Heritability

[1] The concept of heritability can be expressed in the form of the following question: "What is the proportion of the variation in a given trait within a population that is not explained by the environment or random chance?

"[2] Other causes of measured variation in a trait are characterized as environmental factors, including observational error.

Therefore, its use conveys the incorrect impression that behavioral traits are "inherited" or specifically passed down through the genes.

Matters of heritability are complicated because genes may canalize a phenotype, making its expression almost inevitable in all occurring environments.

[12] Estimates of heritability use statistical analyses to help to identify the causes of differences between individuals.

This last point highlights the fact that heritability cannot take into account the effect of factors which are invariant in the population.

Factors may be invariant if they are absent and do not exist in the population, such as no one having access to a particular antibiotic, or because they are omnipresent, like if everyone is drinking coffee.

This reflects all the genetic contributions to a population's phenotypic variance including additive, dominant, and epistatic (multi-genic interactions), as well as maternal and paternal effects, where individuals are directly affected by their parents' phenotype, such as with milk production in mammals.

For traits which are not continuous but dichotomous such as an additional toe or certain diseases, the contribution of the various alleles can be considered to be a sum, which past a threshold, manifests itself as the trait, giving the liability threshold model in which heritability can be estimated and selection modeled.

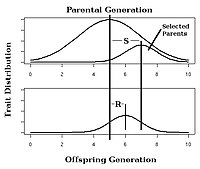

If a selective pressure such as improving livestock is exerted, the response of the trait is directly related to narrow-sense heritability.

The simplest genetic model involves a single locus with two alleles (b and B) affecting one quantitative phenotype.

Estimates of the total heritability of human traits assume the absence of epistasis, which has been called the "assumption of additivity".

[16] There is also some empirical evidence that the additivity assumption is frequently violated in behavior genetic studies of adolescent intelligence and academic achievement.

The statistical analyses required to estimate the genetic and environmental components of variance depend on the sample characteristics.

Briefly, better estimates are obtained using data from individuals with widely varying levels of genetic relationship - such as twins, siblings, parents and offspring, rather than from more distantly related (and therefore less similar) subjects.

For example, among farm animals it is easy to arrange for a bull to produce offspring from a large number of cows and to control environments.

Such experimental control is generally not possible when gathering human data, relying on naturally occurring relationships and environments.

A limit of this design is the common prenatal environment and the relatively low numbers of twins reared apart.

[19] A basic approach to heritability can be taken using full-Sib designs: comparing similarity between siblings who share both a biological mother and a father.

Unique environmental variance, e2, reflects the degree to which identical twins raised together are dissimilar, e2=1-r(MZ).

[14] Considering only the most basic of genetic models, we can look at the quantitative contribution of a single locus with genotype Gi as where

The expected mean square is calculated from the relationship of the individuals (progeny within a sire are all half-sibs, for example), and an understanding of intraclass correlations.

Other methods for calculating heritability use data from genome-wide association studies to estimate the influence on a trait by genetic factors, which is reflected by the rate and influence of putatively associated genetic loci (usually single-nucleotide polymorphisms) on the trait.

[23] When a large, complex pedigree or another aforementioned type of data is available, heritability and other quantitative genetic parameters can be estimated by restricted maximum likelihood (REML) or Bayesian methods.

This gives a genomic heritability estimate based on the variance captured by common genetic variants.

[4] There are multiple methods that make different adjustments for allele frequency and linkage disequilibrium.

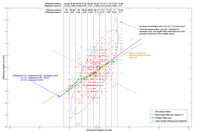

[14]: 1957 [26] For example, imagine that a plant breeder is involved in a selective breeding project with the aim of increasing the number of kernels per ear of corn.

Bentall has claimed that such heritability scores are typically calculated counterintuitively to derive numerically high scores, that heritability is misinterpreted as genetic determination, and that this alleged bias distracts from other factors that researches have found more causally important, such as childhood abuse causing later psychosis.

[29][30] Heritability estimates are also inherently limited because they do not convey any information regarding whether genes or environment play a larger role in the development of the trait under study.

[35] Eric Turkheimer has argued that newer molecular methods have vindicated the conventional interpretation of twin studies,[35] although it remains mostly unclear how to explain the relations between genes and behaviors.