Disaster preparedness (cultural property)

To plan for and prevent disasters from occurring, cultural heritage organisations will often perform a risk assessment to identify potential hazards and how they might be ameliorated.

From this they will develop a disaster (or emergency) response plan that is tailored to the needs of their institution, taking into consideration factors like climate, location, and specific collection vulnerabilities.

[2] In some countries and jurisdictions there may be official requirements for an emergency preparedness plan, quality assurance standards, or other guidelines determined by the government or local authorities.

Cultural property faces threats from a variety of sources on a daily basis, from thieves, vandals, and pests; to pollution, light, humidity, and temperature; to natural emergencies and physical forces.

Disaster preparedness strives to mitigate the occurrence of damage and deterioration through risk management, research and the implementation of procedures which enhance the safety of cultural heritage objects and collections.

A handling accident, where a single item is dropped and damaged, is also an example of physical forces but may not be considered a 'disaster' in the context of disaster planning as the incident likely can be dealt with as part of regular day-to-day business.

Examples of natural disasters include hurricanes, tornados, floods, blizzards, landslides, earthquakes and their aftershocks, bushfires or wildfires, and sandstorms or dust storms.

Some types of natural disasters are becoming more likely and more severe due to anthropogenic climate change, placing many cultural heritage sites at greater risk.

[12] Relative Humidity (RH) can cause damage to cultural heritage when it is too high, too low or fluctuates to widely or frequently for specific materials.

Physical forces that may result in collection disasters include earthquakes, structural collapse of buildings, and damage caused by civil unrest and war.

As examples, the Broadway Theatre Archive of 35,000 photographs was lost, as was one of the largest existing urban archaeological assemblages, that of the Five Points area in nineteenth century New York.

[18] Many churches were damaged or destroyed in these earthquakes, including paintings, frescoes, furniture, manuscripts, and stained glass windows contained within.

[22] The Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris suffered a devastating fire in April 2019 that damaged priceless artefacts and the magnificent roof structure.

[23] Flooding in locations that experience extreme weather conditions (rainfall, storms) is one relatively common type of disaster affecting cultural collections.

Extreme forms of dissociation (separation of the physical item from the information that makes it significant) might include a critical loss of electronic data that cannot be retrieved, or the closure or sale of the collection (in parts or in its entirety) due to financial or political pressures.

For example, serious issues can be created due to funding or sponsorship scandals; misuse of funds; the presence of looted cultural property or material acquired by unethical means; political or social perspectives on activities undertaken by the governing body, a donor, or even the institution's founder; and wider societal economic pressures leading to the closure of collecting organisations due to loss of income.

Political, business, social, religious or media pressure groups may in some cases interfere with the operation of cultural organisations, leading to selection bias, propaganda, discrimination or censorship attempts (e.g. in the presentation of exhibitions, or in recruitment processes).

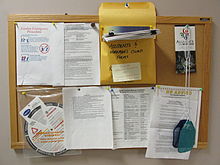

Other preparatory activities include creating and maintaining an inventory of the collection, identifying salvage priorities for different disaster scenarios, developing emergency telephone contact lists, identifying critical resources and contractors, and assembling useful disaster salvage equipment and supplies (e.g. spill kits, wet-dry vacuum cleaners, fans).

A policy may specify the replacement value of objects owned by the museum and those loaned by other organisations, and cover building repairs, temporary offsite storage, clean-up operations and other costs incurred.

Facilities management ensure gas, sewage, electricity and water services are well-maintained and compliant with local codes.

Collection management teams ensure items are stored in a manner to prevent water, dust and pest ingress.

Immediate action taken within the first few hours or days to stabilize the environment, assess the damage, and report conditions and recommendations may be considered the 'response' phase of the disaster.

Risk assessments are recommended to identify hazards to health and safety and to implement controls before recovery salvage work begins.

Plans developed during the response phase are put into action, and regularly reviewed and revised for as long as salvage operations continue.

Strategies to raise funds have included approaches to existing donors, 'adopt an artefact' campaigns where groups or individuals sponsor the conservation of damaged objects or exhibits, and fundraising events.