policies concerning human rights, public acceptability, or social justice may necessitate different forms of evidence than what randomized trials provide.

Furthermore, evaluating policy often demands moral philosophical reasoning in addition to the assessment of intervention effects, which randomized trials primarily aim to provide.

[5] This semantic shift allows for continued reflection on the need to elevate the rigor and quality of evidence used, while sidestepping some of the limitations or reductionist notions occasionally associated with the term evidence-based.

[5] Despite these nuances, the phrase "evidence-based policy" is still widely employed, generally signifying a desire for evidence to be used in a rigorous, high-quality, and unbiased manner, while avoiding its misuse for political ends.

Some contend that the earliest instance of EBM dates back to the 11th century when Ben Cao Tu Jing from the Song dynasty suggested a method to evaluate the efficacy of ginseng.

Although elements of an evidence-based approach can be traced back as far as the fourteenth century, it was popularized more recently during the tenure of the Blair Government in the United Kingdom.

The Alliance, operating throughout the UK, promoted the use of high-quality evidence to inform decisions on strategy, policy, and practice through advocacy, research publication, idea sharing, advice, event hosting, and training.

For instance, Michael Kremer and Rachel Glennerster, curious about strategies to enhance students' test scores, conducted randomized controlled trials in Kenya.

They experimented with new textbooks and flip charts, and smaller class sizes, but they discovered that the only intervention that boosted school attendance was treating intestinal worms in children.

In their analysis of vocational education in prisons run by the California Department of Corrections, researchers Andrew J. Dick, William Rich, and Tony Waters found that political factors inevitably influenced "evidence-based decisions," which were ostensibly neutral and technocratic.

Due to the difficulty in quantifying some effects and outcomes of the policy, the focus is primarily on whether benefits will outweigh costs, rather than assigning specific values.

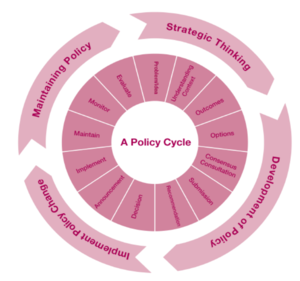

Policy development processes are complex, seldom linear or logical, thus making the direct application of presented information by policy-makers an unlikely scenario.

These factors encompass information gaps, secrecy, the necessity for rapid responses versus slow data availability, political expediency (what is popular), and a lack of interest among policy-makers in making policies more scientifically grounded.

The ODI suggested that, in the face of limited progress in evidence-based policy, individuals and organizations possessing relevant data should leverage the emotional appeal and narrative power typically associated with politics and advertising to influence decision-makers.

Instead of relying solely on tools like cost–benefit analysis and logical frameworks,[28] the ODI recommended identifying key players, crafting compelling narratives, and simplifying complex research data into clear, persuasive stories.

The Future Health Systems consortium, based on research undertaken in six countries across Asia and Africa, has identified several key strategies to enhance the incorporation of evidence into policy-making.

[29] These strategies include enhancing the technical capacity of policy-makers; refining the presentation of research findings; leveraging social networks; and establishing forums to facilitate the connection between evidence and policy outcomes.

Additionally, they argue that the prioritization of RCTs could lead to the criticism of evidence-based policy being overly focused on narrowly defined 'interventions', which implies surgical actions on one causal factor to influence its effect.

[41] Furthermore, there have been reports[42] of frontline public servants, such as hospital managers, making decisions that detrimentally affect patient care to meet predetermined targets.