SIGABA

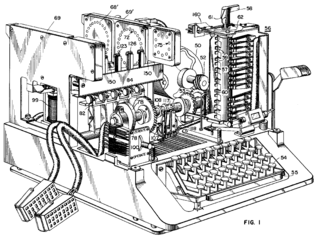

Like many machines of the era it used an electromechanical system of rotors to encipher messages, but with a number of security improvements over previous designs.

In the case of the famous Enigma machine, these attacks were supposed to be upset by moving the rotors to random locations at the start of each new message.

This, however, proved not to be secure enough, and German Enigma messages were frequently broken by cryptanalysis during World War II.

William Friedman, director of the US Army's Signals Intelligence Service, devised a system to correct for this attack by truly randomizing the motion of the rotors.

His modification consisted of a paper tape reader from a teletype machine attached to a small device with metal "feelers" positioned to pass electricity through the holes.

There was little money for encryption development in the US before the war, so Friedman and Rowlett built a series of "add on" devices called the SIGGOO (or M-229) that were used with the existing M-134s in place of the paper tape reader.

These were external boxes containing a three rotor setup in which five of the inputs were live, as if someone had pressed five keys at the same time on an Enigma, and the outputs were "gathered up" into five groups as well — that is all the letters from A to E would be wired together for instance.

He found little interest for it in the Navy until early 1937, when he showed it to Commander Laurance Safford, Friedman's counterpart in the Office of Naval Intelligence.

On the downside, the SIGABA was also large, heavy, expensive, difficult to operate, mechanically complex, and fragile.

It found widespread use in the radio rooms of US Navy ships, but as a result of these practical problems the SIGABA simply couldn't be used in the field.

This said, new speculative evidence emerged more recently that the M-209 code was broken by German cryptanalysts during World War II.

[3] Because SIGABA did not have a reflector, a 26+ pole switch was needed to change the signal paths through the alphabet maze between the encryption and decryption modes.

The reader was expected to understand that a word like “xebra” in a decrypted message was actually “zebra.” The printer automatically added a space between each group of five characters during encryption.

This allowed the most sensitive elements of the machine to be stored in more secure safes and to be quickly thrown overboard or otherwise destroyed if capture was threatened.

Axis prisoners of war (POWs) were also interrogated with the goal of finding evidence that US cryptography had been broken.

A decrypted JN-A-20 message, dated 24 January 1942, sent from the naval attaché in Berlin to vice chief of Japanese Naval General Staff in Tokyo stated that "joint Jap[anese]-German cryptanalytical efforts" to be "highly satisfactory", since the "German[s] have exhibited commendable ingenuity and recently experienced some success on English Navy systems", but are "encountering difficulty in establishing successful techniques of attack on 'enemy' code setup".

In September 1944, when the Allies were advancing steadily on the Western front, the war diary of the German Signal Intelligence Group recorded: "U.S. 5-letter traffic: Work discontinued as unprofitable at this time".

On February 3, 1945, a truck carrying a SIGABA system in three safes was stolen while its guards were visiting a brothel in recently liberated Colmar, France.

General Eisenhower ordered an extensive search, which finally discovered the safes six weeks later in a nearby river.