Code Girls

In the months prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States Military began to recruit women to work for their various branches, as the men who previously occupied these positions were deployed overseas to fight in the war.

[3] After the attack, the Navy's recruitment activities and advertisements increased dramatically as the United States' joined the Allied Forces to fight Axis powers during World War II.

[4] Candidates were invited to secret meetings where they were offered the opportunity to take a code-breaking training course and were sworn to secrecy- exposing their work was considered treason and could have been punishable by death.

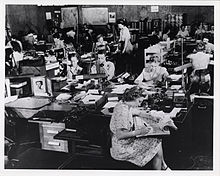

[1] The code girls worked in many branches of the armed services, including: U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, U.S. Coastguard, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Marine Corps, etc.

Prior to D-Day, they shared false information and radio messages to intentionally mislead the Germans about the Allied Forces' landing location.

[8] The result of their work allowed the U.S. naval forces to plan and execute the Battle of Midway, ultimately changing the course of the Pacific Theater of World War II.

These recruited women acquiring adept skills in math, science, and foreign languages, were to remain dutiful and patriotic with no expectation of public credit for their concealed intelligence work.

[5] The Code Girls of World War II laid out important foundations and pioneered the work that would become part of modern-day cybersecurity and communication agencies.

[9] Additionally to the Army’s code breaking operation, there was an African American group unit (implemented by Eleanor Roosevelt) that helped with the enciphered communications of certain companies, and to get better insight of who was collaborating with dictators such as Mitsubishi and Hitler.

Another significant cryptanalyst named Elizabeth Smith Friedman was the first to discover the US government’s codebreaking bureau in 1916, where she worked for Riverbank at an unconventional Illinois estate.

In September 1940, due to Genevieve Grotjan’s key expertise, the Allies were able to get information on the Japanese diplomats’ communications throughout World War II.

Specifically, Ada Comstock urged for the Navy to train the undergraduates in cryptanalysis, realizing how the country lacked a demand of educated women after the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor.

The Japanese fleet code called JN-25 was used by these women who created the cryptoanalytic assembly line, and aided in shooting down Isoroku Yamamoto's plane.

All of the machines that targeted and attacked the German Enigma ciphers were managed by women, additionally they tracked the locations of Allied convoys and U-boats.