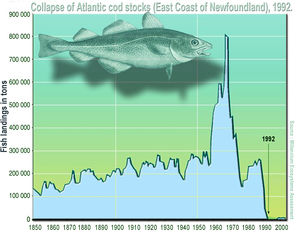

Collapse of the Atlantic northwest cod fishery

[4] A significant factor contributing to the depletion of the cod stocks off Newfoundland's shores was the introduction of equipment and technology that increased landed fish volume.

A significant factor contributing to the depletion of the cod stocks off the shores of Newfoundland included the introduction and proliferation of equipment and technology that increased the volume of landed fish.

[5] From the 1950s onwards, as was common in all industries, new technology was introduced that allowed fishers to trawl a larger area, fish deeper and for a longer time.

By the 1960s, powerful trawlers equipped with radar, electronic navigation systems, and sonar allowed crews to pursue fish with unparalleled success, and Canadian catches peaked in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Economically unimportant incidental catch undermines ecosystem stability, depleting stocks of important predator and prey species.

[8] This led to uncertainty of predictions about the "cod stock," making it difficult for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans in Canada to choose the appropriate course of action when the federal government's priorities were elsewhere.

[14] In 1976, the Canadian government declared the right to manage the fisheries in an exclusive economic zone that extended to 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) offshore.

It is essential, therefore, that various interest group conflicts be minimized and that the appropriate measures be taken to ensure that benefits accruing from the exploitation of fish stocks are consistent with rational resource management objectives and desirable socio-economic considerations.In 1986, scientists reviewed calculations and data, after which they determined, to conserve cod fishing, the total allowable catch rate had to be cut in half.

[19] Other factors for the slow recovery of the original life-history characteristics of cod include lower genetic heritable variation due to overexploitation.

These effects are reflected in Canadian folklorist and songwriter Shelley Posen's song "No More Fish, No Fishermen"[21] and the dire environmental impact of the moratorium was heavily covered in contemporary media at the time.

[22] The collapse of the northern cod fishery marked a profound change in the ecological, economic and socio-cultural structure of Atlantic Canada.

The moratorium in 1992 was the largest industrial closure in Canadian history,[23] and it was expressed most acutely in Newfoundland, whose continental shelf lay under the region most heavily fished.

[10] In response to dire warnings of social and economic consequences, the federal government initially provided income assistance through the Northern Cod Adjustment and Recovery Program, and later through the Atlantic Groundfish Strategy, which included money specifically for the retraining of those workers displaced by the closing of the fishery.

As the predatory groundfish population declined, a thriving invertebrates fishing industry emerged, snow crab and northern shrimp proliferated, providing the basis for a new initiative that is roughly equivalent in economic value to the cod fishery it replaced.

COSEWIC listed Atlantic cod as "vulnerable" (this category later renamed "special concern") on a single-unit basis, i.e. assuming a single homogeneous population.

The potential designation change (from Not At Risk to Endangered) was highly contentious because many considered that the collapse of Atlantic cod had ultimately resulted from mismanagement by DFO.

That is undoubtedly why, before the meeting which was to decide the designation, COSEWIC had massively unannouncedly edited the Report, thereby introducing many errors and changing meanings, including removing the word "few" from "there are few indications of improvement," and expunging a substantial section which engaged various objections raised by DFO.

[27] In 1998 in a book, Bell argued[38] that the collapse of the fishery and the failure of the Listing process was ultimately facilitated by secrecy (as long ago in the defense science context observed by the venerable C. P. Snow[39] and recently cast as "government information control" in the fishery context[40]) and the lack of a code of ethics appropriate to (at least) scientists whose findings are relevant to conservation and public resource management.

[43] Åsmund Bjordal, director of the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research, disputed the WWF's claim, noting the healthy Barents Sea cod population.

In 2015, the Norwegian Seafood Council invited Crown Prince Haakon to take part in opening the year's cod fishing season on the island of Senja.

[46] Local inshore fishermen blamed hundreds of factory trawlers, mainly from Eastern Europe, which started arriving soon after WWII, catching all the breeding cod.

In the Canadian system, however, under the 2002 Species at Risk Act (SARA)[47] the ultimate determination of conservation status (e.g., endangered) is a political, cabinet-level decision;[47] Cabinet decided not to accept COSEWIC's 2003 recommendations.

In 2004, the WWF in a report agreed that the Barents Sea cod fishery appeared to be healthy, but that the situation may not last due to illegal fishing, industrial development, and high quotas.

[48] In The End of the Line: How Overfishing Is Changing the World and What We Eat, author Charles Clover claims that cod is only one example of how the modern unsustainable fishing industry is destroying ocean ecosystems.

[49] In 2005, the WWF—Canada accused foreign and Canadian fishing vessels of deliberate large-scale violations of the restrictions on the Grand Banks, in the form of bycatch.

WWF also claimed poor enforcement by NAFO, an intergovernmental organization with a mandate to provide scientific fishery advice and management in the northwestern Atlantic.

In 2011 in a letter to Nature, a team of Canadian scientists reported that cod in the Scotian Shelf ecosystem off Canada showed signs of recovery.