Collectivization in the Soviet Union

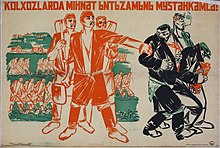

The policy aimed to integrate individual landholdings and labour into nominally collectively-controlled and openly or directly state-controlled farms: Kolkhozes and Sovkhozes accordingly.

When the Russian Civil War ended, the economy changed with the New Economic Policy (NEP) and specifically, with the replacement of prodrazvyorstka with less drastic prodnalog or "food tax."

Leon Trotsky and the Opposition bloc had advocated a programme of industrialization which also proposed agricultural cooperatives and the formation of collective farms on a voluntary basis.

[5] Other scholars have argued that the economic programme of Trotsky differed from the forced policy of collectivisation implemented by Stalin after 1928 due to the levels of brutality associated with its enforcement.

Although the income gap between wealthy and poor farmers did grow under the NEP, it remained quite small, but the Bolsheviks began to take aim at the kulaks, peasants with enough land and money to own several animals and hire a few labourers [citation needed].

Lenin claimed, "Small-scale production gives birth to capitalism and the bourgeoisie constantly, daily, hourly, with elemental force, and in vast proportions.

[16] Faced with the refusal to hand grain over, a decision was made at a plenary session of the Central Committee in November 1929 to embark on a nationwide program of collectivization.

As a form of protest, many peasants preferred to slaughter their animals for food rather than give them over to collective farms, which produced a major reduction in livestock.

[citation needed] The agricultural means of production (land, equipment, livestock) were to be totally "commonalised" ("обобществлены"), i.e. removed from the control of individual peasant households.

[citation needed] The zeal for collectivization was so high that the March 2, 1930, issue of Pravda contained Stalin's article Dizzy with Success (Russian: Головокружение от успехов, lit.

That means that by February 20, 1930, we had overfulfilled the five-year plan of collectivization by more than 100 per cent.... some of our comrades have become dizzy with success and for the moment have lost clearness of mind and sobriety of vision.

[citation needed] Later a number of authors suggested that this Stalin's article was picking scapegoats, putting the blame on rank-and-file functionaries for his own excesses and quenching the rising discontent.

[26] The oversimplified intent was to withhold grain from the market and increase the total crop and food supply via state collective farms, with the surplus funding future industrialization.

To make matters worse, tractors promised to the peasants could not be produced due to the poor policies in the Industrial sector of the Soviet Union.

Rumors circulated in the villages warning the rural residents that collectivization would bring disorder, hunger, famine, and the destruction of crops and livestock.

They "physically blocked the entrances to huts of peasants scheduled to be exiled as kulaks, forcibly took back socialized seed and livestock and led assaults on officials.

The subsequent recovery of the agricultural production was also impeded by the losses suffered by the Soviet Union during World War II and the severe drought of 1946.

Stolypin's program of resettlement granted a lot of land for immigrants from elsewhere in the empire, creating a large portion of well-off peasants and stimulating rapid agricultural development in the 1910s.

[70] Historian Sarah Cameron argues that while Stalin did not intend to starve Kazakhs, he saw some deaths as a necessary sacrifice to achieve the political and economic goals of the regime.

[72] Niccolò Pianciola goes further than Cameron and argues that from Lemkin's point of view on genocide all nomads of the Soviet Union were victims of the crime, not just the Kazakhs.

[73] Most historians agree that the disruption caused by collectivization and the resistance of the peasants significantly contributed to the Great Famine of 1932–1933, especially in Ukraine, a region famous for its rich soil (chernozem).

During the similar famines of 1921–1923, numerous campaigns – inside the country, as well as internationally – were held to raise money and food in support of the population of the affected regions.

[82] The center of the famine, however, was Ukraine and surrounding regions, including the Don, the Kuban, the Northern Caucasus and Kazakhstan where the toll was one million dead.

[83] In The Black Book of Communism, the authors claim that the number of deaths was at least 4 million, and they also characterize the Great Famine as "a genocide of the Ukrainian people".

[85][86] After the Soviet Occupation of Latvia in June 1940, the country's new rulers were faced with a problem: the agricultural reforms of the inter-war period had expanded individual holdings.

[citation needed] Latvians were accustomed to individual holdings (viensētas), which had existed even during serfdom, and for many farmers, the plots awarded to them by the interwar reforms were the first their families had ever owned.

[citation needed] Pressure from Moscow to collectivize continued and the authorities in Latvia sought to reduce the number of individual farmers (increasingly labelled kulaki or budži) through higher taxes and requisitioning of agricultural products for state use.

[citation needed] Rural life changed as farmers' daily movements were governed by plans, decisions, and quotas formulated elsewhere and delivered through an intermediate non-farming hierarchy.

During World War II, Alfred Rosenberg, in his capacity as the Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories, issued a series of posters announcing the end of the Soviet collective farms in areas of the USSR under German occupation.

[citation needed] By 1943, the German occupation authorities had converted 30% of the kolkhozes into German-sponsored "agricultural cooperatives", but as yet had made no conversions to private farms.